My name is Moss... Stirling Moss

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- January 7, 2026

Related articles

- Stirling Moss - How Stirling got his Mercedes breakthrough, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Stirling Moss - Moss' Porsche days, part 1, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Stirling Moss - Moss' Porsche days, part 2, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Zandvoort - The quintessential GP track in the dunes, by Mattijs Diepraam

Who?Stirling Moss What?Cooper-J.A.P. MkIII Where?Zandvoort When?II Grote Prijs van Zandvoort (July 31, 1949) |

|

Why?

We are used to thinking about the great names in motorsport always from the perspective of their great victories and achievements: Michael Schumacher and his seven WDC titles in Formula One, Graham Hill and his conquest of the Triple Crown, or Henri Pescarolo and his four overall victories in the 24h of Le Mans. It is through moments like these and many other drivers, entered the annals of the sport, as legends who left their mark on the race tracks all around the world.

However, most people forget that the path to the top of the sports food chain is exhausting, and it leads to complete ostracism when the great successes begin to pile up alongside the medals and trophies. But a true race driver must never forget where he came from, and those first successes, when he was still treated as a mere unknown, only serve to reinforce the meaning of the entire career.

Being recognised as one of the great drivers of his time, Stirling Moss is always remembered for his greatest achievements. Despite the F1 title having slipped through his fingers on several occasions, 16 Grande Épreuve victories in the category, added to achievements in the Mille Miglia, Targa Florio and other traditional events on the international automobile calendar of the 50s and 60s give us an idea of Moss' size in the context of its time.

Although Moss's early years in motorsport are covered in hundreds of reports and biographies, which focus almost exclusively on his leap from the British national categories to international stardom (i.e. the exact year 1950), few give due credit to the driver in his days as a newcomer to the sport, and how Moss in the bubbling post-WW2 motorsport scene managed to stand out.

The poster of the 1949 Grote Prijs von Zandvoort

Certainly, one of the most important and ignored milestones in Moss' beginnings was his first international victory in single-seater racing, achieved in a modest support event for the 1949 Zandvoort Grand Prix. While Moss would present a gala performance in the meeting's Formula 3 race, one wonders how many of the F1 drivers who watched the race from the pits or the stands waiting for their turn to dominate the Zandvoort circuit, expected that that young British driver would become one of their fiercest rivals in the years to come...

That race in July 1949 would prove to be one of the great turning points in Moss's career; But to see this, we must go back in time, when one of the greats of motorsport took his first step towards the journey of his life.

Moss: building a reputation

Stirling Moss was born in 1929, in Bayswater, in the middle of the triangle formed by the neighbourhoods of Notting Hill, Kensington and Paddington, in West London. Despite his urban roots, Moss practically lived his entire youth on the outskirts of the British capital, mainly on his family's farm in Surrey. Early on, Moss demonstrated a tendency towards sport, practicing boxing, swimming, horse riding and rugby.

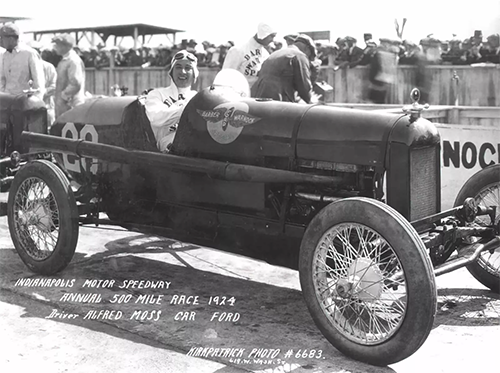

However, another passion that Stirling cultivated from an early age was that related to mechanics and speed. In addition to living in a rural environment, where the automobile had taken over from the horse as the main tool for moving goods and people, it was said that motorsports ran inherently in the veins of the Moss family. Stirling's father, Alfred, had been a semi-professional driver in the mid-1920s, having as his great milestone being the first British driver to compete in the Indianapolis 500 (1924); while his mother, Aileen, had also been an amateur driver, competing in various rallies and cross-country races in the British Isles during the same era.

Although the couple slowed down in their automotive 'adventures' after the birth of Stirling and his sister, Pat, both Alfred and Aileen never truly neglected their ties with the sport. The story goes that Alfred took a 5-year-old Stirling for his first lap around the Brooklands circuit, and that Stirling already knew how to drive a vehicle at the age of 10!

Speed ran in the Moss family's blood. Here we see father Alfred, at the greatest moment of his life as a driver, during the 1924 Indianapolis 500. (credits Chevrolet Brothers)

Going forward a few years, we arrive at 1947. The war had come and gone, leaving a trail of destruction and scars that would take time to heal. The world of the second half of the 40s did not resemble the one in which the young Stirling Moss had grown up – it was a time of changes, which affected the whole of society. Motorsport did not escape this rule, as the ashes of Europe were cleaned from the circuits across all corners of the continent.

This would be Stirling's second great moment of interaction with motorsport. Now 18, the teenager saw himself in a position to join the movement to restructure the race events after the break that devastated the sport between 1939-'45. This rapprochement between Moss and vehicles occurred at the same time as major motorsport changes were happening, and which had as epicenter England itself, the main one being the birth of the 500cc formula, which would later become known as the first incarnation of modern F3.

The history of the 500cc formula actually dates back to the late 1930s when a group of amateur drivers from Bristol, who would later become known as CAPA, decided to build a limited series of single-seaters vehicles, with the intention of competing in small club meetings held at the local racetrack.

With a very lean budget, what this group wanted was what almost every amateur driver is looking for: a low-cost, high-performance category which did not require a large commitment of time and resources to have a competitive vehicle as the final product. The solution found to this dilemma was the combination of cheap and abundant chassis, like those of British-built Austin Sevens and Model T Fords, with motorcycle engines, especially 500cc Nortons, much more economical than those which equipped the cars of the time.

The combination proved incredibly successful in the short time it could be applied, with global conflict putting a brake on this promising development. Fortunately, the vehicles and the idea of the 500cc formula made it through the conflict almost unscathed, being immediately reintroduced into the British motorsport scenario as soon as the war became a memory.

The 500cc formula proposal (also known at that time as Class I) seemed to be a flawless concept, and, obviously, it didn't take long for it to start spreading across England. Well-known motorsport venues in the British Isles, such as Shelsley Walsh and Prescott, were the first places outside Bristol to accept 500cc single-seaters on their entry lists, as early as 1946. The 500cc cars, which were soon unified under the Class I regulations at the end of the 40s, quickly began to evolve in design, incorporating new features that also affected other international motorsport categories. It didn't take long for the 'poor man's racing car', as these first generation 500cc formula cars would become known, to give way to increasingly refined, and consequently, expensive designs.

One of the most important milestones in the evolution of Class I vehicles, right at the time when Moss was taking his first steps in the category, was its regulation by the British Automobile Racing Club (BARC), since, until now, much of the control of the category was in the hands of the Bristol Airplane Company Motor Sports Club (BACMSC), the birthplace of Class I/F3. The appearance of the BARC allowed a leap forward in the category, which now left its micro-regional roots to officially characterise itself as a national category.

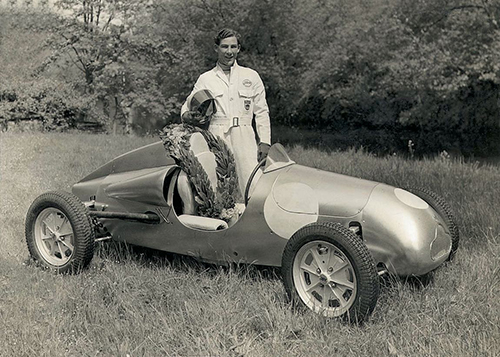

Moss next to his brand new MkIII. It was with this car that Stirling hoped to shine in 1949. (credits BMW AG)

Stirling's first attempt to participate in the fledgling F3 took place in 1947, when Moss, still 17 years old, tried to buy a Marwyn, one of the first 500cc cars produced in scale. Stirling, recently graduated and discharged after his service as an army messenger, was a young man like so many others: broke, but with great ambition. For this reason, Moss gathered all the funds he had, sending Marwyn/MHW a check with a down payment of £50. Stirling's ruse was quickly discovered by his parents, who soon tried to request reimbursement for the amount sent by young Moss. But this was just a momentary setback in Stirling's life, because on his 18th birthday, he finally received the object he wanted most: his first racing car.

The vehicle in question was a sleek ladder-framed car, the first production model from an unknown Surbiton firm which would go down in history in the following decades: the Cooper Car Company. Named Mark II T5, the model was an evolution of the T2 and T3 prototypes, and presented a completely new car within the F3 scenario: if previously most vehicles in the category were built over the chassis and parts of salvaged street cars, the MkII T5 was basically built from scratch, with the exception of some mechanical parts, which, due to regulations, had to originate from production vehicles.

Only 12 MkII T5s were manufactured, and those lucky enough to get their hands on these vehicles between 1948-'49 enjoyed an extremely fertile period in terms of victories and achievements. Luckily Alfred, Stirling's father, still had contacts within the car industry at the time, which allowed the Moss family to be one of the first customers of this revolutionary machine.

The first challenges

As soon as the car was delivered, the wheels that would put Moss into British motorsport soon began to be set in motion: Alfred got in touch with Stan Greening, a long-time friend of the family and who was the main figure behind the J.A.P. engines, to see if Stan could give the machine a special 'touch' before it entered the competitive circle. Soon after, Alfred recruited the first official member of Stirling's team: the German Don Müller, a former BMW employee who now worked as a mechanic and farmer for the Moss family.

Those were busy days for the Moss family, especially for Alfred and Stirling, who were looking for an opportunity to attest not only the car's qualities, but mainly, those of the young Moss. This came on 9 May 1948, at the traditional Prescott Hill Climb, when Stirling for the first time had the chance to put his talents to the test in a real competitive scenario. Competing with nine other drivers for victory in the half-litre class, Moss managed to get fourth position – an excellent result for his first adventure in motorsport.

Less than a month later, Stirling got his second chance to prove what he was capable of: the Moss team entered the Cooper in the Brighton International Hill Climb, held in Stanmer Park. This time, young Moss did not let the opportunity escape him and, at the end of the event, Stirling left Brighton with the 500cc category winner's trophy, beating drivers such as Eric Brandon and Sir Francis Samuelson, some of the most seasoned in the British Isles at the time.

After this victory in Brighton, the eyes of the press began to focus on the hitherto unknown driver from Surrey. Victory in the next event, in the N.E. 500cc Scratch and Handicap Race at Brough (4th July), served to give more impetus in Stirling's journey to fame – as already in his first race on a closed circuit, Moss overcame much more senior drivers to take home his second trophy.

In addition to the victories above, Stirling would also collect the following triumphs in 1948: Bouley Bay 500cc Race (15 July); Prescott Hill Climb (July 18); Great Auclum Sprint (July 24); Boscombe Sprint Trials (7 August); Goodwood Trophy/500cc support event (18 September); Shelsley Walsh Hill Climb (25 September); and the 500cc Dunholme Lodge Meeting (9 October). Despite the victories accumulating on Stirling's CV, the primary objective for 1948 was the driver's consolidation on the British automobile scene.

Stirling Moss drives his Cooper MKII during the support event for the 1948 British GP.

(credits Reddit, photo colorised by the author)

The most important point for this goal was Stirling's participation in a support event for the 1948 British Grand Prix, in front of an illustrious audience that included more than 100,000 spectators, and drivers of the caliber of Villoresi, Ascari and Rosier. Although the race did not present the young Moss a victory (with a chain on his Cooper breaking a few laps before the end of the race, while Stirling was leading the race), the main objective had been achieved: a good impression had been left on the owners of the big teams and Scuderias, showing that the young driver had a huge future ahead of him.

The extremely positive outcome of 1948 had dispelled any doubts that remained in the Moss family about Stirling's potential. As a reward for his efforts, Alfred had helped Stirling, in early 1949, purchase the most up-to-date model offered by Cooper, the MkIII. With just a few imperceptible aerodynamic refinements, the MkIII was practically a copy of the MkII in its most basic version, known as the T7. However, Stirling chose to purchase the more expensive and special version of the model, known as the T9.

The big difference between the T7 and T9 models was that the latter allowed quick engine swaps, with the car being able to accommodate not only the traditional J.A.P. or Norton 500cc powerplants suited for F3, but also 1000cc ones which were eligible in some Formula 2/F Libre races. This was due to an extension of the T9 chassis, in addition to an ingenious lock and unlock system developed for easy engine swaps – something that was not present in the more conventional T7.

For 1949, the driver hoped to participate in his first 'international tour' that would take place between the months of June and July. However, before this could happen, Stirling wanted to 'soften his new machine' and entered the MkIII in the most popular and hotly contested Class I events in the first half of the year: the Goodwood Easter Meeting, where Moss finished in a modest 10th place, and in the support event (500cc class) of the 1949 British GP, when Moss finally grabbed the win after it had slipped through his fingers in 1948. (Note: Moss would also take another victory during this period, in a small 500cc Formula meeting in Blanford in May.)

One of the rare photos of Moss's debut in continental Europe, during the 1949 IX Circuito del Garda. (credits AISA)

Foreshadowing his journey through the countries of continental Europe, Stirling decided to do his first international trial much closer to home, in a joint F2/F Libre race on the Isle of Man. On 25 May, racing his Cooper powered by a 1000cc J.A.P., Moss finished 11th in the III Manx Cup, due to a problem with the magneto in the last laps. Despite having shown interest in participating in the traditional Grand Prix des Frontières (Chimay) at the beginning of June, Stirling decided to skip that leg, delaying his debut on continental soil until July. His first challenge then would be at the foothills of the Italian Alps at the IX Circuito del Garda.

Suffering strong opposition from Scuderia Ferrari and Cisitalia, Moss managed to secure a massive third place, only behind the works-166Cs of Villoresi and Tadini. A week later, Stirling was back in action, this time in Reims at the III Coupe des Petites Cylindrées – a ninth place in the race was celebrated with some euphoria, mainly due to the adverse conditions that Stirling had to face in the meeting. However, it is worth remembering that the III C.P.C. was a support category for the main event at Reims that weekend, F1. Thus, Moss was closer than ever to the category and its stars, as he would follow the F1/F3 circus to their next joint stop: Zandvoort.

A boy of Surrey in the dunes of Zandvoort

A factor that had strongly affected Moss's performance in the events at Garda and Reims would luckily not be present in Zandvoort: the presence of factory-backed squads, which were disproportionately better prepared than the simple effort of that young man and his garagiste team from Surrey. In the Italian race, the big challenge was the trio of Ferraris of Villoresi, Tadini and Sterzi, which would certainly have taken the three podium positions if it weren't for a serious accident suffered by Sterzi during the race.

At Reims, the situation was even more difficult: in addition to the works-166Cs of Ascari, Tadini, Fangio and Froilán González, Ecurie Gordini also dispatched its delegation of T15 models for Trintignant, Manzon and Sommer, besides HW Motors (commonly known as HWM) with its Alta-engined model for John Heath. Despite Moss's Cooper being lighter than all its rivals, the T9 didn't stand a chance due to its F2-spec 1000cc engine; in comparison, the Gordinis were equipped with 1460cc engines and the Ferraris with 1496cc ones.

But the support event that Moss glimpsed to participate at Zandvoort would be qualified as a Class I race (or Formula 3, to facilitate nomenclature), which forbade the entry of such machines. Thus, this would be a clear dispute between the different models of the 500cc formula, with special emphasis on the Cooper chassis.

Although this was not the first official Class I race in continental Europe (with several small events having taken place mainly in Sweden, Germany and Belgium), the event in Zandvoort would be pioneering in the sense of being the first to take place in partnership with a major event which would be the Zandvoort GP for Grand Prix cars. The small F3 cars would open the show, which would feature a handful of other attractions, and whose pinnacle would be the Ferraris, ERAs, Maseratis and Talbots of the great motorsport aces of the time.

As it had been at Reims and in the two British GP support events he had participated in, this was a golden opportunity for Moss to stand out in the eyes of those who could propel his professional career to the next level. But to do so, Stirling would have to face strong competition, which amounted to ten other drivers on the F3 race grid. Most of them were already known to Moss, as fellow Class I competitors on British soil: no less than ten (including Stirling) of the 11 drivers who would participate in the race were English, with the exception of Dutchman Lex Beels.

Furthermore, Stirling knew that he would need patience and nerves to overcome some of his rivals: Eric Brandon, co-founder of the Cooper Car Company and also one of the most experienced drivers in F3 at that time; Ron 'Curly' Dryden, who, through a string of excellent results, became one of Moss's main rivals in the 1949 season; Don Parker, one of the most eccentric figures in the category; in addition to Sir Francis Samuelson, who, at the age of 59 (!), was one of the fastest drivers in Formula 3.

Who also deserves his due attention is an unknown Peter Collins who like Moss would be destined for a brilliant future in the decade to come. There was still hope that John Cooper could attend the race, driving one of his own creations, but due to an unforeseen event the half-businessman, half-driver had to decline the invitation at the last moment.

Almost all of these (and the other drivers who gave final numbers to the grid) were equipped with Coopers, of the MkII and MkIII models. But as always, there were exceptions: Don Parker had taken his Parker '500' to Holland, a unique model built by the driver himself and equipped with a J.A.P. engine. Charlie Smith, another British driver, also headed to Zandvoort with a model of its own production, the CFS – which was also thrusted by a J.A.P. powerplant.

Moss follows the flow of the curve, as he distances himself from the rest of the field during the race in the Netherlands,

in 1949. (credits unknown, colorised by the author)

With the entry list closed, the drivers began to converge on the picturesque Zandvoort circuit, located among the dunes on the edge of the North Sea. Opened just a year prior, Zandvoort could still be considered a primitive venue at the time if compared to other European circuits. Much of the track was built with remains and scraps from the Second World War, in particular, materials scavenged from the pre-war resort that existed on the site, and which had been partially demolished to make way for fortifications of the well-known Nazi Atlantic Wall.

Asphalt of dubious quality was combined with sand from the dunes to transform the surface into an emery, consuming the tyres at an extremely alarming rate. Even so, such flaws in no way diminished the Zandvoort circuit and facilities, which quickly gained a positive reputation among drivers and the crowd: the challenging and fluid layout was very different from that seen in other European circuits, while due to its natural geography surrounded by dunes, the track offered several vantage points with excellent fields of vision, which gained credit among the spectators.

In the days preceding the race, the drivers had the opportunity to explore the circuit: despite the little time that the F3 drivers had (obviously due to the preference the GP cars had in the weekend), every second was important, since almost no one knew the track. Neither did Moss, who on his first international trip was racing on a virtually unknown circuit.

While Stirling explored the 4,193-meter route for the first time, some of his rivals took the opportunity to make their own adjustments: Eric Brandon was forced to change the engine of his Cooper, after his original J.A.P. showed little in the fast laps performed by him. Home driver Lex Beels also had his share of problems: despite being quite familiar with the challenges of Zandvoort (having already competed in half a dozen events on the location) this was the first time that the Dutchman had taken his Cooper to the track – having received it just 12 days prior!

Despite the small advantages or setbacks that one or another driver could have, it was no exaggeration to say that the 500cc formula field competed on equal terms for pole position. It was the quality of the man behind the wheel that would be the determining factor at this stage. And so, the result materialised, with Moss once again confirming the expectations placed on his shoulders.

It was the boy from Surrey who secured pole position, sharing the front row with John Harbin (Cooper MkIII) and Eric Brandon (Cooper MkIII); right behind, in the second row, were 'Curly' Dryden (Cooper MkII) and Don Parker (Parker '500'); the third row was made up of Bill Aston (Cooper MkIII), Peter Collins (Cooper MkIII) and Stan Coldham (Cooper MkIII); next came Lex Beels (Cooper MkIII) and Charlie Smith (CFS); and, closing the field, alone, on the last row, Sir Francis Samuelson (Cooper MkII).

Race day had an unpleasant surprise in store for the drivers: if Saturday's practice sessions were carried out in sunshine and mild weather, Sunday was all but the opposite. The unpredictability of the weather at the North Sea had played another trick, and it was up to the drivers to deal as best as possible with the rain and gusts of wind that plagued the Zandvoort circuit throughout the morning of the 31st.

The luck of the drivers in the 500cc category is that they would not be the first to enter the track, with two heats for GP cars opening the day's agenda for the Grote Prijs van Zandvoort. So, when the Class I/F3 cars were finally released to take their starting positions, at least the track was already in minimally better conditions than that faced by the drivers in the first races.

It was just after 2pm when the flag was waved to Moss & co. And right at the start, a tragi-comical moment: one of Harbin's mechanics was still making the final adjustments to his boss's car when the starting authorisation was given – and he, in a state of desperation, tried to run towards the pits! Obviously, the fastest route between two points is a straight, which in this case went through in front of Moss' car.

So, in the reflex of trying to reach to the pits as quickly as possible, the mechanic didn't notice Moss' almost instantaneous reaction to the start, with the mechanic being caught squarely by Stirling's Cooper. In a Dantesque and comical scene, the mechanic ended up upside down in the car's cockpit, with both Moss and the mechanic sandwiched in the MkIII's tiny cockpit. Luckily, Stirling was unharmed by the accident, only losing some seconds in the race. Harbin's mechanic also escaped more serious injuries, with only scratches and cuts on his arms and head.

Stirling Moss hits John Harbin's mechanic at the start of the 1949 race. A comical moment,

which almost turned into tragedy. (credits GP Library)

While Moss suffered this setback, some drivers capitalised on the situation: Eric Brandon, John Harbin and 'Curly' Dryden managed to overtake Stirling, as the Surrey driver stabilised in fourth, with Don Parker and Bill Aston close behind. But this situation did not last long, as Moss quickly recovered from his incident at the start: at the end of the first lap, Stirling was up into second, having overtaken both Harbin and Dryden. While Brandon and Moss were fighting for the lead from the second lap onwards, some other drivers began to have problems: Don Parker, in the Parker '500', abandoned the race due to ignition problems, while Charlie Smith also suffered from bad luck, with his engine breaking down after just two laps.

Returning to the front of the field, Stirling focused on closing the gap between himself and Eric Brandon, with the two Coopers quickly circling around the Dutch circuit. At the beginning of the third lap, Moss was already on the tail of Brandon, who couldn't do much when Stirling made his move to take the first spot. The lead changed hands, with young Moss leading a race in continental Europe for the first time. And it wasn't long before the young driver from Surrey began to put his own stamp on the race, with the possibility of a counter attack from Brandon diminishing at every turn.

While the battle for the lead cooled down, other events in the midfield began to attract greater public attention: Peter Collins, at the end of the third lap, had problems with one of his engine's valves, being forced to take a long stop to its replacement. Soon afterwards, it was Francis Samuelson's turn to visit the pits, due to an engine breakdown.

These problems offered opportunities for surprises to shine: the main one was Lex Beels, who, after starting in ninth position, was already up into fifth at the halfway mark of the race. The driver gained another position on lap 6, when Harbin was forced to stop in the pits, also due to mechanical problems. At this time, Beels was gradually closing in on Bill Aston (in third), who in turn was attacking Eric Brandon.

Aston remained behind Brandon until lap 8, when he finally decided to unleash his attack. A beautiful move promoted Aston to second place while Brandon planned his counter attack, which in the end proved to be a failure. The duel between the two drivers served mainly to bring Beels closer, who was now harassing Brandon. Once again the latter failed to resist the pressure, and on lap 9, to the delight of the Dutch crowd, Beels was in third, with one foot on the podium.

Stirling Moss watched this clash from his mirrors, with a calmness that was previously unknown to the British drivers. Moss tried to be a little conservative in the final laps, perhaps a reflection of the reliability problems the driver had in some past 500cc events. But the gap was too large for his rivals to close, and at the end of tien laps and 23m21.200, Stirling took the chequered flag to guarantee his first international victory in single-seater racing.

A few seconds passed before Bill Aston, Lex Beels and Eric Brandon crossed the finish line, in the order described above. Just three tenths of a second separated Aston, Beels and Brandon, with the latter missing out on the podium by a minimal difference of one tenth to the Dutchman. Certainly, in its first major international test, the 500cc formula demonstrated what it was capable of, providing the crowd with accessible, unpredictable and extremely interesting entertainment.

Despite the confirmation of Moss's first continental victory, little visibility would be given to this achievement, as F3 was not the main attraction of that weekend at Zandvoort, serving only as a support event. As soon as the Class I cars were removed from the scene, it was the turn of the GP cars to resume their dominance for the final race of the 1949 Zandvoort GP. In the end, with names like Villoresi, Ascari, Farina and Sommer present, why give the highlights to an unknown teenager from the English countryside?

Just a prologue in a bigger picture

After the Zandvoort event, Stirling Moss would return to England to compete in the Silverstone 50-mile Race at the end of August, in which he would finish second behind Eric Brandon. Although this return apparently signalled the end of Stirling's foreign adventures in 1949, the driver apparently decided to take a step back from this decision, signing up for the II Prix de Léman, which was to be contested at the beginning of September.

The race, held in the suburbs of Lausanne (Switzerland) was another difficult test for Moss, who once again endured strong opposition from the works Ferrari, Gordini and HWM entries. Mechanical problems on lap 20 forced Stirling to withdraw from the race – which was certainly not the result sought by the driver in his last international meeting of 1949.

Despite the setbacks, Stirling had once again managed to achieve his main objectives for the year – in the same way as he had done in 1948. Following the circle of the leading drivers of the time at Silverstone, Reims and Zandvoort, Moss now became a more familiar face in the paddocks, and a name at least recognised in his native England.

For 1950, more ambitious objectives were put on the table, as the first breath of professionalisation of post-WW2 motorsport blew through Europe, with the establishment of the World Drivers Championship and a system of support categories recognised by the FIA, such as Formula Two and Formula Three. With the absorption of Class I into F3, Moss was at the right time and place to see his career really take off, as Europe finally embraced the 500cc formula.

Victory in the very first F3 event in Monaco (as a support event for the official GP) would be Moss's greatest achievement in 1950, serving as a springboard for the driver’s next step in his journey towards stardom: the signing of his first professional contract with an established team, HW Motors Ltd., which would enter Stirling in a handful of F2/F Libre races throughout 1950, with excellent results.

Thus began the journey of one of the greats in the history of motorsport, who over the next 12 years would build a legacy that would serve as the inspiration for generations of drivers to come. The important thing to remember is that all of this began in Zandvoort, on a summer day in 1949.