The second lost generation from Italy

Author

- Mattijs Diepraam

Date

- September 3, 2009

Related articles

- 1966 Italian GP - Ferrari's sportscar drivers walk the Park, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Giancarlo Baghetti - A bright light that faded quickly, by Felix Muelas/Mattijs Diepraam/Michael Ferner

- Jean-Pierre Beltoise - That rainy day in Monaco, by Mattijs Diepraam/Matej Muraus

- Eugenio Castellotti - The dashing Milanese that stayed young forever, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Scuderia Centro Sud - Italy's Maserati privateer, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Mike Parkes & Jonathan Williams - Brits and their Ferrari breaks, by Mattijs Diepraam

- John Surtees - A natural on two and four wheels, by Mattijs Diepraam

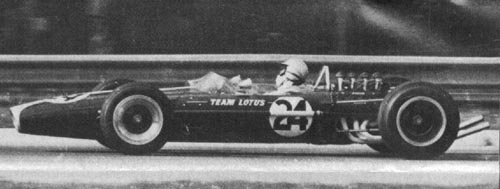

Who?Lorenzo Bandini What?Ferrari 312 Where?Monte Carlo When?XXV Monaco GP (May 7, 1967) |

|

Why?

When Giancarlo Fisichella was confirmed to replace Luca Badoer at Ferrari as a sub for Felipe Massa, the fact that an Italian is racing a Ferrari again was probably doubly haunting the older tifosi, well aware as they are of the once widespread belief that the concept is jinxed. Since the seventies, roughly speaking, the Scuderia scrutinously passed by any talented Italian – from Patrese to De Angelis, from Modena to Caffi – in favour of the cool and collected Germanic type of driver – from Lauda to Scheckter, from Prost to Schumacher – or drivers with Italian hearts instead of passports – Regazzoni, Villeneuve, Alesi.

It’s hard to judge the occasional Italian test driver jumping in at short notice although Galli, Larini and Morbidelli seem to have done solid jobs – better than Badoer, at least – but when Ferrari did sign an Italian driver for the full season they picked the wrong guys. Arturo Merzario was a fine sportscar driver but failed in F1 while Ivan Capelli was completely overwhelmed by the Ferrari experience. There is one exception to the rule, of course. Michele Alboreto joined in the mid-eighties to become a mainstay of the team but he remained the only successful Italian driver at Ferrari in a very long time, and raced in a period when Williams and McLaren were sharing the titles among themselves, meaning that Alberto Ascari is still the only Italian to have won a World Drivers Championship in a Ferrari.

It all goes back to two talented Italian generations being nibbed in the bud by Ferrari cars. In the fifties, Italy pinned its hopes on young Castellotti and Musso, but both were killed driving the Commendatore’s red cars. Staying away from Italian drivers for some time, the team finally tried again in the early sixties when Enzo Ferrari decided to support the talent promotion scheme set up by his confidant Eugenio Dragoni to reward an upcoming Italian driver with a Ferrari F1 car. This would be run by Dragoni's Scuderia Sant’Ambroeus on behalf of the Federazione Italiana di Scuderie Automobilistiche (FISA), a collective of Italian racing teams comprising the scuderie of Dolomiti, de Tomaso, Pescara, Settecoli, Montegrappa, Serenissima and Sant'Ambroeus. Initially, Dragoni picked his friend Giancarlo Baghetti for the seat – Giancarlo having won the Formula Junior Coppa FISA shoot-out at Monza on December 11, 1960 – and it looked like a dream scenario when Baghetti won his first three Grands Prix. His success meant that he was poised for a 1962 works seat, no doubt helped by the fact that Dragoni took over as team manager from ATS-bound Romolo Tavoni. However, the exodus of staff led by Tavoni and Chiti on the back of a failed ultimatum to Ferrari – your wife or us! – caused the Ferrari Grand Prix challenge to fall to dismal depths by the end of the year. And when Baghetti decided to join the renegades at ATS for 1963 he effectively killed off his GP career.

Giancarlo Baghetti slipstreams past Dan Gurney to take a sensational victory at Reims in 1961.

Baghetti wasn’t the only Italian at Ferrari in 1962, since Ferrari had brought in Lorenzo Bandini, the man of whom many suspected to have been the best pick for the FISA seat all along. Along with Baghetti and the other youngsters in the team – Ricardo Rodriguez and ‘Wild’ Willy Mairesse – Bandini was put on a rotating scheme, the four of them filling up to three seats next to team leader and reigning champion Phil Hill. Lorenzo had already had his GP baptism the year before when he joined Scuderia Centro Sud for four unhappy World Championship events in a Cooper-Maserati T53. At Spa, he had a wheel bearing fail while his engine blew at the Nürburgring. He soldiered on to 12th at Aintree and rose to 8th at Monza due to the high attrition rate, sandwiched by Carel de Beaufort’s Porsche and Maurice Trintignant’s Serenissima-run Cooper-Maser. It was quite a contrast to the highs that Baghetti at the time was living – but Lorenzo had a win in the Pescara 4 Hours to compensate for, sharing a 250TR with Scarlatti.

Bandini had been born in the Italian colony of Abessinia (now Lybia) and moved back from the African continent to Italy on the age of three. There, his father was abducted and murdered in the late stages of the war, leaving Lorenzo with the prospect of a very difficult childhood. Things changed when he became an apprentice in signor Freddi’s workshop in Milan and fell in love with the boss’s daughter, Margherita Freddi. The two eventually married in 1963, long after his employer and future father-in-law gave Lorenzo a Lancia Appia Zagato to race in the 1958 Mille Miglia. On the back of some outings in 1957 on board a borrowed Fiat 1100 he drove his Appia to a fine class win in the epic event. Switching to single-seaters in 1959, he raced a Scuderia Madunini-run Volpini in Formula Junior and did well enough to start his own garage business. A fourth in the Grand Prix-supporting FJ race at Monaco was his most noted result, combined with late-season wins in the Innsbruck Flugplatzrennen and the Coppa Madunina at Monza, now having moved to the team’s Stanguellini chassis. Staying with the Stanguellini in 1960, he won the 10th Prova Addestrativa. Lorenzo started off 1961 by beating the similar Stanguellini of FJ king and former team mate ‘Geki’ in the first Coppa Junior at Monza. This probably caught the eye of Scuderia Centro Sud’s Mimmo Dei who put him in his Lotus 20 for the Lotteria GP at Monza. Bandini finished second in the first heat but failed to convert this into anything substantial in the final. Still, this and a second place to Siffert at Enna was enough for signor Dei to give Lorenzo a Grand Prix opportunity.

Four GPs for Centro Sud at the back was quite something else compared to being a Ferrari driver at Monaco in 1962. Helped by the first-corner carnage and Lotus fragility Lorenzo hauled himself up to third, having repassed Surtees’s Lola in the closing stages. Not bad for a start! But while the Ferraris could still live with the British phalanx early in the season the gap steadily grew over the year, and the Italian cars were nowhere come season’s end. Bandini made two more World Championship appearances in 1962, at the Nürburgring and at Monza, but neither of them yielded any reward, as Ferrari trailed home a disconsolate sixth in the constructors’ championship. In between, Bandini did win the Mediterrenean GP at Enna-Pergusa. Furthermore, sharing a Dino with Baghetti, Lorenzo finished second in the Targa Florio earlier in the year, led by team mates Mairesse, Rodriguez and Gendebien. And of course, the Hill/Gendebien victory at Le Mans made up for quite a lot of Ferrari’s 1962 Grand Prix heartache.

Scuderia Centro Sud fielded a semi-works BRM P57 for Lorenzo Bandini in the early part of 1963.

Reconstructing for 1963, Ferrari signed John Surtees and focused its efforts on a two-car team. At Spa, Ferrari’s fast but accident-prone second driver Mairesse was involved in a huge accident while fighting Trevor Taylor over second place. While Willy was recovering from serious injury, the Belgian was replaced by yet another Italian about to make his GP debut for Ferrari. People were now beginning to get used to the idea of Italian drivers at Ferrari again, and significantly, Ludovico Scarfiotti wasn’t just the ordinary Italian driver – he was the nephew of Gianni Agnelli, who would be FIAT’s new boss in 1966 and would always take a keen interest in the F1 activities of the company FIAT gradually took over from 1965.

An accomplished hillclimber, Ludovico had shone for Ferrari in the European Mountain Championship, taking the 1962 title with a Dino sportscar. When he took over from Mairesse he had also just won the Le Mans 24 Hours, sharing a Ferrari 250P with that other young Italian Ferrari driver, Lorenzo Bandini, while earlier in the year he shared a similar car with John Surtees on their way to a win at Sebring. With Bandini again, he also finished second in the Targa Florio, only losing out to the Bonnier/Abate Porsche. Scarfiotti did well to score a point on his World Championship Grand Prix debut but a week later he crashed at Reims during practice for the French GP, suffering leg injuries. Mairesse was back in Germany – where Surtees won his first GP after Clark’s engine turned sour – but Willy’s smash at Spa had left its mark. When the mentally fragile Belgian crashed out of seventh place on the second lap, Bandini was brought back over from the sportscar team to join the Grand Prix team at Monza – no doubt helped by the fact that he put Centro Sud’s semi-works BRM on the front row at the ‘Ring! But even though ‘Big John’ took pole at Monza, with Bandini a creditable sixth on the grid, the results weren’t forthcoming. Surtees suffered one engine failure after the other in the remaining races while Lorenzo could only manage two very distant fifths. As in 1962, Bandini’s only joys would come from sportscar racing but one can imagine that his Le Mans win made up for several lost seasons at once! He also won the Trophée de l’Auvergne in Abate’s private Testa Rossa.

There would be more sportscar domination by Ferrari in 1964. At Sebring, Bandini and his F1 team mate Surtees brought up the rear of a Ferrari one-two-three, with Parkes/Maglioli taking the spoils ahead of Scarfiotti/Vaccarella. Bandini was third again in the Spa 500km, this time racing Filipinetti’s 250 GTO to join a Ferrari privateer one-two-three, but while Scarfiotti and Vaccarella matched up to win the Nürburgring 1000kms in the 275P, Surtees and Bandini had to give up after losing a wheel. Le Mans was a Ferrari whitewash as well. Surtees/Bandini took third with their 330P, led by Guichet/Vaccarella in the older 275P and Hill/Bonnier in the British 330P. The same pairing also won at Reims, beating Surtees/Bandini and Parkes/Scarfiotti. Meanwhile, Scarfiotti continued on his hillclimbing exploits, winning the Sierra Montagna amongst others, and was given a third Grand Prix Ferrari at Monza.

With another victorious Le Mans behind its belt Ferrari began to shift its efforts towards the Grand Prix team and this time it was starting to show. At the Nürburgring, Surtees finally won again for Ferrari and this time the breakthrough win was backed up by a hugely popular debut victory for Lorenzo on the dreary airfield circuit of Zeltweg, after he'd already taken third at the ‘Ring. Granted, the race had seen Dan Gurney and Jim Clark drop out from the lead while Graham Hill and Surtees also fell by the wayside, but Lorenzo had been a steady third and second throughout, thoroughly deserving the win. He took third again when Surtees won at Monza, the Brit now gathering enough points to mount a serious title challenge. Even the row that Enzo Ferrari started against the ACI for their lack of support in his homologation battle against the CSI couldn’t stop him now. In the colours of NART the Ferrari duo managed to snatch the drivers’ title from Hill and Clark, and Bandini played a pivotal role in the Mexican title decider. The perfect team player, Lorenzo first did his job by hounding Graham Hill into a spin at their approach to the hairpin. The contact led to Hill creeping to the pits to have a flattened exhaust pipe removed, which meant that his title chances were gone. Then, when Clark was hit by cruel fate in the final lap, Lorenzo understood he had to let Surtees by in order for his team mate to be champion. There’s always been talk of the Italian deliberately shoving Hill off but in an age of sportsmanship this was unheard of. Graham and Bette Hill were pretty upset at the time – the driver shaking his fist in anger when Bandini got dangerously close in previous laps, his wife known for some choice words on the pit wall – but five years later Graham gave a somewhat milder judgment when in Life at the Limit he described Bandini’s actions as “rather desparate”. It might have had something to do with Bandini having already met a tragic end when he wrote that, Graham probably not one to speak ill of the dead, but the fact that everybody loved Lorenzo will have played a part as well. It would have been very hard to be mad at him for long...

Too close for comfort...

Damage done... Bandini and Hill make contact in the hairpin, ruling Hill out of the championship.

Still, sometime in 1965, Jim Clark described Bandini’s enthusiasm in terms leaving little to the imagination, the Scot warning that Lorenzo was getting in danger of becoming another Mairesse. Perhaps it was the fact that Ferrari slumped back behind the British teams yet again that year. Although Surtees and Bandini scored a second place each in the first two races they were unable to keep up with Clark’s Lotus (but then, who was?) and the BRM pair of Hill and Stewart.

In sportscars, Bandini won the Targa Florio with Vaccarella while Scarfiotti was on his way to becoming a two-time European Mountain Champion, also taking the Nürburgring 1000kms with Surtees. In Grand Prix racing, however, Ferrari kept on struggling to the end of the year with their V8 and flat-12 engine variety

1966 would be different, however, the start of the year in some respects mimicking the events of early 1961. Again the British teams were caught unprepared for the new regulations, leaving Ferrari and their powerful 3-litre V12 engine well in front. But unlike five years earlier, the Scuderia was unable to capitalize on its advantage. The reasons why are well-known: team leader Surtees walked out in anger over Ferrari’s early-season focus on Le Mans, leaving the number-one seat to Bandini, with Mike Parkes and Scarfiotti again – fresh from the pair’s win in the Spa 1000kms – coming over from the sportscar team to support him. Lorenzo was in fact leading the championship after two rounds, for the first time in his career he had done so, but compared to being a safe number two away from the limelight this was something else. His first (and only) pole position and fastest lap in France went unconverted when in the dying moments of the race his throttle cable snapped. It was as if Bandini’s entire season snapped with it, since Ferrari somehow contrived to always give Lorenzo the car that broke down. At Brands he was unable to score any points since Ferrari wasn’t there – another case of the Italian general strike excuse striking again. Only at Zandvoort and at the Nürburgring did he put his first results on the board, two meagre sixths, respectively three laps and ten minutes in arrears, while runaway championship leader Jack Brabham put his third and fourth consecutive victory in the bag. There weren’t any wins in sportscars either, only a second place with Scarfiotti in the Nürburgring 1000kms. And when Ferrari finally came back with a resounding one-two at Monza it was Scarfiotti who took the spoils. Bandini had led the race, having made a great start from the second row of the grid but it was his car that was back in the pits with a broken fuel pipe on lap 5 and finally broke down with ignition failure after 35 laps. By that time, Ludovico had already taken the lead, however, with no plans to relinquish it, leading polesitter Parkes and Denny Hulme across the line by some six seconds. It was a magnificent win for the sportscar and hillclimb star, who seemed have pulled something extra out of the bag for his home crowd. In the US, Bandini’s single entry went out with engine failure, after which Ferrari decided not to bother going to Mexico for the season’s final event.

Scarfiotti's finest hours: leading the Italian GP on his way to a popular victory in front of the home crowd.

In sportscars, 1967 got off to a wonderful start for Ferrari. Bandini had been joined by Chris Amon, in both the Grand Prix team and the sportscar line-up, and the new pair led home a red one-two at Daytona, and then at Monza as well, their P4 leading the similar car of Parkes/Scarfiotti. In Grand Prix racing there was confidence to go around too when Parkes took the International Trophy in the new 312 while he famously dead-heated with Scarfiotti at Syracuse.

The team hadn’t made the January trip to South Africa, and fortunately the race of attrition at Kyalami had forced all the British favourites out. So approaching the Monaco GP with two non-championship race wins under their belts, and without any significant points deficit to catch up, things were looking good for the Scuderia. They entered two cars for Bandini and Amon. The Italian delivered by qualifying on the front row. It looked even better when poleman Brabham hesitated at the start, handing Lorenzo the lead on a silver plate. On lap 2, however, he’d already lost it to Denny Hulme. It was none of his fault since the marshals had been overdoing it a bit when covering the trail of oil laid down by Brabham’s Repco, which had failed spectacularly halfway down the first lap. Amidst the clouds of cement both Hulme and Stewart nipped by. After Gurney – who’d gone past Surtees and Bandini – and Stewart – who’d overtaken Hulme for the lead – went out on lap 5 and 6 respectively Hulme was back out in front followed by Bandini, Surtees, McLaren and Rindt. Clark was closing in on the quartet that soon became a trio when Rindt retired with a broken gearbox. On lap 28, Surtees’ Honda began to show a trail of smoke that turned out to be the first sign of a broken piston while Clark’s race was to be over ten laps later when a broken shock absorber sent the Scot spinning out of the race at Tabac. As McLaren had to ease off with a sickening engine the battle for the lead now firmly focused on Hulme and Bandini. The Italian was closing the gap tenth by tenth initially but then the gap started to widen again.

Bandini had led races as Ferrari’s number-one driver but thusfar failed to win one. Was the pressure getting to him? Hulme’s lead now up to 20 seconds, there was nothing more for Bandini to gain. Yet Lorenzo lost control of his car at the harbour chicane – his first-ever genuine driver error. The Ferrari’s left rear wheel clipped the barrier, spinning it around. When it hit a trackside pole the car was overturned, and as it skidded towards the harbour side a fuel tank was ruptured as it hit the straw bales. With Bandini trapped under his car, sparks ignited the leaking fuel. Heroic efforts from the marshals put the burning car on its feet again and the unconscious driver was pulled out. But it was all too late. Lorenzo was very badly injured, with third-degree burns over 70% of his body, especially on his arms and legs. He had also sustained ten chest fractures. What to do? Several options were considered, including flying in skin grafts from Italy or a specialist burns unit from England, or moving him to a hospital in Lyon that specialised in burn treatment. Eventually he died in agony three days later, succumbing to his injuries in the Princess Grace Polyclinic Hospital in Monte Carlo. He was buried in the town of Reggiolo in the presence of no less than 100,000 people. His loss was truly felt.

Afterwards there were questions asked about the timeliness of Bandini’s rescue. Should the marshals have arrived earlier? But considering the fact that six years later Roger Williamson’s car was left burning upside-down it was a miracle that the Monaco marshals managed to rescue Bandini from the flames at all.

Bandini’s name – and what a sensational name it is for a racing driver – still lives on in Grand Prix racing. Each year, the Lorenzo Bandini Trophy is awarded to drivers showing great character, spirit and determination in the fashion that the Italian was loved for. Its latest recipient is Sebastian Vettel. As his predecessors were, the young German was handed the trophy by Margherita Bandini in Lorenzo’s former residence of Brisighella, near Imola. Remarkably, it is the town’s residents who vote on which driver deserves the trophy each year.

Bandini’s death meant that Ludovico Scarfiotti and Mike Parkes were promoted to the Grand Prix team again. Ferrari ran a three-car team the two following races, finishing fourth, fifth and sixth at Zandvoort, but at Spa Parkes suffered a horrible first-lap accident. Ludovico ran home an unclassified 11th but his heart was out of it. First Bandini, and now his long-time sportscar team mate, with whom he’d finished second at Le Mans the week before, was very badly injured. Soon after the race he decided to quit Ferrari.

In 1968, Ludovico was back on two fronts, as a Grand Prix driver for the Cooper team in what would prove to be the team’s swansong season, and as Porsche’s new signing for both the World Sportscar Championship and the European Mountain Championship. After a false start at Kyalami with Maserati-engined T86s, Cooper switched to BRM engines on their return to Europe. It didn’t make the cars any quicker, as Scarfiotti lined up at the back of the grid at Jarama and Monaco, but they proved reliable enough to have the Italian survive these two races of attrition, as he finished them both in fourth – out of five remaining runners. Meanwhile, his first Porsche commitments had led to second place in the BOAC 500, 11th in the Monza 1000kms and retirements in the Targa Florio and the Nürburgring, on all occasions having teamed up with Gerhard Mitter. This young German had been European hillclimb champion for the past two years, having taken over the mantle from Scarfiotti, and now the two were team mates in the 1968 championship, using Porsche’s all-conquering 910 Bergspyder.

It was the reason why Scarfiotti wasn’t present at the Belgian GP, in the weekend of June 9. So Scarfiotti’s team mate at Cooper, Brian Redman, was joined by local hero Lucien Bianchi, the Belgian having already been Ludovico’s team mate at Monaco. Lucien’s Cooper also lasted the distance there and even finished one place ahead. It made him a worthy replacement for Scarfiotti at Spa. The steady Italian was in the Bavarian town of Rossfeld to contest the Obersalzberg hillclimb for Porsche. He wasn’t to compete in it. During Saturday practice something broke ahead of one of the corners and poor Ludovico was a passenger after that, his Bergspyder spearing straight off the road into a clump of trees. When the news of his death reached Spa, the feelings in the paddock matched the gloomy atmosphere at the Ardennes track.

Some months earlier we’d already seen the mercurial arrival and destructive departure of the next Italian in a Grand Prix Ferrari. Andrea De Adamich was a success in Italian F3 in 1965 and did the business for Alfa in the 1966 European Touring Car Championship, earning himself a place in the Ferrari Grand Prix team by the end of 1967. In the non-championship F1/F2 race at Jarama, Andrea finished ninth after suffering a puncture but he was given another chance in the 1968 South African GP. Amazingly, he outqualified his team mates Amon and Ickx but a spin into the guardrail on lap 14 ended his race prematurely. Back in the Ferrari in the Race of Champions, he threw it away by crashing mightily in practice, sustaining severe neck injuries that ruled him out for the rest of the season. Andrea survived but he’d lost his momentum and despite a victorious campaign in the F2 Temporada on his comeback for Ferrari, he would never reach his old level again.

By that time, Giancarlo Baghetti was more of a journalist than a racing driver, enjoying the good life and only guest-starring at his home GP. Since leaving Ferrari at the end of 1962, Baghetti’s career had been spiralling downwards. The ATS adventure was nothing short of a disaster, and when Bandini became the new number two at Ferrari, Baghetti took his place in the vacant BRM P57 at Scuderia Centro Sud. After two seasons with the perennial minnow team Giancarlo even stepped down to Italian F3. He would be the one to survive, though, focusing on his journalism and photography – for Playboy no less! – after his final guest appearance at Monza in 1967, driving a third Lotus 49. The year before he’d been out in a Reg Parnell-run Ferrari 246, the first private Ferrari entry since 1961 – which had been Baghetti’s FISA car! – and also the very last.

Baghetti's final Grand Prix appearance, guesting in a third Lotus at Monza in 1967.

The next Italian to find his way into a Ferrari seat was busy becoming the European Mountain Champion in the inaugural production-car class in 1967, driving his Alfa GTA up the hills to great effect. Coming from a wealthy Roman family, Ignazio Giunti had been racing Alfas since his teenage years. And now, on the back of his hillclimb title, he was progressing to the summit of Alfa’s motorsport activities. For 1968, Autodelta signed him as a regular for their sportscar programme. Sharing a T33 with Nanni Galli, who would one day also drive a Ferrari F1 car – for one day – Ignazio took second in the Targa Florio, heading the other Autodelta pairing of Bianchi/Casoni, a fifth in the Nürburgring 1000kms and a fourth (and a 2-litre class win!) at Le Mans. Galli and Giunti weren’t so lucky in 1969, retiring from almost all the events they entered.

Still, Ferrari had seen enough to sign him for their 1970 sportscar programme. Paired with old hand Nino Vaccarella in the behemoth 512S, Ignazio was immediately victorious in the Sebring 12 Hrs. At Monza, they took the battle to Rodriguez and Kinnunen, giving the mighty short-tail 917K a real run for its money, while in the Targa Florio the big car was again the first Ferrari home, even though they were outsmarted by Porsche bringing the nippier 908 along for Siffert/Redman and Rodriguez/Kinnunen. While Porsche kept on winning, at Spa in the 917 and reverting back to the 908 for another victory at the ‘Ring, Giunti showed himself well, and Ferrari decided to give him his Grand Prix break on the new and improved Spa circuit.

The Ferrari GP team had been a one-man show in the three previous races, but lead driver Jacky Ickx had failed to make any impact. When the team arrived at Spa, Ferrari was still far away from the title-threatening form it was to show in the second part of the season. So it was decided to give a second car to Giunti, alternating with Tecno’s Swiss F2 hotshoe Clay Regazzoni, who was now busy cleaning up the 1970 championship. Ignazio’s debut at Spa was difficult to fault, as he brought his Ferrari home in fourth, giving the Italians their first points of the season. A job truly well done. But then Regazzoni mimicked that performance at Zandvoort, and again on his turn at Brands Hatch, while Giunti couldn’t quite repeat his Spa performance at the difficult track of Clermont-Ferrand. His 14th place at the finish was mostly due to a lengthy pitstop to repair a broken throttle linkage but while Ickx had qualified on pole Ignazio languished down in midfield. Clay’s second fourth place on the trot gave him the momentum, and Ignazio was duly passed over for the Nürburgring, the big-sized version of Clermont-Ferrand. Regazzoni promptly qualified an amazing third, and it didn’t really matter that he blew his engine in the race.

To end the issue, the pair were both given cars for the Österreichring and, of course, Monza. Giunti did really well to qualify fifth in Austria and was in contention for third place all through the race until a puncture dropped him down to seventh. At Monza, he lined up fifth again and battled in the lead group but he was soon in trouble with a misfiring engine. In all, a competent performance blighted by bad luck. But in contrast, Regazzoni was reaching for the heavens. Outqualifying Ickx in Austria and running the Belgian close for an extremely dominant (and team-ordered) one-two, and then winning in Italy in front of thousands of delirious tifosi – how could you not pick him over Ignazio?

So it was back to sportscars for Giunti in 1971. Coupled with Arturo Merzario, like he had been in the 1970 Nürburgring 1000kms, Giunti left for the season-opening Buenos Aires 1000kms hoping to get his revenge on the Gulf Porsches. Arturo was hoping for more too: he didn’t get to drive at the ‘Ring, since Ignazio had to give up after just two laps with fuel injection problems. He wouldn’t get the chance in Argentina either.

36 laps into the race Jean-Pierre Beltoise ran into problems with his Matra-Simca MS660. For almost two laps he frantically tried to reach the pits by pushing his car up the hill in the final corner going onto the finish straight. Then tragedy struck. Giunti, closely following Mike Parkes’s Ferrari and about to lap it, swooped by and struck the unsighted Matra mid-ship. Miraculously, Beltoise somehow escaped unscathed as he had just moved to the right-hand rear of the car, but Giunti’s Ferrari was turned into a burning coffin instantly. Team mate Arturo Merzario, standing in the pits, was the first one at the scene. Confronted with the ball of fire, Art didn’t hesitate and sprinted the 500 yards that separated him from the burning wreck, and just like he would do at the Nürburgring in 1976 pulled the driver from the blazing inferno. However, Giunti was already dead from the impact with the Matra, although some say he died half an hour after he was extracted from the car.

What had happened?

The sequence of events. Beltoise is cutting across the corner while pushing his Matra towards the pits, with little room to spare on the racing line. Going unsighted behind Mike Parkes's car, the Matra is struck with tremendous force by Giunti's Ferrari. Both cars immediately burst into flames.

At first, Beltoise was firmly blamed for the accident. He was arrested and charged with negligent homicide, then released on bail, on the demand that he would be at the court's disposal for trial in Argentina within two months. Back home in Paris, there were voices from Italy demanding a life ban from motor racing and eventually Jean-Pierre had his license revoked for six months. It was indeed a stupid and irresponsible thing to do, pushing a car across the track while not having the sense that he was endangering himself and others by doing so. Moreover, he didn’t push the car alongside the track – which would have been the long way around in his uphill struggle – but instead took a shortcut, actually cutting across the racing line. This left the drivers the dangerous choice of going around left – where Beltoise at one time didn’t even leave enough room – or right, which in a left-hand corner meant going around the outside. Also, the situation would have changed lap by lap. Knowing where the Matra was the previous lap didn’t help the next time around. Cars entering and exiting the pits during a busy refuelling period only added to the confusion.

Others disagreed with blaming the Frenchman – and very vocally, too. In the aftermath, Fangio and Bonnier spoke absolving words while Louis Stanley – who was to become Beltoise’s team boss one year later – argued the other way too, just like he had done in the Regazzoni/Lambert incident, where initially the blame was also put at the surviving driver’s feet. There were yellow flags warning of the danger, 'Big Lou' wrote in Behind the Scenes, and Giunti must have seen Beltoise pushing his car on the previous two laps. The fact that Giunti hadn’t slowed down – as is proven by his lap times – seemed damning as well. Furthermore, you aren’t supposed to overtake under yellows.

Moving images that were recently rediscovered shed new light on the accident. You be the judge...

But was he trying to overtake? Others state that Parkes – equally surprised by the location of the Matra – darted to the left to avoid, leaving Giunti exposed in his wake. Or perhaps Giunti thought that Parkes was simply moving over for him. A third possibility is that Giunti was about to pit for fuel himself – the fact that Merzario was waiting in the pits with his helmet and gloves on seems to bear that out. The point is confirmed by locals who know the track better than anyone else: that final corner is just not for overtaking. Also, the preceding corner is a hairpin that takes the final corner out of view until the very last moment. So was Stanley simply trying to rewrite history?

Mike Parkes, on the other hand, blamed the marshals for doing nothing except waving their flags. But then, what were they supposed to do? The handbook said nothing about forcefully stopping a driver from pushing his car. Why should Beltoise have been disqualified when another driver, Gilles Rouveyran, did exactly the same thing and was classified as a finisher? So it apparently paid to carry on. It could be argued, however, that car that has run out of fuel is one that is suffering from a ‘mechanical failure’, which is the situation under which the marshals were allowed to act. Doubts about the interpretation of the relevant section of the International Sporting Code probably led to the fatal indecisiveness by the organizers and their marshals.

There were more shambles in the accident’s aftermath as several drivers, led by local driver Veiga, chose to ignore the red flag initially shown at the start/finish line. With the race continuing in a practical sense, the organizers then decided to withdraw the red flag instead of enforcing it.

The rescue attempts and the shocking aftermath...

So what did Beltoise himself think afterwards? This is what he said on French television: "I think that the accident was bound to happen as it was caused by an appalling number of circumstances. I think that most drivers would have acted as I did... they would have pushed the car, they would have tried to go back to the pits... I was at the end of a rather slow bend and there was plenty of room on the road to pass. The road was quite wide and I never thought there was any danger. Anyway, I had to take the car away from the middle of the road, because it was stopped in the middle. Before the accident I never felt I was personally in danger nor did I feel that I was endangering other people's safety. I shall certainly not stay for the next event because the organisers have asked me not to compete. Personally, I would not have taken the decision to refuse to compete in that event because I was committed to do so and also because I think this accident was caused by a combination of circumstances and it did not occur through my fault."

In the end, after the matter dragged on for too long, as had been the case in the Regazzoni/Lambert affair, the governing body assigned each involved a third of the blame. That may seem a diplomatic solution but it was probably just. Beltoise was blamed for recklessly pushing his car across the middle of the track instead of alongside it. Giunti was blamed for overtaking Parkes under a yellow flag, while the organizers were held responsible too since their marshals should have stopped Beltoise from pushing his car or at least helped him push the car off the track. Poignantly, it was only from October 11, 1971 that the FIA Yellow Book included a regulation leading to the immediate exclusion of a car being pushed along the track. This meant that pushing a car was still legal at the time of Beltoise’s actions. So perhaps the FIA should have apportioned a quarter of the blame to itself…

The second period of Italians driving a Grand Prix Ferrari wasn’t quite over yet since Giunti’s new team mate Arturo Merzario would be a steady second or third driver for the Scuderia’s F1 team until the disastrous 1973 season. But Lauda’s arrival and the return to success changed it all. Niki Lauda was a new kind of driver for the team, and for F1 as a whole. As far from a mediterrenean character as can possibly be, the Austrian built the entire team around him, instead of arriving and driving every other week and living the Grand Prix driver lifestyle in between. It was perhaps the most important reason for Ferrari shying away from emotional Italians as his drivers.

As for this second generation of Italian Ferrari drivers, Baghetti, Bandini and Scarfiotti probably weren’t as talented as Castellotti and Musso before them. Giunti might have been a proper Grand Prix driver for Ferrari if it hadn’t been for Regazzoni’s stunning arrival on the scene. Ascari’s successor wasn’t among them but they still carried Ferrari’s torch for a while. And with Bandini, Scarfiotti and Giunti all dying in the harnass there is still this undeniable sense of what might have been.