1966 International F3 Temporada

It's never too late to revive old passions

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- February 21, 2024

Related articles

- 1949 Brazilian Temporada - Brazil's forgotten racing days, by Lorenzo Baer

- The 1960-1975 South African Drivers Championships - Grand Prix at the Cape, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/Rob Young

- 1967 Argentinian F3 Temporada - Time to go south again!, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Argentinian F2 Temporada - The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1969 Tasman Championship - Something that Chris Amon did win, by Tom Prankerd

- 1970-1975 Tasman Championship - Back to Pukehoke for a revival of F5000 Tasman days, by Gareth Evans

- 1971 Colombian F2 Temporada - When Formula cars roared in the Coffee Land, by Lorenzo Baer

- Cuba, Bahamas, Puerto Rico - Racing Juniors in the tropics, by Lorenzo Baer

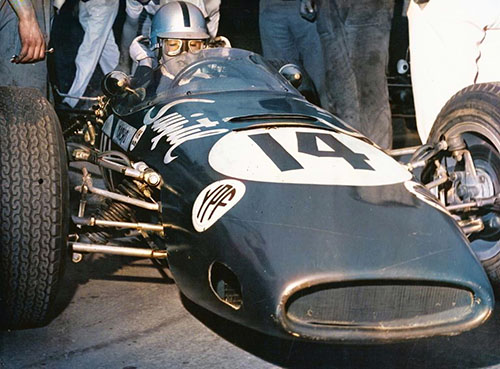

Who?Silvio Moser What?Brabham-Cosworth BT16 Where?Rosário, Parque Independencia When?1966 Gran Premio Internacional Cuidad de Rosário Acindar S.A. |

|

Why?

1966 marked the year of consolidation for Formula 3, a category that was now in its second incarnation. After the end of Formula Junior in 1963 (which had replaced the original F3 at the end of the 1950s), it would take a few years for the restructured category to take on its own shape. The years 1964/'65 were still surrounded by much of what was left of Formula Junior, as, for example, with cars from the old category still being eligible to compete in F3 events.

But the time had come to begin a new journey. With the kick-off made by the main motorsport powers of the time (England, France and Italy), a whole new generation of machines appeared in the fight for the world’s grassroots motorsport domination. Formula 3 now had its own face, its own identity. And the starting point of this new phase would be the lands south of the equator.

The Temporada

The South American representation in international motorsport, until the beginning of the sixties, was practically made up of drivers from three nations: Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. While the last two had their flashes with some excellent drivers (such as Chico Landi and Fritz d'Orey for the Tupiniquins, and Alberto Uría for the Gauchos), Argentina was a unique case – not only in the context of the region, but also on a global scale.

In addition to generating one of the most talented generations of drivers ever seen on race tracks, the 1950s Argentine driver crop became an exceptional marketing tool for promoting the land of tango and Argentine domestic motorsport. Juan Manuel Fangio, Carlos Menditeguy, José Froilán Gonzalez, Onofre Marimón and Roberto Mieres were some of the names that elevated Argentinean motorsport to a global status – and who also demonstrated that the world of motorsport was bigger than the one confined to the northern hemisphere.

Due to the successes achieved by these drivers, it was almost a natural move for some international races to be carried out in Argentine lands. The Gran Premio de Argentina, held in Buenos Aires, became a very popular event during the 1950s, taking advantage of the great success and fame of Argentinean drivers.

But in addition to this official race, there was another motorsport attraction for international drivers in the lands around the Rio de la Plata. Shortly before the establishment of the Argentine GP (something that only happened in 1953), what was called Temporada was already taking place in the region, in the form of a series of Formula Libre races that were attended mainly by Argentine, Brazilian and Italian drivers.

The Temporada began to grow in popularity during the 1950s, as it took place during the winter months of the European calendar, and served the purpose of being an excellent preparation ground for drivers and machines, before the start of the official motorsport calendar. Furthermore, since the Argentine GP usually took place in the first few weeks of January, this provided an opportunity for the drivers to re-accustom themselves to a competitive environment before the 'moment of truth'.

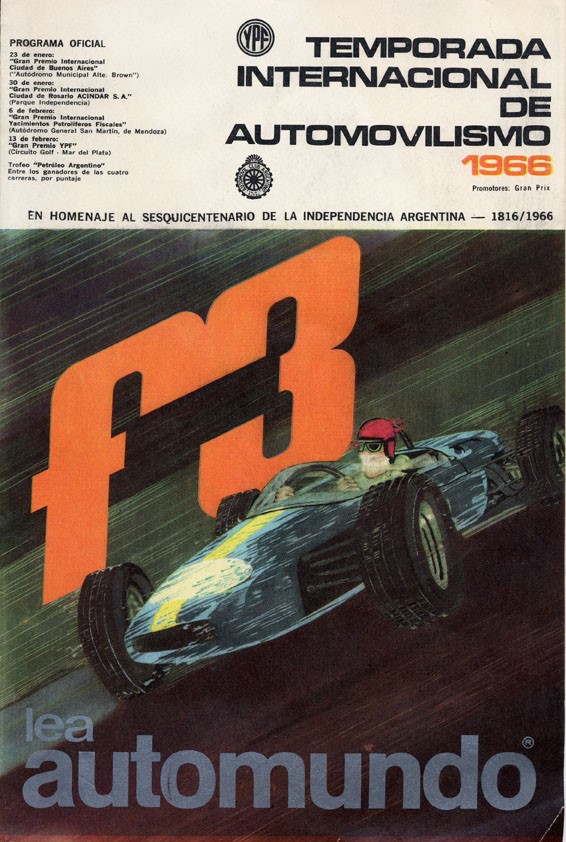

Official programme of the 1966 International Temporada.

Both the Temporada and the Argentine GP coexisted harmoniously until 1960, when it was announced that Buenos Aires would not return to the Formula 1 calendar for the following year. This coincided with a period of decline in Argentine motorsport, as the great generation that had shone on the tracks in the previous decade was now moving along, leaving a huge void in the future.

A four-year hiatus was necessary for Argentine motorsport to re-emerge (in a timid way) on the international scene. In 1964, what was now called the Temporada Internacional was reestablished, promising to be the starting point for a new phase of motorsports in the country. Open to FJ, F2 and F3 cars, this edition would feature mainly Argentine, Italian and Swiss drivers, who would compete in a mini-championship composed of four races. The 1964 edition was easily won by Swiss driver Silvio Moser, who destroyed the opposition by winning all four events.

Despite the modest entry list of this first edition of the reformulated Temporada, the championship was a success with the public. Furthermore, the championship was excellent for Argentine drivers, who reconnected with their counterparts from the old continent. However, the 1965 edition, which was scheduled to take place the following year, was canceled, simply due to a lack of funds to raise the event.

It was only in 1966 that the lessons of the '64 edition could truly be put into practice. In addition to restricting the championship to just one category, Formula 3, the locations that would host the rounds had a greater commercial and visual appeal. For example, Buenos Aires, which had been home to two events in the 1964 Temporada, would now host only one race, making room for an event in the bathing resort of Mar del Plata.

Another important decision was that more drivers and teams were to be invited, some of which were the most professional on the international Formula 3 scene. Entries were carefully inspected, and the driver's performance was analysed in line with the expected championship level. Another factor valued by the commission was the origin of the drivers, since this time it was necessary to live up to the name of Temporada Internacional (in English, International Season).

The preparation for the Temporada: cars and teams

At the end of the registration period, 26 vehicles were accepted for the competition in Argentina. The overwhelming majority were Brabham cars, which was the machine of choice for 16 of the drivers. Several models of the brand would be present, with the types BT10, BT15 and BT16 running simultaneously in races. The main teams to use the Anglo-New Zealand manufacturer's cars in Argentina were the Stirling Moss Racing Team and Charles Lucas Engineering.

The first, as the name suggests, was a venture controlled by former driver Stirling Moss, aiming to promote promising British drivers on the world stage. For the races in the Temporada, Moss had selected his best driver, Charles Crichton-Stuart. Known best for his role at Williams in the late 1970s (being the main responsible for brokering the agreement between the team and the Saudia sponsorship), Stuart was a promising driver in the early 1960s. In 1965, the driver had won three prominent races in F3: the X Prix de Paris and XXI Coupe du Salon, both held in Linas-Montlhéry, in addition to the XVII Internationales Sachsenringrennen. Such results promoted Crichton-Stuart to one of the main favourites of the Temporada.

But the driver would not have an easy life in Argentina, with his main challenger materialising in Charles Lucas Engineering, a team with an impressive rise in the F3 scene. On account of their performances, for 1966, the team had signed a lucrative agreement with Team Lotus, which would supply brand-new Type 41 models and would turn Charles Lucas into a semi-works team. However, at the time of shipment to the southern hemisphere, the cars were not yet ready – to this end, the only solution found was to take the venerable Brabhams BT10, which had defended the team so bravely in 1965.

The team's No. 1 driver of the Temporada would be Briton Jonathan Williams, who had won two rounds of the Italian F3 championship, as well as the Grote Prijs van Zolder, in Belgium, all in 1965. As teammates, Williams would have compatriot Piers Courage, who had achieved excellent results in the Italian and French national F3 championships, as well as the Argentine 'Cacho' Fangio, son of five-time world champion Juan Manuel Fangio.

Father and son in the same photo. Juan Manuel Fangio and Cacho Fangio in a promotional photo for the Temporada. (credits Arquivos de Mar del Plata)

Despite never being officially recognised as a son by Juan Manuel Fangio, Oscar Espinoza or 'Cacho', as he became known on the tracks, was seen in the constant presence of his 'father'. This was because Juan Manuel Fangio never married the mother of his son, but the driver was present when 'Cacho' began to follow his path in motorsport. This relationship explains a lot how 'Cacho' managed to be part of Charles Lucas during the 1966 International Temporada: having the shadow of the Fangio name was a prize for any driver in the sixties.

Another team that could also surprise in Argentina was The Checkered Flag. The team/constructor was born in the early sixties, being just one of the dozens of FJ vehicle manufacturers at the time. As the decade progressed, the company began to rationalise its structure, abandoning the manufacture of its own vehicles to focus on managing solely the racing team.

To this end, The Checkered Flag became a regular Brabham customer, taking a Brabham model BT16 to Argentina in 1966. The driver who would represent the team in the Argentine circuits would be Chris Irwin, who, until mid-1965, had defended the colours of the official Merlyn F3 team. In the end, the Briton made a wise decision: after the swap, Irwin won two international races, in addition to finishing on the podium in two others.

For analysts, the main threat to English dominance in the Temporada would come from the Société des Automobiles Alpine, which would take a full squadron to the pampas. Despite having quite irregular appearances on European grounds throughout 1965, the Alpine cars were closely watched by the other teams.

This was due to the team taking a large package of modifications that would be tested in Argentina – and the main one being the propulsion of the machine. The old 90hp Alpine/Renault R8 engine had been replaced by an updated version, which now reached 106hp. This was certainly an encouragement to the team's two main drivers, Frenchman Henri Grandsire and Belgian Mauro Bianchi (Lucien Bianchi's younger brother). In addition to them, Argentine Carlos Pairetti was invited to join the team's squad during the Temporada.

There were certainly other very interesting attractions on the grid: the Escuderia Argentina Automondo, a team sponsored by the automotive magazine Automundo, in partnership with the Automovil Club Argentino. No less than six drivers were listed by the team to participate in the championship: Nasif Estéfano, who also raced in the last edition of the Buenos Aires GP in 1960, would have a Brabham BT10 at his disposal. In addition to him, Juan Manuel Bordeu (Brabham BT10), Jorge Cupeiro (Brabham BT15), Andrea Vianini (Brabham BT15), Vincente Sergio (Brabham BT15) and Nestor Salerno (Brabham BT15) were listed in the team.

Lining up a car on the grid in the old-fashioned way nothing like pushing a Brabham into the starting position.

(credits Fotos Viejas de Mar del Plata, colourised with Palette FM)

The Martinelli + Sonvico Racing Team left for Argentina with a squad made up entirely of Swiss drivers: a young Clay Regazzoni shared space with an already experienced Silvio Moser, with each having a Brabham at their disposal: for the first a BT15 model, while Moser would race with a BT16 type. On the other hand, the Jochen Neerpasch Racing was completely German: in addition to Neerpasch himself, Karl von Wendt would complete the German duo, which was armed with two Lotus 35s.

In addition to these, there were only a few teams left consisting of one car: Goodwin Racing, which would be represented by John Cardwell and his Brabham BT15; the traditional Scuderia Sant'Ambroeus, which had shipped Carlo Facetti and a Brabham BT10 to the southern seas; in addition to Walter Flückiger (Lotus 35), Martin Davies (Brabham BT10), Picko Troberg (Brabham BT15) and Alfredo Simoni (Wainer F3) who would race as privateers in the championship.

The two peculiarities worth noting are: the Lola T60 from Stephen Conlan Motor Racing driven by Frenchman Eric Offenstadt – a rarity on the F3 grids, as only five machines of this type were produced by the British manufacturer. The car was originally built to F2 specifications, but at Offenstadt's request, the Lola was converted to F3, replacing the original BRM engine with a Cosworth.

The second was the Brazilian-built Willys-Gávea, nicknamed 'Canário' (Canary) due to the vehicle's bright yellow colour. The car was essentially a rebuilt Alpine, as the chassis was reused from a car from the French brand, and the engine was also the same Renault R8, modified in Brazil to reach something near 96hp. The car's big difference was its bodywork, which was made entirely of aluminium, something that contrasted with the rest of the field of cars made from composite structures. The team's driver would be Wilson Fittipaldi Jr, Emerson Fittipaldi's older brother.

1. Gran Premio Internacional Ciudad de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires, variant n° 3)

The first cars began to arrive in Argentina a week before the start of the official races. While some teams had no problems getting their vehicles through Argentine customs, others weren't so lucky. One example was the Brazilian Willys team, which, after a problem involving documentation and a series of errors by Argentine inspectors, had a serious query with customs police officers. In the end, the Argentines admitted their mistake and the team was allowed to go through.

The destination of all was the Autódromo Municipal Ciudad de Buenos Aires (known today as the Autódromo Oscar y Juan Gálvez). Of the various circuit variations available, the one chosen for the first stage of the Temporada would be nº 3, roughly 3920 metres long. The greatest characteristic of this variation was its high-speed layout, especially in the sector between the Cúrvon nº 8 and the Horquilla bend. Also in this part of the track was located the 'Ascari' curve, the most technical part of the circuit, simply because this high-speed right turn gave no margin for error.

The real activities on the circuit itself began on Wednesday (four days before the race), when the first drivers ventured onto the Buenos Aires track. Both this day and the next one (Thursday) did not serve as much of a parameter in relation to the times, as the Argentine drivers were still feeling their new F3 cars; meanwhile, the foreigners took the opportunity to learn the shortcuts of the Argentine capital's circuit.

Cacho Fangio's car arrives at the Buenos Aires race track, just before the opening session for the 1966 F3 Temporada. (credits Historia del Autodromo de Buenos Aires)

On Friday, times improved substantially, which demonstrated the level of competitiveness that could be expected in Sunday's race. Chris Irwin was swiftly adapting to the track, posting a lap of 1.41.7, almost a second faster than his closest pursuer, Andrea Vianini. This day was also marked by Nestor Salerno's accident, which destroyed his Brabham at the 'Ascari' curve – luckily, the driver emerged unharmed from the accident.

On Saturday afternoon, official training took place at Autódromo Municipal Ciudad de Buenos Aires. The Brabhams demonstrated vast superiority over the rest of the field, with the British drivers standing out. Williams and Irwin were playing with the opposition, pilling up faster laps. Piers Courage followed the pace of his compatriots, also dictating the rhythm of the classification.

When Courage finally managed to set the fastest lap in qualifying, the Englishman had a hard time. On his slow-down lap, the driver lost control of the car (also at the 'Ascari' curve) after a carburetor failure, colliding with one of the circuit's protection fences. It was another car that was destroyed in an accident, and, again, the driver escaped with just a few scratches.

After clearing the track, the practice session resumed for a few more minutes. It was enough time for Jonathan Williams to set the fastest lap at 1.41.0. In second was Chris Irwin, two tenths of a second behind. Courage was still in possession of the third best mark, but as the accident would prevent him from competing in the race the following day, third place on the grid went to the Swiss Silvio Moser.

The system chosen for the race in Buenos Aires was that of elimination heats, which would trigger a final race. Initially, the drivers were divided into two groups of 12 cars. The first group would be made up of cars that qualified in odd positions on the grid (1st, 3rd, 5th placed and so on), while in the second group the evens would race. The final times of each driver in their respective heat would be used to form the grid for the final race, which would bring together all the drivers, in another heat of 50 laps.

Juan Manuel Bordeu poses next to his Brabham. The driver also received his share of attention during the Temporada, especially during his duel with Facetti in the first round of the championship, in Buenos Aires. (credits A todo)

The cars of the first heat lined up on the grid at 3pm and after the flag given, by none other than J.M. Fangio himself, the drivers went down the main straight of the Buenos Aires circuit. Moser had a spectacular reaction time at the start, taking the lead of the race in the first few meters. Jonathan Williams, who was starting in first position, on the other hand, had a miserable departure. At the end of the first lap, the Briton was only in fifth place, having also been surpassed by J.M. Bordeu, Carlo Facetti and Picko Troberg.

On the third lap, there were some changes in this small group: Facetti had managed to overtake Bordeu, while Williams began his recovery in the race, after overtaking the Swede Troberg. On the next lap, Williams continued his momentum, with the victim this time being Bordeu, who now lost positions successively. And Williams' charge didn't stop there, as Facetti was another to give in to the Briton's withering advance.

After this manoeuvre, the positions practically stabilised for the rest of the race. The only real attraction was the duel between Facetti and Bordeu, which lasted until the final lap – after a couple mutual overtakes, it was the Argentine who came away with the upper hand, finishing in third place. Meanwhile, Moser led the race from start to finish, with Williams just a few tenths behind at the finish line.

After a few minutes, it was the turn of the second groep to perform on the Argentine capital circuit. Release sign given and again it was a Brabham that was in front: John Cardwell took the lead, with Chris Irwin falling to second and “Cacho” Fangio in third. The fight between the two Britons promised to be a great spectacle, but it ended up being just an expectation. On the same lap, Cardwell had problems with his car, while on the following lap, Irwin's Brabham gave way, forcing the driver to retire from the race.

These problems allowed Estéfano (who had had problems at the start) and Vianini to close by. The two quickly overtook 'Cacho' and began to open up the rest of the field. Vianini led most of the rest of the heat's laps, but in the end Estéfano's experience prevailed, with him crossing the finish line almost two seconds ahead of his compatriot. In third came the Frenchman Offenstadt with his Lola.

After the end of the second heat, it took more time than expected to gather all the cars on the starting grid for the final race. Due to the delay, Argentine organisers chose to reduce the duration of it, reducing the number of laps to be contested from 50 to 35. For it, 22 machines were ready to compete for the trophy of the first round of the 1966 Temporada Internacional Argentina.

Moser, Williams and Estéfano shared the front row. On the second row were Bordeu and Vianini. On the third row were Facetti, Offenstadt and Regazzoni. The only two cars that did not return for the final race were Alfredo Simoni's Wainer, which had mechanical problems, and Cardwell's Brabham, which, after abandoning the second heat, negotiated his car's steering arm with Irwin, so that The Checkered Flag driver could replace the broken part of his car and managing, somehow miraculously, to compete in the final race. As would be observed, this move would be decisive in the final result of the contest.

Chris Irwin's scarlet Brabham was a common sight in the top positions. The Temporada title narrowly escaped the hands of the British driver. (credits Historia del Autodromo de Buenos Aires)

As the flag was lowered for the last time in Buenos Aires, Moser once again took the lead, closely followed by the trio made up of Bordeu, Facetti and Vianini. The order would remain the same until the fifth lap, when Moser's clutch failed and the Swiss dropped out of the race. Bordeu took the lead ephemerally, as less than two laps later, Williams and Irwin, who were at an overwhelming pace, managed to overcome all the leaders to secure the first two positions for England. Williams first assumed the leader role, but on lap 10, it was Irwin's turn at the front. This shook Williams, who remained in Irwin's rear view mirror for laps.

Offenstadt also had a good race in the surprising Lola, rising to third place in the final stages of the race. But the Frenchman's ambition was beyond what his car could perform, and the driver lost important positions after overdoing it in one of the corners. This allowed another Brit to close in on the leaders; this time the Stirling Moss Team driver Charles Crichton-Stuart.

However, while everything seemed to indicate that the podium would be completely dominated by the English drivers, a stroke of hope enlightened the Argentine fans. With a few laps to go, Williams miscalculated a manoeuvre over Irwin. Instead of moving up to first, the driver ended up skidding off the track, losing irrecoverable time. This allowed Stuart to move up to second, and Estéfano, who was at some reasonable distance, to achieve a great third place.

The race ended with Chris Irwin securing his first victory of the 1966 Temporada, more than half a minute ahead of second-placed Charles Crichton-Stuart. Nasif Estéfano was the one who saved Argentina's pride in the first leg, clinching the final podium position in Buenos Aires.

2. Gran Premio Internacional Cuidad de Rosário Acindar S.A. (Rosário, Parque Independencia)

The second stop of the 1966 Temporada would be Rosário, located 300 kilometres northwest of Buenos Aires. In the 1960s, the city was already one of Argentina's main economic hubs, mainly due to heavy incentives in the city's industrial sector during Perón's government.

The circuit on which the race would take place was made up of urban roads, which surrounded the Hipodromo and Parque Independencia region, totaling 2779 meters in length. The track was one of the representatives of the golden era of Argentine motorsport – this can be attested by the fact that until the F3 race, the track record still belonged to J.M. Fangio, who had set it in a Formula Libre race in 1950!

Certainly, this was one of the determining factors in bringing an international race to the location again, as the track was not very suitable for the high-performance vehicles of the sixties. The circuit was cramped, with just one long straight, in addition to presenting few real overtaking points.

The teams with less powerful cars were more than satisfied in running on the tight track, which saw one of the Brabhams' great advantages (straightline speed) being neutralised by the Rosário urban circuit. The French Alpine and the Brazilian Willys benefited most from this, demonstrating in the only free practice session that happened on the circuit (on Friday) that they were at least closer to their rivals than in the Buenos Aires round.

On Saturday, the qualifying sessions took place. Two timed sessions were scheduled, lasting one hour each, with each driver being required to complete 10 laps in each, to have their times accepted for the final classification. In the first session, it was Belgian Bianchi who stood out, setting a mark of 1.36.5. Swede Picko Troberg came soon after, clocking a 1.38.0. Moser, with his repaired car, rounded out the top three with a 1.39.4.

Juan Manuel Bordeu's Brabham BT10 is pushed to the start line, in one of the races of the XV Temporada Argentina.

In the second session, times went down even further: Bianchi and Troberg remained firmly the fastest, clocking 1.35.7 and 1.35.9 respectively. However, the one who now appeared third was Briton Chris Irwin, with a 1.36.5. The Brabhams of Carlo Facetti and John Cardwell snatched the remaining positions in the top five, giving the final numbers on the starting grid of the Rosario race.

For Sunday, the heats competition system was chosen once more. Originally, the organisers' plan was for the cars to again be split into two groups, with each group competing in a heat of 20 laps, in addition to a final, which would add another 40 laps. But due to the drivers' complaints about the circuit (mainly due to the high consumption of the cars on the abrasive asphalt of Rosário), everything had to be rethought. Now, the Gran Premio Internacional Ciudad de Rosario would be held in three qualifying heats of 10 laps each, with the final being reduced to 30.

The first eight cars lined up on the Rosário track, just before 4pm. Given the start authorisation, Mauro Bianchi soon tried to secure the first position, with Pairetti, Crichton-Stuart, Cupeiro, Facetti, Bordeu, Williams and Flückiger following behind. This order remained the same until lap 5, when Facetti and Bordeau advanced through the field, largely due to the mechanical problems of Crichton-Stuart and Cupeiro. On the sixth lap, Pairetti was another one with problems, leaving Bianchi in a comfortable position in the lead.

And despite his problems, Crichton-Stuart continued in the race, until on lap 7 the Brabham engine overheated, forcing the driver to finally retire. At the same time, Bordeu and Facetti climbed up the standings once again, going to the second and third positions, respectively. Bianchi had finished in an easy first place, almost 15 seconds ahead of the Argentine and the Italian.

Just a five-minute break was enough for the cars from the second heat to line up on the Rosario grid. This race was marked by the duel between Moser's Brabham and Grandsire's Alpine. After starting at the front, the Swiss held the pressure of Swede Picko Troberg who, for four laps, was on the driver's trail. On the fifth lap, it was Grandsire who took the job of chasing down the Swiss.

The Frenchman was initially concerned with consolidating his position, as Cardwell had followed him in overtaking Picko. But the Englishman didn't stay on the pace for long, allowing Grandsire to turn his full attention to the Swiss Moser. The Brabham and the Alpine were together until the last lap, when the Swiss driver made a mistake in the entrance of the Lago curve and opened up enough space for Grandsire to pass, giving the second victory of the day for an Alpine car.

The general classification of this heat was: 1st, Henri Grandsire (Alpine); 2nd, Silvio Moser (Brabham); 3rd, Picko Troberg (Brabham); 4th, “Cacho” Fangio (Brabham); 5th, John Cardwell (Brabham); 6th, Martin Davies (Brabham); 7th, Jochen Neerpasch (Lotus).

The only Australian on the grid, Martin Davies, struggled during the whole Temporada. Problems with his Brabham BT10 married with bad luck affected all the driver's chances in the championship. (credits VadeRetro)

A few more minutes and it was time for the third heat of the day. The Argentinian Vianini took the lead, followed closely by the Swiss Clay Regazzoni. Offenstadt, Estéfano, Fittipaldi, Von Wendt and Irwin completed the classification after the first lap. But this didn't last long, as Estéfano lost several positions on the second lap due to an error in one of the corners.

The fourth lap saw new movements. The main one was Vianini, who also made a mistake and collided with one of the curbs on the streets of Rosário. The sensitive car could not withstand the impact and the driver had to withdraw from the race. This meant that first place fell into the lap of Regazzoni, who now had Wilsinho Fittipaldi as his immediate pursuer.

The Brazilian measured forces with the Swiss driver until lap 7 when Fittipaldi, trying to overtake Regazzoni, overdid it and lost control of the Willys-Gávea, spinning in the section between the Lake and the Hipodromo. The driver managed to return to the race, without damage to his car – but it was already too late, as the Brazilian had already dropped to eighth position.

Wilsinho's anxiety had almost certainly cost him victory, as less than two laps later, Regazzoni began to slow down at the front of the race. The Swiss showed no reaction when, in the final laps, he lost positions to Nasif Estéfano, Eric Offenstadt and Chris Irwin. At the end of the battery, it was discovered that the Swiss Brabham suffered from distributor issues.

But this was not a problem for Argentine Estéfano, who crossed the finish line first, after an excellent recovery run. It was certainly a memorable performance from the driver, as in addition to beating the entire field by the time of the checkered flag, Estéfano had also built a comfortable advantage of almost nine seconds over his closest pursuer – in this case, Eric Offenstadt.

The Swiss drivers from the Martinelli + Sonic Racing Team squad proved themselves as one of the most resilient teams of the Temporada, with at least one driver or another always competing for the top positions. Moser's victory in Rosario was the team's highlight during the series of races in Argentina.

Half an hour later, it was time for all the competitors to line up for the decisive race in Rosário. And when the flag was about to drop, the first five drivers on the grid jumped the start. Grandsire went ahead, while Bianchi, Estéfano, Stuart and Troberg followed closely behind. It proved to be Grandsire's last joy in the Argentine city, as when the cars returned to the grid to realign themselves for a new start, the car's gearbox was found to have ruptured.

In the second start – this time carried out without problems – it was Moser who led by the time of the first corner, followed by a compact pack containing Offenstadt, Bordeu, Bianchi, Facetti, Regazzoni, Troberg, Fangio, Irwin, Pairetti, Cardwell, Fittipaldi, Cupeiro and Estéfano. However, it didn't take long for some drivers to have their share of problems: Offenstadt lost control of his Lola just after the Lago curve and left the track with no chance of returning. Irwin, in turn, permanently stopped in the pits due to suspension issues.

On the second lap, the positions were maintained, and on the third, Moser and Bianchi had already opened a gap over the rest of the main group. Regazzoni, who was in fifth, had fallen to last, after a childish error in one of the corners. On lap 4, another change in the podium area after Facetti overtook Bordeu for third place.

This marked the ascension of Facetti in the race, who was also slowly closing in on Bianchi and Moser. This in no way alerted the Belgian and the Swiss who were locked in a private skirmish for the lead. It was only on lap 12 that Bianchi overtook Moser – and at that point, Facetti was already on the duo's heels.

However, the fight for the lead stabilised a bit while the midfield battle increased in intensity. Estéfano was dicing simultaneously with Troberg, Cardwell and Bordeu, who had lost several positions in the middle phase of the race. However, Estéfano prevailed in the clash, consolidating himself in fourth position.

With just a few laps to go, attention once again turned to the lead. Bianchi started to lose ground, and Moser didn't waste the opportunity, retaking the lead. Facetti and Estéfano followed, with the Belgian now holding on to a tenuous 4th place. But this was not the final act of the race; on the 28th lap, Moser was leading, with Argentine Estéfano now in second and Bianchi in third! Facetti, who did so well till now in Rosário, crashed in the curve near the Cochabamba Street.

This gave Moser peace of mind to cross the finish line in first, with a good advantage over second-placed Estéfano. In third place, the crumbling Alpine of Bianchi who had given the French manufacturer its first podium in the Temporada.

3. Gran Premio Internacional Yacimentos Petroliferos Fiscales (Mendoza, Autodromo General San Martin)

The historic city of Mendoza, located at the foothills of the Andes, would host the third stage of the 1966 Argentine F3 Temporada. The region surrounding the city was one of the richest and most prosperous in the country, mainly due to the oil fields that were in the municipalities neighbouring the capital of the province. Due to the wealth of the region, the task of attracting Formula 3 to compete in the provincial capital was not at all complicated – regarding this, the Mendoza GP would be sponsored by the Argentine state oil company YPF.

The track where the race would take place was located in Parque Central San Martin, located in the old center of the city. It was approximately 2650 metres long, and was mainly covered along narrow paths within the park, in an area close to what is nowadays the stadium of the Godoy Cruz football club. The track record obviously belonged to Fangio, who had set a mark of 1.49.2 with a Lancia D50 in 1956.

Ten years later, it was the turn of the Brabhams and Alpines to dominate the circuit. Once again, the drivers had little time to get used to the circuit, with free practice being allowed only on Friday. Due to the terrible heat that embraced drivers, cars and teams – according to press reports, the temperature throughout the weekend was well above 30 degrees – little could be enjoyed from this day, as the drivers wanted to preserve their machines as much as possible.

The next day it was really clear which drivers would adapt best to the Mendoza track. The drivers of the English squads were the ones who proved to be surprisingly fast in these adverse conditions, as three of the five best classified had the Union Jack next to their names: Jonathan Williams was the highlight of these, guaranteeing the best time of all, with 1.08.7, Crichton-Stuart secured fourth place while Chris Irwin would start fifth. The exceptions among the fastest were the Australian Martin Davies, who clocked the second best mark, with a time of 1.08.8 and Italian Facetti who had achieved a great third place.

For the following day, when the official races would take place, the Automovil Club of Mendoza once again repeated the format that had become the pattern of the Argentine Temporada: two semi-finals with a few laps, which would be used to set up the grid for the final race. The 22 cars were distributed in the two preliminary heats, each of 25 laps. In each heat, the first 10 (totaling 20 vehicles) would qualify for the final held in another race, this one lasting 50 laps.

The first series slightly favoured the Argentine drivers, as Irwin, Crichton-Stuart, Moser and Cardwell would only compete in the second heat. To this end, the driver who dictated the pace of the race was the Argentine Andrea Vianini, who quickly took first place, followed by Grandsire (Alpine), Facetti (Brabham) and Cupeiro (Brabham). Within a few laps, the contest became more selective, with Grandsire losing ground and dropping to fourth.

Halfway through the race, it was Vianini who was leading, followed at a distance by Facetti and Cupeiro, who were fighting a beautiful duel for second position. Cupeiro managed to overcome the Italian at times, but in the final laps it was Facetti's international experience that prevailed in the duel. Vianini had opened up such a comfortable advantage over his rivals that, in the final laps, the driver slowed dangerously. But nothing that would interfere with the Argentine's victory, who still finished two seconds ahead of Italian Facetti.

One of the representatives of the Escuderia Argentina Automundo, Andrea Vianini had good appearances throughout the Temporada, especially in Mendoza, where the driver even won one of the qualifying heats.

(credits VadeRetro, colourised by FM Palette)

Quickly, the cars from the second heat lined up on the grid – and, as expected, this was a more interesting race for the crowds. Silvio Moser took the lead of the race on the first lap, but this was shortlived, as on the second lap, Chris Irwin had already positioned himself as the leader of the pack. The Briton and the Swiss driver battled for a few laps until Irwin started to gain an advantage, leaving Moser in a terrible spot.

The Swiss found himself defending his second place, now threatened by Crichton-Stuart. Moser defended his position until the penultimate lap, when Stuart took advantage of a small gap left by the Swiss to take second place in the heat standings. But it was too late to catch Irwin, who was almost 10 seconds ahead of the two drivers.

Picko Troberg, who had an accident in the first heat and destroyed his car, and Clay Regazzoni, who finished last in the second, were the ones eliminated from the preliminary heats. Therefore, the 20 classifieds lined up for the final race in Mendoza. Right at the start, the winners of the heats were those who jumped in front: Irwin in first, Vianini in second. Behind were Facetti, Offenstadt, Cardwell and Estéfano.

Wilsinho Fittipaldi, who had started on the last row, had made a spectacular advance on the first lap, being in 6th place behind Estéfano on the opening of the second lap. But the Brazilian once again saw his luck abandon him, as in less than five laps, the Willys was heading towards the Brazilian team's garage, due to a broken belt.

Therefore, the Brazilian did not witness the biggest movements in the field that began to develop from lap 6 onwards. Firstly, it was Nasif Estéfano who overtook Cardwell. On the next lap it was Crichton-Stuart who stole the show, because after a devastating charge from seventh position, the Englishman had overtaken Andrea Vianini, with the race turning into a British duel for the lead in the land of tango.

Nasif Estéfano tangles with one of the curves of the Temporada. (credits F1 Forgotten Drivers)

While this was developing, another serious accident occurred in the Argentine Temporada. On lap 16, the universal joint of the driveshaft of German Jochen Neerpasch's Lotus 35 broke at the La Olla curve, with the vehicle leaving the track and seriously injuring a spectator – on the other hand, once again, another driver emerged unharmed from the accident (something that attested to the safety of the new F3 chassis).

On lap 20, Irwin remained in the lead, with just over 1 second in hand over Crichton-Stuart. Further back, Vianini, Estéfano, Offenstadt and Cardwell were in an intense dispute over third place. On the 30th lap, Stuart took the lead, with Irwin right on his tail. Behind the two, the order of the peloton remained unchanged, with Vianini fixed in the last position on the podium.

The final classification of the race seemed outlined until a few laps from the end Vianini began to feel something strange in his car. The driver started to drive very slowly and on the last lap the Argentine's car simply fell out of contention. Luckily, this did not become a calamity for the Argentines, as the driver who inherited the final position on the podium was another porteño driver, Nasif Estéfano.

Even so, this fact did not hide the superior performance of the British, who secured the highest positions in the race. Crichton-Stuart completed the 50 laps of the Mendoza GP in 58.13.6, a second and a half faster than second-placed Irwin. Due to these results, the final race at Mar de Plata had become essential in deciding who would be champion of the 1966 International F3 Temporada.

4. Gran Premio YPF (Mar del Plata, Circuito Golf)

The finest hour of the 1966 Temporada had arrived. Drivers and machines were now heading south, towards the resort and bath town of Mar del Plata. With great expectations, the organisers brought the final stage of the championship to the coastal city – to this end, the Argentine press quickly tried to give the race an unofficial title: the Monaco of the southern hemisphere.

Even though this statement seemed a bit exaggerated, there were certain reasons that promoted such thinking: the Mar del Plata circuit, made up of an almost rectangular shape, would have a large part of its route following the city's seaside boulevard. Furthermore, the city was popular with tourists throughout the year, but especially during the summer months.

The race would be decisive in all aspects of the championship – Nasif Estéfano led the general classification with 16 points, thanks to his regularity in all the races so far. Chris Irwin and Crichton-Stuart had 15 points each, which left them both within striking range. In other words, the rule was simple: of the three, whoever came first would be declared champion of the 1966 Argentine F3 International Temporada.

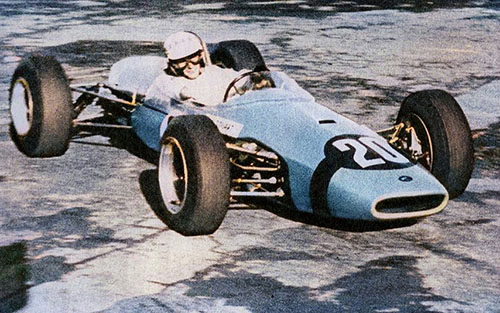

Cacho Fangio gets ready for the practice session at Mar del Plata, during the 1966 Argentine Temporada.

The first practice sessions began on Friday and, right away, the idea of the 'Monaco of the South' was dispelled: even though the landscape was stunning, the track soon proved to be a problem for the drivers. The asphalt was of poor quality, which increased the friction rate of the cars. Furthermore, the curbs on Mar del Plata's urban roads were too high, posing a safety issue: if a car collided at high speed with any of these, it would be catapulted towards the crowd on the sides of the road. Only a few straw barriers were placed around the 'track', which was by no means a concrete measure to solve such issues.

Because of this, few drivers tried to push harder on the first day of practice. The majority reserved themselves for just doing a few reconnaissance laps, trying to mark reference points on the circuit that would help them in the actual qualifying sessions, scheduled for the following day.

On Saturday morning, a new practice was carried out in which the drivers left everything they could on the platense track. A minimum of 10 timed laps was required for drivers to qualify for Sunday's races. In the end, the driver who managed to achieve fastest lap was Jorge Cupeiro, with a 1.28.36, something that aroused the complete joy of the Argentine crowd. Moser, with a lap milliseconds slower than the Argentine, came second, with a surprising Offenstadt in third.

Sunday dawned cold and damp in Mar del Plata. In the hours preceding the first heat, the rain became so heavy that the possibility of postponement, or even worse, cancellation, of the race was considered. But, due to some force majeure, the weather began to improve in the early afternoon, and, until the start, a strong tropical sun reigned over the city.

It was only at 4:55pm that the first heat started. Cupeiro, who had started first, was quickly beaten by Offenstadt, Regazzoni, Williams and Cardwell, after a poor start. Frenchman Offenstadt's lead was shortlived, as less than a lap later, Regazzoni was leading the field.

The following laps were the scene of a great spectacle provided by Cupeiro, who sought to regain his position with the leaders. On the fourth lap, the driver overtook Cardwell while performing similar manoeuvres on Williams and Offenstadt on the following laps. On lap 7, Cupeiro took the lead of the race, taking Williams along in his wake. Both managed to overtake Regazzoni, who quickly dropped from first to third place.

The most experienced Argentine driver on the grid, Nasif Estéfano raced on par with his European counterparts. Not surprisingly, in the last round, the driver still had a chance of keeping the title in the lando of tango. (credits F1)

The positions remained unchanged until lap 13 when the Regazzoni car began to slow down on the track. This was the opportunity that Offenstadt was waiting for, as the Frenchman moved into third position. Bianchi, who was following right behind, entered one of the corners too hard, spun and crashed into one of the straw barriers. Both driver and machine emerged almost unscathed from the accident, with the greatest damage done to Bianchi being the precious seconds lost due to the incident. Cardwell was another who had a hard time, suffering a terminal mechanical breakdown on the same lap. This allowed Facetti to move up to fourth, followed by Estéfano.

On lap 16, Offenstadt had problems engaging one of the gears of his Brabham in one of the circuit's curves and was another to spin and collide with the straw barriers. The French driver tried to quickly return to the race after the accident, but the car was stuck in the improvised protection. Only with the help of spectators who pushed the car out of the hay trap the Frenchman was able to return to the race.

Meanwhile, in the lead, the dispute entered into a more rhythmic stage. Cupeiro consistently increased his lead over Williams who was content to follow the Argentine at a distance. The same could not be said of the battle for third place, which saw Facetti and Estéfano fight a strenuous battle for the last spot among the top three. In the end, it was Estéfano who emerged victorious, achieving a great third place.

But it was Jorge Cupeiro who placed the blue and white flag at the top of the standings. The Argentine completed the 20 laps of the heat with a total time of 30.17.8. In comparison, second-placed Jonathan Williams completed the race in 30.29.9.

In the second heat, it once again looked like the Argentine flag would fly as Vianini took the lead on the first lap, followed by Moser, Crichton-Stuart, Bordeu, Davies, Grandsire and Irwin. However, on the second lap, it was the white and red of the Swiss flag that was leading, with Vianini and Bordeu (who had overtaken Stuart) close behind.

In the following laps, Moser tried to distance himself from his rivals, with Vianini becoming increasingly smaller in the Swiss driver's rear view mirror. But this did not discourage the Argentine driver, who, with the support of his compatriot Bordeu, continued to set a strong pace in the race.

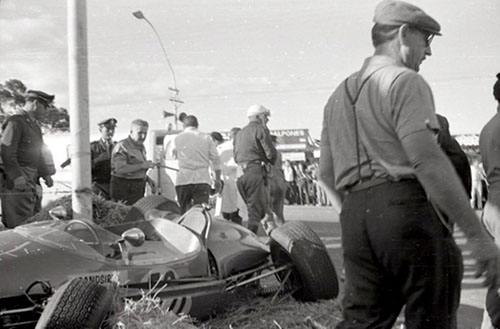

On the tenth lap, a serious accident occurred just after the pit curve. The suspension of Frenchman Henri Grandsire's Alpine could not withstand the bumps of the Mar de Plata circuit and broke, causing the driver to lose control of the car and go straight into the crowd on the sides of the track. Due to the speed of the vehicle and the high curb, the car was catapulted and only stopped when it collided with a pole. Three spectators were seriously injured, in addition to a 17-year-old boy, who died at the scene. Grandsire emerged with only a few bruises from the accident.

Grandsire's crash in the Mar del Plata race was the only major negative point of the 1966 Argentine Temporada. Even so, the accident demonstrated the importance of safety on circuits, especially the urban ones. (credits Periodico)

Even with this accident, the race was not interrupted. On lap 16, Crichton-Stuart took advantage of Vianini's hesitation to take third place. Soon after, this position turned into second, as Bordeu would also lose the position to the Briton. The order remained practically unchanged until the final flag, with only Davies managing to move up to fourth, after overtaking Vianini.

In the end, Moser prevailed after a great display of skill that put him almost eight seconds ahead of second-placed Crichton-Stuart. But this race was just the appetizer, as the moment of truth would only come in the final race in Mar de Plata.

It was already 7pm when the remaining 17 cars turned on their engines for the last time in the 1966 Argentine F3 Temporada. Moser jumped into the lead, followed by Vianini, Crichton-Stuart, Davies, Bordeu and Williams. Cupeiro, who had done so well in the practice sessions and in the preliminary heat, had problems with his Brabham BT15, leaving him well behind in the race. Until lap 6, the front group remained the same, until Moser made a rare error on his part, leaving a gap that was enough to let Vianini and Stuart go through.

The Argentine held off the pressure from the Brit for four laps, until Stuart finally managed to steal first position from Vianini. Another who also managed to improve in the race was Martin Davies, who was now in third, having overtaken Moser.

During the following laps, the confrontation between Vianini and Crichton-Stuart was intense when on lap 14, Vianini returned to the lead of the race while lap 16th, Stuart led the classification. On lap 18, however, Vianini was in front again. Further back, Estéfano, who was looking to recover from a bad start, was battling with Bianchi for the intermediate positions. Nasif was desperate to climb the field, as each new lap reduced his chances of fighting for the Argentine Temporada title.

Meanwhile, at the front, Vianini increased his pace, something that failed to affect Crichton-Stuart, Davies and Moser at all, who continued to follow the Argentine. Not surprisingly, on lap 24, Stuart was back in the lead. Between lap 25 and 29, two changes in the front group occurred: first Davies started to slow down before retiring, and then it was Moser's turn to disappear from the race due to a gearbox failure.

On lap 30th, this was how the front group was made up: Vianini (who had once again passed Stuart), the Brit himself, and the Frenchman Offenstadt, who had been advancing stealthily from the start, as well as 'Cacho' Fangio and Chris Irwin. The following laps saw a new offensive from Crichton-Stuart who subsequently resumed in first position, in addition to the increasing attentions of Offenstadt.

On the 35th lap, the Frenchman was up in second place, now setting his sights on Stuart. For a few laps the Brit managed to hold off the momentum of the Frenchman and his Lola, but on lap 38, Offenstadt performed the definitive manoeuvre of the race. No one else would take the driver's lead until the final chequered flag, with Eric Offenstadt crossing the finish line first, with a total time of 59.23.2, just a tenth of a second ahead of second-placed Stuart. In third, giving some sort of happiness to the audience present, was 'Cacho' Fangio.

Charles Crichton-Stuart, on his way to being crowded champion of the 1966 Argentine F3 Temporada, aboard the Brabham of the Stirling Moss Auto Racing Team. (credits Historia que Vivemos, colourised with Palette FM)

Although victory narrowly escaped him in this round, there was no reason for Charles Crichton-Stuart to be disappointed, as second place guaranteed him the title of the 1966 Argentine International F3 Temporada. The result was a spectacular achievement for the driver, as well as recognition of the efforts of the Stirling Moss Auto Racing Team itself. Second in the general classification was Chris Irwin, with Nasif Estéfano and Eric Offenstadt tied in third place.

Why to read me?

The publicity generated by the 1966 edition of the Argentine Temporada certainly went beyond what was predicted by the organisers themselves. The well-fought championship races with four different winners in four events (Irwin, Moser, Crichton-Stuart and Offenstadt) demonstrated that choosing Formula 3 was a wise decision that had resulted in a high level of competition at a lower cost than those associated with F2 or F1.

Another interesting point was the demonstration of strength by the Argentine drivers compared to their European counterparts: Vianini, Cupeiro and Bordeu were the big surprises, with each one having their highlight moment throughout the Temporada. However, it was the experienced Nasif Estéfano who embodied the toughest competitor to his British, Swiss and Italian opponents. Despite not having won a race, the driver remained in the fight for the title until the final race thanks to his consistency throughout the championship (just observe that only in the last race at Mar del Plata the driver failed to finish on the podium).

The Brabham that Nasif Estéfano used in the 1966 Temporada is currently preserved in a museum dedicated to the driver in the Argentine city of Concepción. The colours and details are exactly the same as those from 60 years ago.

And foreigners were certainly surprised by the performance and organisation of the Argentines, who had not organised an event on such a scale for a long time. Despite some safety issues, which were almost omnipresent at any motorsport event in the 1960s, the Temporada ran as smoothly as could be. The results of this were certainly observed when it was announced that the championship would be held again in 1967 – and increasingly qualified interested parties began to welcome the event.

Acknowledgements

- Brazilian Magazine Auto Esporte, March 1966 edition

- Argentine Magazine Automundo, December 1965 and January 1966 editions

- Special thanks to the Historia del Autodromo de Buenos Aires Facebook Page and the Archives of the City of Mar del Plata who preserved some photos of the events