Three generations of sportscar superiority

Author

- Mattijs Diepraam

Date

- March 3, 2010

Related articles

- Jean Behra - The fighting man, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Derek Bell - Master of Endurance, by Mattijs Diepraam/Chris Watkins

- BRP - Dad, Ken Gregory and their dream team, by Felix Muelas

- Jacky Ickx - Europe's Mr. Versatility, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Leo Kinnunen - The first chapter, by Sami Liikanen

- Porsche - Weissach's single Grand Prix win, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- The Rodriguez brothers - The kid and the Porsche hero, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/Josh Lintz

- Jean-Louis Schlesser - How Jo's cousin became a Monza hero, by Mattijs Diepraam/Andrew Winter

- R R C Walker Racing Team - Hallowed privateer, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

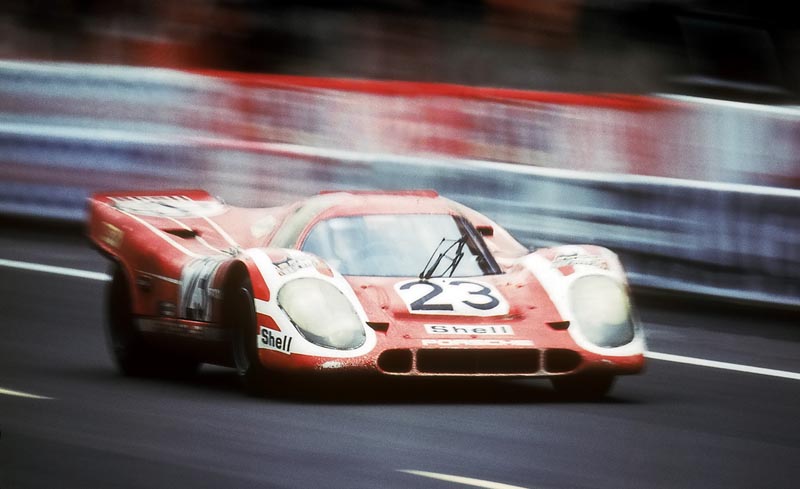

Who?Hans Herrmann What?Porsche Salzburg Porsche 917K Where?Le Mans When?XXXVIII Le Mans 24 Hours (June 13-14, 1970) |

|

Why?

Only a handful of racing drivers are among the best in both single-seaters and sportscars, Stirling Moss and Jacky Ickx being two of the most famous examples. Many Grand Prix greats merely dabbled with sportscars, and when they did have full parallel careers, such as the incomparable Juan Manuel Fangio, they couldn’t fully get to grips with the fendered machines. The other way around, many of history’s sportscar greats were Grand Prix drivers as well – only just not that good. Hans Herrmann, Jo Siffert and Jochen Mass represent three generations of two-timing drivers who shone on occasions in Grand Prix racing but were kingpins in Porsche’s huge success in sportscars.

Since World War II two marques have redesigned the top drawers of single-seater and sportscar racing. In Grand Prix racing, Auto Union, Mercedes-Benz, Alfa Romeo and Bugatti were put in the shade by a former Alfa privateer creating a legend that became the face of post-war F1. Around the same time, a former Auto Union designer and his son got set on rebuilding a company that would be the proverbial sportscar brand throughout the remainder of the century. Even though Porsche won in Grand Prix racing while Ferrari had its victorious spells in GTs and prototypes, notably in the sixties, the Weissach company was as much the yardstick in sportscars as the Maranello marque is synonymous for Grand Prix domination.

Since the start of the new century, however, Porsche embraces a customer-car policy that sees it selling its racing products by the dozens to numerous privateer teams, in what is usually GT racing’s B class. It’s been a while since Porsche was a force in prototype racing, though. Their recent RS Spyder did star in the LMP2 baby class, but factory support to the private teams running these cars – both through technicians and drivers – was the closest thing to a works Porsche effort. From the first RS550 entries by Porsche System Engineering in the fifties to the last time a 911 GT1 took part under the Porsche AG banner in 1998, the factory has been by far the most successful sportscar marque, at first by virtue of countless class wins, before dominating with numerous overall victories as well.

The magical number 23

One of Porsche’s most familiar faces in the fifties, leading on into the sixties and, indeed, even the seventies, was Hans Herrmann. Originally touted as a new Grand Prix star, he was once as much a part of Mercedes-Benz’s legacy as he was a hero for Porsche. Having miraculously survived many spectacular accidents – his barrel roll in BRP’s BRM at Avus the most famous example due to it having been captured mid-action in a legendary Julius Weitmann photograph – he was nicknamed Hans im Glück (‘lucky Hans’), his 1971 autobiography wasn’t called Ich habe überlebt (‘I have survived’) for nothing. Indeed he survived a career spanning two of the most dangerous decades of the sport.

Now an octogenerian, Herrmann was born in Stuttgart, in 1928, close to the Solitude and right next door to where Mercedes was and where Porsche would end up. His parents owned two cafés which he, still as a youngster, took over right after World War II. His scholarship as a baker and confectioner, preparing to one day run his parents’ business, helped him to evade army duty – probably his first-ever act of survival. With the war over, it wouldn’t take long, however, before Hans would look danger straight in the eye as his passion for motorsport was slowly kindled. His first car was a pre-war BMW 328 acquired on the black market, but in 1951 this was swapped for a pukka Porsche 356A with which he started life as a privateer rally racer. His debut came in the Hessen winter rally, run in the night of February 9, 1952. His first class win followed soon, and it was in the prestigious ADAC-Deutschlandfahrt. As with all talented drivers, success came quickly. 1953 would see him become a works Porsche driver, taking part in national and international rally and sportscar events, while simultaneously starting a single-seater career in German F2 and making his Grand Prix debut in the German GP. At the end of the year his spoils included class wins in the Mille Miglia and Le Mans while he also grabbed the German up-to-1500cc sportscar championship, crowned by a win in the German sportscar GP. From being an amateur in 1952, he’d been running in the Eifelrennen and the Carrera Panamericana, with an offer under his to test-drive the new Mercedes-Benz 300SL. Say no to that!

Hans Herrmann leisurely awaiting the start of the 1953 German GP in his reworked Veritas-based Klenk Meteor.

There was more excitement in 1954, including a legendary survival act almost equal to that at the Avus in 1959. In the Mille Miglia, driving a 550 Spyder for Porsche, Hans was fast approaching a railway crossing. When he saw that the gates were closing for the fast train to Rome, he decided he couldn’t be delayed by it and slammed the throttle. It was too late to brake anyway. So by knocking the back of his co-driver’s helmet he ordered Herbert Linge – the later Porsche development chief – to duck for cover and raced his low-line Spyder underneath the rapidly closing gates. It was vintage chicken-with-madness, and Hans didn’t chicken out. Herrmann/Linge won their class and finished sixth overall. At the end of the year he used another 550 Spyder in the gruelling Mexican heat to finish third overall and win his class in the Carrera Panamericana.

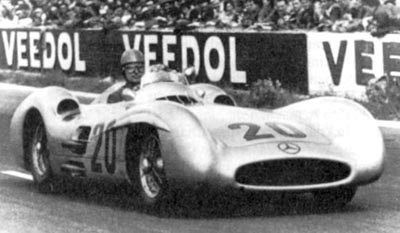

Now a part of a Mercedes-Benz factory gearing up for their Grand Prix debut, Herrmann pounded round the miles on the Solitudering and the Hockenheimring with the new W196, escaping from a huge crash at the latter circuit. At Reims, Hans had to play second fiddle to Fangio and Kling but still set fastest lap, becoming the youngest man to at that time having recorded such a feat. The rest of his Grand Prix season brought third places at Bremgarten and Avus, a fourth at Monza and a further retirement at Pedralbes. 1955 started off with the infamous Argentine GP, run in seering heat. With Kling and Moss both retiring their W196s, Herrmann had to give up his example for the pair to finish the race in fourth. Hans then switched to Mercedes’ sportscar team and their attack on the Mille Miglia. Driving as fast as the winning 300SLR of Moss/Jenkinson, Herrmann had to retire after losing his tank filler cap! Returning to Grand Prix cars, Hans suffered a crash with a major impact at Monaco, ruling him out for the rest of the season. While he convalesced from his injuries, Pierre Levegh took his place in the sportscar team for Le Mans – with tragic consequences… When Mercedes-Benz pulled out at the end of 1955, as a result of the Le Mans backlash, Herrmann was left without a works drive. Not for long, however, since Porsche was happy to take back their forgotten son. Starting the season at Sebring, Hans was teamed up with new boy Wolfgang von Trips, and the result was the inevitable class win. Back at home, Herrmann also grabbed the Solitude and German GP sportscar races to comfortably take the German sportscar title.

Hans was part of the Mercedes-Benz works effort that took Grand Prix racing by storm in the mid-fifties.

The two years following saw Herrmann at his most prolific. Having already tasted Italian cars by racing a Ferrari in the 1956 Targa Florio – the only time he ever drove a Ferrari – he signed up with Maserati to drive their sportscars in the Mille Miglia and at the Nürburgring. A one-off GP appearance at Monaco for the works team resulted in a DNQ. Meanwhile in Germany, a fall-out with Porsche management led to Herrmann leaving the team and switching his allegiance to Borgward, in order to compete in the European Mountain Championship. Using the Borgward RS he immediately took the championship’s runner-up position, before building on that success into 1958, winning at Aspern and taking third in the championship. However, 1958 was a sad year for Herrmann as well. His good friend Erwin Bauer, his co-driver during his very first rallies in 1952, died at the Nürburgring having already passed the finish line. Furthermore, his Grand Prix appearances in the ageing 250Fs of Scuderia Centro Sud and Jo Bonnier led to nothing. Still, a return to Porsche was getting nearer after a successful guest appearance at Le Mans, where he teamed up with Jean Behra to take the class win and third overall.

The BRP BRM is cartwheeling off the Avus track while Hans is on the tarmac counting his blessings.

A second period for the Porsche works started in 1959, when Hans was matched with Umberto Maglioli to become one of the second-string pairings. Their best result was a class win and fourth overall in the Nürburgring 1000kms. Meanwhile, Scuderia Centro Sud offered him a drive in their Cooper-Maserati for the British GP. The opportunity led to nothing but it kept his ties to the premier single-seater category alive. This was borne out when BRP offered him a drive in their BRM P25 for the German GP two weeks later. The venue – the dreaded Avus with its two long straights and its out-of-date high-banked Nordkurve – was hotly debated but the event went ahead all the same. Racing at speeds of over 280kph, drivers would be passengers in their tiny machines, while the banking was equally dangerous and daunting. So when on Sunday, approaching the slow Südkurve, Hans’s BRM suffered a monumental brake failure, people feared the worst when they saw the car cartwheeling off the track. Almost unstoppable, the car hit one of the strawbales and the impact sent the car into a frenzied nose-to-tail tumble. Hans was thrown out and lying on the tarmac he saw his car disintegrate into the distance. The famous Julius Weitmann picture went all over the world. While Hans was very fortunate to survive with bruises, his friend Jean Behra wasn’t so lucky. On Saturday, in the sportscar support race, the Ferrari reject lost control of his self-built Behra-Porsche on the steep banking and as the car slid wide it hit a concrete gun turret left over from the war. Jean was thrown out as well but his body slammed into one of the flag poles lining the top of the banking. He was dead at the spot.

Hans made an occasional appearance in the Behra-Porsche F2 in the 1959 Coupe de Vitesse at Reims, Carel Godin de Beaufort having taken over his Scuderia Ugolini 250F drive for the main event of the weekend, the ACF GP.

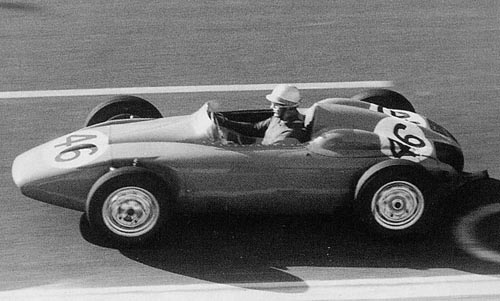

In 1960, Hans im Glück would be getting a lucky number to match his good fortune: 23. Now a Porsche works driver in both single-seaters and sportscars, he took an astounding overall win at Sebring in Bonnier’s 718 RS60, sharing with Olivier Gendebien, and then went on win the Targa Florio for Porsche as well, along with Jo Bonnier, at the same time co-driving Gendebien’s RS60 to third place! At the Nürburgring, teamed with Trintignant, he finished fourth in his No.23 RS60, and met his future wife… Two years later, he would get married to Magdalena, who was introduced to him by count Von Trips. The second half of the season Hans – and Porsche – shifted part of their attention to F2 racing, using the single-seater version of the 718. Several placings at the Solitude, the Südschleife, the Ollon-Villars hillclimb in Switzerland (in a Cooper-Climax), Zeltweg and Modena led to Herrmann’s first career F2 win at Innsbruck, while he finished the season with a hillclimb win, driving an RS60 at Schorndorf.

Hans in his 718 F2 trailing the similar RRC Walker example of Stirling Moss while leading Jack Brabham and Tony Marsh at the 1960 Flugplatzrennen at Zeltweg.

The success of 1960 was met with a downfall in 1961. Porsche decided to enter the new 1.5-litre F1 with their F2 machines but were comprehensively outclassed by Ferrari and the British teams. While Porsche worked on a V8 engine to replace its low-on-breath inline-4 Hans’s GP outings kept him at the back of the grid. In sportscars, a third place in the Targa Florio and 7th at Le Mans, sharing a Coupé-bodied RS61 with Edgar Barth, were his best results. Then shock came at Monza, where his good friend Wolfgang von Trips was killed. For a while he considered becoming a full-time road-car tester for popular German weekly Bunte Illustrierte, a cooperation he had started with journalist Helmut Sohre. Although he would continue to work with Sohre until 1975, motorsport kept beckoning – even if it wouldn’t be with Porsche proper. Now reduced to being a driver from the second drawer, Hans decided to throw his fate into the hands of Italian tuner Carlo Abarth. At first still linked to Porsche because of Abarth’s strikingly pretty GTL version of the Porsche 356 Carrera, he soon swapped to the Abarth works outfit altogether, competing in many endurance and hillclimb events while also acting as their factory test driver. In his four years for Abarth, Hans racked up no less than 25 class wins and 13 overall wins. His most successful Abarth year was 1964, with overall endurance wins at Avus, Enna, in the Nürburgring 500kms and the Coupe de Salon at Montlhéry, while in 1965 he took hillclimbs at the Raticosa, Mont-Ventoux, Aosta-Pila as well as the Wiener Höhenstraßenrennen.

During the time Hans spent at Abarth, Porsche had gone through quite a transition, as it stepped up its sportscar effort with the 906, later followed by the 910, 907, 908 and 914 models. With Ferdinand Piech at the helm of Porsche’s R&D, Hans was tempted to return to Weissach, joining Bonnier, Mitter, Davis, Glass, Glemser and Porsche’s trusty driver-cum-developer Herbert Linge, his partner in that infamous 1954 Mille Miglia incident. Joining Linge at Daytona, the re-united pair immediately took a class win and sixth overall. On a roll, Herrmann also took class wins at Sebring and Monza, finishing fourth on the road. Hans also shared with Linge at Le Mans, where they finished fifth, and second in class. His hillclimb season led to a long string of podium finishes before he took his first overall wins of the year, in the Austrian GP at Zeltweg and at Tulln-Langenlebarn.

Driving Porsche's 906 in the Spa 1000kms of 1966.

In 1967 Hans not only switched to the 910 follow-up, and to the long-tail 907 for the long-distance events, but he got a new team mate in Jo Siffert as well. Until he was switched to develop German youngster Rolf Stommelen during the course of 1968, Herrmann and Siffert formed a formidable pairing, taking no less than eight class wins, the highlights being the duo’s overall wins at Daytona and Sebring in 1968.

Having only had very few single-seater outings since his 1961 season, apart from one-off F2 appearances at his home races at the Solitude and the Nürburgring, Hans rejoined his friend Gerhard Mitter for the F2 race held concurrently with the F1 German GP in 1969. In practice, Mitter was dramatically killed and Hans decided to withdraw from the race. The following month he would be extremely lucky himself when he survived a massive crash in the Imola 500km race, barely without a scratch. That very same September month his son Kai was born. Hans im Glück indeed. Meanwhile, Porsche was dying for more overall wins and came out with the 917 beast, combining sheer power with Porsche’s lightweight alloy experiments. And a beast it was. At Le Mans, the brutal car was too much for privateer John Wolfe to handle, and the American was killed on the very first lap. Herrmann, driving a trusty 908 with Gérard Larrousse, suffered a heartbreaking defeat the next day. It looked like he was heading for a surprise win after all the faster cars had fallen by the wayside but he was beaten to line by 100m by Jacky Ickx’s GT40, the Belgian coming from behind to overcome what seemed an insurmountable lead for Herrmann.

In the 917 shorttail at Sebring in 1970.

Hans having been giving the duty of developing the 917, the already mythical car steadily grew into its all-conquering status, and was the car to beat in the 1970 world championship. With Porsche entrusting its sportscar effort to JW Automotive and Porsche Salzburg, Hans was matched to Richard Attwood in one of the second-string Salzburg cars. The death of his friend Mitter and the birth of his son Kai had pushed Herrmann into contemplating retirement, as he also grew weary of the sport’s increasing commercialism. Having missed out so nearly in the 1969, he was tempted by his wife Magdalena to call it quits if he would win Le Mans this time out. He agreed right before climbing into the 917.

Lucky No.23 racing to a positively career-ending victory at Le Mans in 1970.

The Herrmann/Attwood car wasn’t among the favourites to win – Herrmann’s car actually almost never was – but after so many years having had to go without it lucky Hans was given the No.23. Two hours into the race, the Salzburg Porsche was no more than a midfield contender but fortune intervened. A freak accident involving a slower Alfa eliminated all four Ferrari 512Ss while the two JW Porsches were out at half-distance, with the Piper Porsche heavily delayed by numerous pit stops. So by 4 AM the Herrmann/Attwood car walked into a lead that it was never going to give up. 12 hours later Porsche had taken its first Le Mans overall win. Hans kept his promise to Magdalena and offered his resignation to the Piech family. Only after Hans was able to lure Denny Hulme into replacing him did the Piechs allow him to get out of his contract prematurely. Herrmann wasted no time in setting up a car-parts trading company, Hans Herrmann Autotechnik. He is still seen at historic motor racing events today.

A true Porsche lynchpin

Herrmann’s 1966-’68 driving partner at Porsche, Jo Siffert, was now at the height of both his fame and his powers. Having become part of the glorious JW Porsche 917 effort, ‘Seppi’ was swapping honours with team mate Pedro Rodriguez for most amazing sportscar driver of the moment. The moustachioed Swiss had come a long way. In Formula 1, he had been a hard-trying back-of-the-grid privateer for years before becoming a giant-slaying privateer after his astonishing win in the 1968 British GP, after a long drought returning privateer team owner Rob Walker to the winners’ circle for the very last time. In sportscars, his deal with Porsche to join their class-winning efforts placed him ideally for Zuffenhausen’s later overall attack on the World Sportscar Championship. And when Jo showed he could do the business in F1, it was only logical to match him with Brian Redman and put him in one of the lead 917s.

By then, Jo was well into his thirties but in his early twenties, he started out on motorcycles. Ever since his childhood, when his father brought him along to the Swiss GP at Bremgarten, he wanted to be a racing driver, and this was the next best – and cheapest – thing. He had been a terrible student and only started to learn when he was introduced to a nearby body shop. The owner allowed him to work and study at the same time, and Jo suddenly found a purpose in life. In 1956, he met local bike racer Michel Piller and the two soon formed a duo, travelling across Switzerland and Europe to contest 125cc and 350cc events. Siffert’s national 350cc title in 1959 led to his realizing his dream by switching to four-wheel competition. After acquiring a front-engined Stanguellini Jo and Michel – now acting as his mechanic – joined the continental Formula Junior circus mid-season at the Lotteria GP at Monza. The race was won by later Porsche team mate Colin Davis, ahead of Henri Grandsire and a young Denis Hulme, racing on his New Zealand scholarship programme. Jo finished an inconspicuous 19th, led by numerous no-name Frenchmen and Italians, including one Giancarlo Baghetti. The results soon picked up, however, culminating in a fourth at Messina, only headed by Davis, Hulme and Baghetti. In August he switched to hillclimbs and did very well, a second in the Swiss GP at St. Ursanne-Les Rangiers his best result. Armed with a Lotus 18, still self-run but with Jean-Pierre Oberson as a second mechanic, things went even better in 1961. A lot better, in fact, helped by a switch to a Lotus 20 by the time the Swiss threesome headed out to the Nürburgring for the famous Eifelrennen. By that time, Jo had already won the Mont-sur-Rolle hillclimb, the Cesenatico GP and the Garda GP at Salò. The Eifelrennen would be his as well, followed by a fifth in the Monaco GP support race, a third at the GP des Frontières at Chimay and a fourth at Rouen. The only blip was 9th on a British excursion to Oulton Park. Having placed third in the 2-litre class with Sepp Liebl in a Ferrari Testa Rossa in the Nürburgring 1000kms – his first-ever sportscar race – Jo merrily continued his good form by winning at Terramo, Enna, Cadours and Montlhéry and the Mont Ventoux hillclimb. His win at the Paris venue came only after the team suffered a terrible accident on the way there, damaging the Lotus 20. Remarkably, in only his second year of racing, the privateer Siffert had won the European Championship, tied on points with the Tyrrell-run South African Tony Maggs.

For 1962, Seppi was duly picked by Scuderia Filipinetti for their Formula Junior assault and he delivered by winning at Cesenatico and Vienna. However, it was obvious for all to see that Siffert had outgrown the Juniors and was ready for the big time. He soon discovered that there were different laws ruling over Grand Prix racing. In this world, privateers fighting for outright victory had quickly become obsolete, with the exception of the remarkable Rob Walker and the even more remarkable Stirling Moss. While his 1961 co-champion Tony Maggs had a works Cooper contract and was already scrapping for points finishes, Jo had to discover life as a Grand Prix driver the hard way. This meant a DNQ in his first GP attempts at Naples and Monaco, even though the latter was caused by the ACM’s quirky qualifying rules that gave precedence to works drivers Ginther, Taylor, Bonnier and Maggs. Switching between Filipinetti’s Climax and BRM engine Jo was generally found at the back in his Lotus 24, although he managed a fourth in the Mediterreanean GP at Enna and won two Swiss hillclimbs. The non-championship races were his opportunities to show his talent and after surviving a huge shunt in the early-1963 Lombank Trophy at Snetterton he finished second to Jim Clark at Imola and won at Syracuse. Things were not well with Filipinetti, however. Michel Piller had already left the team at the end of 1962, and ahead of the Monaco GP Jo decided to unilaterally break the ties with the Swiss team, buy their Lotus 24, their two BRM and Climax engines and go it alone. It would still be a year of frustation, a sixth and a single World Championship point at Reims the only reward for the huge financial risk he put himself into.

Another breakdown for the Walker Cooper-Maserati, as Jo pensively wonders about his luck at Zandvoort.

In 1964, Jo initially ploughed on with his increasingly outdated 24, having already ordered a BRM-engined BT11 with Jack Brabham, along with a Cosworth-engined BT10 F2 car for the new Formula 2 series. The season didn’t start as well as he’d hoped for, as he broke his collarbone with a big crash at Syracuse, the scene of his win a year ago. Fortunately, the car was only slightly damaged, which was a good thing, since the BT11 wasn’t ready to race until Zandvoort. Helped by Oberson and his new second mechanic Heini Mader, who would go on to become a famous engine wizard, Jo and the BT11 gradually got up to pace, up to the point that he took a splendid fourth at the Nürburgring. On a roll, he set fastest time in practice at Enna. A non-championship race, yes, but he beat Clark’s works Lotus and Ireland’s BRP to the pole, repeating his form on the Sunday, fending off the two Brits across the line. He would copy the trick one year later. At Watkins Glen, Siffert took his first podium in a World Championship, helped by Jim Clark (in Mike Spence’s car) running out of fuel.

Would this result mean a works drive for 1965? Not quite, but he did join up with Rob Walker as a team mate to that other Jo, Bonnier. This meant that he would still only be fighting for small-points finishes, and he did so with sixths at Monaco and France and a fourth late in the season in Mexico. His best shows would again be in non-championship events, most prominently so in the Syracuse GP, in which he battled with Surtees for the lead until he had to retire with electrical problems. Two weeks later however, in the Sunday Mirror Trophy at Goodwood, Jo almost killed himself when he vaulted the chicane barriers. Miraculously, he survived with a mere broken ankle. Even more miraculously, he recovered in time for the Monaco GP to finish the 100 laps and multiple thousands of gearchanges. At the start of 1966 he gave the ageing Brabham its best possible goodbye by taking second in the South African GP. He will have remembered the car lovingly during his plight with Walker’s new Cooper-Maserati. Plagued by the V12’s poor reliability Jo had to wait until Watkins Glen before he crossed the line for once, in fourth. He did use the Cooper-Maserati to once again win the St. Ursanne hillclimb, though, as he had done in 1965 as well.

Jo fending off the attentions of Chris Amon in his victorious 1968 British GP.

Meanwhile, Siffert had been gradually getting acquainted with sportscars. In 1964, he shared a Porsche 904 with Heinz Schiller in the Nürburgring 1000kms and the Reims 12hrs, and competed in the Tour de France with David Piper’s GTO. A year later he tried his hand at Le Mans, sharing a Maserati with Jochen Neerpasch, but now he was getting more serious, having teamed up with Charles Vögele to regularly race his countryman’s Porsche Carrera 6. Jo got quickly noticed by Baron Huschke von Hanstein, the Porsche team boss, who got him a works Le Mans drive alongside Colin Davis. The pair were right on the money, taking fourth overall, the 2-litre class win and the Performance Index. It was a great start to a flourishing career as a Porsche sportscar driver. Indeed, he was matched up with Porsche returnee Hans Herrmann in 1967. The two won the Performance Index at Le Mans, finishing fifth, and finished well up the order at Daytona, Sebring, Spa, Monza and in the Targa Florio. Jo’s concurrent F1 career remained in the doldrums, however, with the Walker Cooper-Maserati still proving troublesome. Third places in the Race of Champions, the International Trophy and Syracuse were the usual non-championship awards but the championship events itself garnered just two fourths in the French and US GPs. His works BMW F2 drive was equally unsuccessful, even though he used the T100 to continue his subscription on victory in the St. Ursanne-Les Rangiers hillclimb at home.

You could argue that Siffert’s works Porsche programme formed the most important chunk of his full 1968 diary. Wins at Daytona, Sebring and the Nürburgring, followed by victories in the more minor sportscar events at Hockenheim, Enna and Zeltweg would certainly suggest so. Still, the overriding memory of the year must be Seppi’s victory in the British GP. And to imagine that a garage fire almost put paid to that. Early 1968, Rob Walker and Jack Durlacher had done a deal with Colin Chapman to take over the ex-Jim Clark Lotus 49. Could the team finally return to their glory days with a Lotus chassis? However, practising for the Race of Champions, Jo went off in a big way, almost destroying the car. The heavily damaged monocoque was transported to the team’s base in Dorking, and to everyone’s amazement, the garage burned down to the ground that very night, and the Lotus with it. Walker pleaded with Chapman for another car, and with the help of everyone at Hethel a Tasman chassis was converted to Grand Prix spec. Initially, the team ran into all sorts of trouble with the car, ranging from transmission to diff to oil pressure problems. In France, Jo finally finished a race but in 11th place, 6 laps down. It all changed on July 20, at the same venue that had led to the destruction of the team’s first 49. After putting the Lotus fourth on the grid, he battled with Chris Amon’s Ferrari all the way to the flag to give the Walker and Lotus combination its first World Championship win since Moss’s famous 1961 Monaco victory. Siffert’s victory is usually seen as the last by a privateer team, but that’s discounting the many victories Jackie Stewart took in Ken Tyrrell’s private Matra and March entries.

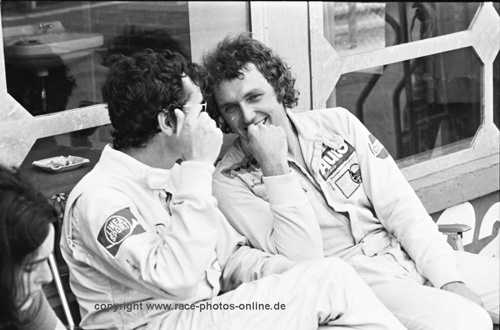

In the pits with Porsche's 908 during the 1968 Le Mans event.

The Brands win – and his extremely successful sportscar season with Porsche probably as well – finally put Siffert on the map with the leading Grand Prix teams. In fact, none other than Ferrari offered Seppi a Grand Prix and sportscar contract for 1969. Yet Jo saw the importance of his Porsche programme and wanted to stay with the Germans. This meant that he agreed to stay with Walker and Durlacher for another year while aiming for outright sportscar glory, knowing that Porsche’s 917 big gun was waiting in the wings. It wasn’t a bad choice at all. While Ferrari suffered a disgraceful Grand Prix season, Jo took a second at Zandvoort, a third at Monaco, a fourth at Kyalami and a fifth on the Nürburgring, finishing ninth in the World Championship. And although his sportscar season got off to a bad start with retirements in the two American endurance classics, Jo and his new team mate Brian Redman quickly picked up the pace back in Europe, winning the Spa, Monza and Nürburgring 1000km events, as well as the Watkins Glen 6hrs, at a very early stage handing the World Sportscar Championship to Porsche – even though the Germans very narrowly lost out at Le Mans. So in summer, Weissach switched Siffert to Can-Am to join the North American big-banger championship mid-season with their Porsche-Audi conversion of the 917, running under the supervision of John von Neuman, Richie Ginther and Rico Steinemann. There was no way to beat the Bruce and Denny Show, however, and the No.0 Porsche was left fighting over the breadcrumbs with Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney, Chuck Parsons, George Eaton, Peter Revson and team mate Tony Dean.

The 1969 title had been won still using the 908/02 but Siffert – teamed up with Kurt Ahrens Jr for the occasion – had already given the 917 a victory by winning on the Österreichring. In 1970 however, the 917, now run by JW Automotive and Porsche Salzburg on behalf of Porsche, would be in a class of its own, even though it now faced stiff opposition from Ferrari’s equally monstrous 512S. Siffert again teamed up with Redman, with Pedro Rodriguez and Leo Kinnunen in JW’s other famously Gulf-liveried car. The latter duo did most of the winning, but Siffert and Redman took the Targa Florio (albeit in the small 908) and the Spa and Zeltweg 1000km races, while Redman also shared the winning car at Daytona. This pattern continued in 1971, Rodriguez (now with Jackie Oliver) being the absolute star, with Siffert (now with Derek Bell) usually ending up in second place, apart from the new duo’s best possible start to the season by virtue of victory in the tragic Buenos Aires 1000kms. And if it wasn’t for Rodriguez, the Alfa efforts of Andrea De Adamich cum suis and the Martini Porsche pair of Elford/Larrousse would also interfere for the wins, while their team mates Helmut Marko and Gijs van Lennep took the big one. Still, the overall impression was that had Porsche put the Mexican and the Swiss in the same car the competition would only have seen the Kurzheck when it would lap them. In the second half of the season, the World Sportscar Championship signed, sealed and delivered on the Weissach doorstep, Jo travelled to North America to return to the Can-Am championship in an STP-liveried 917/10 spyder built by Edi Wyss and Hugo Schibler, taking on what was now the Hulme and Revson Show. He was unable to beat the McLaren stranglehold, however, and on the only occasion both M8Fs faltered, on the Mid-Ohio sportscar course, it was Jackie Stewart who comfortably beat the Porsche in Carl Haas’s Lola-Chevrolet T260.

Vic Elford leading Seppi in the 1970 Le Mans edition that would be won by Hans Herrmann.

At the same time, Jo’s single-seater career was moving along well. Even though he probably made a mistake to join March in its first year he still showed enough to be signed by BRM for 1971. To be fair, it wasn’t entirely his choice, since Porsche wanted to prevent Jo from accepting another Ferrari offer, so they bankrolled his Grand Prix drive with March. The March was an excellent car, as was shown by its huge early-season potential, especially in the hands of Jackie Stewart, but it was a cash-strapped quick-and-dirty solution as well. If Siffert had stayed put he would have had the car with which Robin Herd really showed what he could do when the time and the money was there: the March 711 driven to second place in the 1971 championship by Ronnie Peterson. Meanwhile, Jo’s BMW F2 programme finally paid dividends with a win in the 1970 Rouen F2 race and a second place at Enna. A early-1971 excursion to Colombia gave Seppi another F2 win when he took the Colombian GP driving a Chevron B18.

In a P160 T-car sometime during 1971.

His decision to join his Porsche team mate Rodriguez at BRM in 1971 looked unwise, given the P160’s early form and Peterson’s second position in the intermediate standings, but a second Grand Prix victory finally came in the Austrian GP. And it was no win by attrition in an other Tyrrell-dominated season. Siffert took pole and fastest lap as well, and eventually beat Fittipaldi to the line by five seconds with a left-rear tyre that held almost no air at all. Jo rounded off the season with second place at Watkins Glen, where he always did well, to finish a joint fourth in the championship, his best F1 season to date. To celebrate, he duly took pole for the World Championship Victory Race at Brands, Rothmans’s idea of an end-of-season racing bash. The party turned into tragedy, however, when Siffert’s BRM ran off the circuit on lap 15, burying itself in the earth banking and catching flame. Seppi had no chance of survival. He was later absolved from any suspicion of driver error when it was found that his suspension had been bent by his poor getaway at the start and the resulting contretemps with Ronnie Peterson’s March, pushing him on the grass. 35 years was too short a life for such a brilliant sportscar driver and underrated Grand Prix driver.

Fun comes first

At the time ‘Seppi’ died young Jochen Mass was nothing but a hillclimber and touring car driver looking forward to his big break with Ford in the ETCC. In 1972, he would be part of the Capri RS line-up that shook the championship in 1971, taking all but two wins and handing Dieter Glemser the drivers title. Glemser would be back, teaming up with Alex Soler-Roig and Hans Stuck, while Mass was paired with Gérard Larrousse for the long-distance races. Opposition would only come from the Schnitzer and Alpina BMWs. Young Jochen made his presence known at once by winning at Monza while Glemser won the next two races at the Salzburgring and Brno. A rare Ford defeat (and the only one during the season) followed in the Nürburgring 6hr race, with Fitzpatrick, Heyer and Stommelen winning for Schnitzer, but Mass and Larrousse at least finished in second position as the two other Capris of Glemser/Stuck and Soler-Roig/Bourgoignie/Birrell hit trouble early on. With Stuck switched to the Mass car for the Spa 24hr classic, the two formed un unbeatable pairing as they led home Bourgoignie/Birrell and Glemser/Soler-Roig by five laps. This time, BMW never had a look in. At Zandvoort, it was the Mass/Larrousse car’s turn to break down but Ford switched Mass to the Glemser/Soler-Roig car to have him cover just enough distance to share in the win points-wise. At Paul Ricard, the works cars missed a beat but the private Capri of Muir/Miles still won for Ford, leading guest stars Stewart and Cevert, while it was now obvious that Ford of Cologne was backing Mass for the drivers championship. Initially teamed with Glemser he was put in the surviving Soler-Roig/Larrousse car to still claim third. Mass and Larrousse won again in the season-closer at Jarama, where hometown hero Soler-Roig joined them when Glemser was left stranded out on the circuit with a broken fuel pump.

A still very boyish Jochen Mass relaxes during the 6 Hours meeting at the Nürburgring in 1972.

(photo Rudolf Schoettel, used with permission)

Even though Jochen had done a small number of F2 races during 1972, as an occasional third driver to Lauda and Peterson’s works March effort, he could well have remained the typical seventies touring car star, not unlike Toine Hezemans, Dieter Quester, Hans Heyer or John Fitzpatrick. The offer to join the Surtees F2 team proved irresistable, though. Make no mistake, Jochen still played his part for Ford in what would a barnstormer of an ETCC season, BMW having ramped up their efforts, with the regulars being joined by Grand Prix stars such as Lauda, Amon, Hunt, Ickx and Pescarolo. Mass was paired with the likes of Jody Scheckter, Jackie Stewart and John Fitzpatrick but mostly Dieter Glemser, and with the latter he won at Mantorp Park. Most of the other races were won by either the works BMWs or those run by Alpina, leaving Hezemans the undisputed champion.

The F2 season proved to be much more successful for Mass. Even though there was no stopping Jean-Pierre Jarier in the works March-BMW, Jochen’s swap to the Surtees team joining Derek Bell and Surtees’s graded F1 drivers Mike Hailwood and Carlos Pace finally proved wise when his season eventually got on song with a win at Kinnekulle, the sixth round of the European championship. A string of second places at Nivelles, Rouen and Mantorp Park followed, along with another win at Hockenheim. A third at Enna lifted him above Patrick Depailler in the standings, allowing him to finish runner-up to runaway champion Jarier. His great form was rewarded with a GP debut at Silverstone, in a third Surtees TS14A. Jochen performed admirably in practice, qualifying one place ahead of team regular Pace, but the three Surtees cars were all wiped out in the infamous Woodcote mayhem instigated by Jody Scheckter. Mass returned to the F1 at his home race at the Nürburgring and in the season-closer at Watkins Glen, on both occasions qualifying in the midfield and running close to the points in the race. It was only logical to promote Jochen to the F1 team full-time in 1974 and the year started off well with a fourth in the non-championship De Medici GP in Brazil and a fine second in the International Trophy. However, the new TS16 proved to be a very difficult beast, and the German walked out of the team after his home event, angered that a fine performance had yet again been nibbed in the bud. It was a blessing in disguise since the two North American races at the end of the season gave Jochen another third-car opportunity, this time in the vacant Yardley McLaren. Now he was with a well-run team that was about to celebrate its first driver championship through the hands of Emerson Fittipaldi.

ETCC heydays: Ford versus BMW.

In his first full season with McLaren, replacing Denny Hulme, Mass was understandably overshadowed by the Brazilian World Champion but Jochen still managed to take three third places and that win – or ‘half a win’ – at Montjuich. The trouble in the early part of his first year had been his poor qualifying form, as he usually trailed Fittipaldi by half a second up to a full second, forcing him to fight his way up the field. At Paul Ricard however, Mass managed to outqualify Emerson for the first time, and translated that newly found form into a very strong race, not just by beating Fittipaldi, but also by being in contention for the lead until the very last lap. In the end he finished third behind Hunt and winner Lauda, just two seconds behind the Austrian. Finishing seventh in the championship, shared with Scheckter, wasn’t bad at all, and all eyes were focused on 1976. Could the German take over from Fittipaldi who was leaving to join his brother’s team? How would he stack up against new boy James Hunt?

At this moment in time Mass was still a long way away from being the Porsche sportscar mainstay that he is mostly known for. In fact, in an age when two-timing between single-seaters and sportscars was still de rigueur, he wasn’t even a sportscar driver as such. Yes, he had done a few sportscar races when Ford Germany entered their Capris in the touring-car class of their home event at the Nürburgring, and also at Le Mans, but it wasn’t until 1975 – ironically his first year at the top of his single-seater game, and also of his only Grand Prix win – that he seriously joined the sportscar trail. At first, Mass lined up with the Gelo team that he already knew from his German touring car days, sharing a Mirage-Cosworth GR7 with Aussie Tim Schenken, but halfway through the season he swapped to the Willi Kauhsen-run Alfa team, subbing for Jacques Laffite, who was busy winning the F2 title. Joining Arturo Merzario in the No.1 T33/TT/12 he had immediate success when the pair won the Coppa Florio at Enna. When Kauhsen ran a third car at the Nürburgring he joined the team again, and partnered with Jody Scheckter they scored a sixth.

In 1976, however, Mass would be a works Porsche driver. On the very first occasion of his legendary partnership with Jacky Ickx the two were victorious. With prototypes now running into a bit of a dry spell, these would become the heydays of Group 5 racing, and Porsche was fielding the monster: the striking Martini-liveried 935 tubeframe silhouette. Mass and Ickx won at Mugello, then at Vallelunga, had to cede to Stommelen/Schurti at Watkins Glen, but won again at Dijon to easily clinch the title. Meanwhile, in the now separate prototype championship there were more wins for Mass at Monza, Imola, Enna (with Stommelen) and Dijon and the Salzburgring (in a solo run). These occasions saw the arrival of the open-top 936, and the pair beat Renault’s new A442 prototype and Alfa’s ageing T33. Jochen missed out on the Le Mans win when Ickx was paired with Van Lennep, but it had been a season of total Porsche domination – and it wouldn’t be the last.

In the stunningly liveried 1975 M23 at Monaco.

Jochen’s 1976 Grand Prix season was a huge disappointment, though. Totally eclipsed by Hunt, Mass had just two thirds at Kyalami and Zeltweg to account for, plus a handful of minor placings and a missed opportunity at the Nürburgring because of Lauda’s fiery accident, leaving him ninth in the World Championship standings. Instead of moving up, he was going down. Still, he stayed on for a further season, backing up his now World Champion team mate, but a second place at Anderstorp, helped by Andretti running out of fuel on the last lap, was his best result. Two graded F2 guest appearances for March in the Jim Clark Memorial at Hockenheim and Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring were converted into wins, though. Nevertheless, the Montjuich win would remain his sole moment of ultimate F1 glory, since Tambay’s arrival at McLaren meant that Jochen had to look elsewhere. In Johansson/Kovalainen style, Mass decided to join a backmarker team, hoping to reinvent his Grand Prix career. He could have done better, though, than to go with the German ATS team run by autocratic wheel magnate Hans Günter Schmid. His miserable season ended prematurely with a severe testing accident at Silverstone. A recovered Jochen switched to Arrows in 1978 to stay at the Warsteiner-sponsored team for two seasons, and only shone on occasion, for instance when he took fourth at Monaco in 1980, and the year before when he was third at the principality until brake problems intervened. After a season out in 1981, he rejoined the F1 circus for one more team but his spell with the Rothmans-backed second March incarnation was a disaster and finished prematurely when he spun off on the tenth lap of the French GP while lying in 18th position. It was a sorry end to a life in single-seaters that had started off with so many promises. Looking back it’s hard to avoid the impression that it could have reaped much more fruit.

Mass in sportscars in 1977 was another matter. Still with Ickx (and on occasion Jürgen Barth), and Group 5 still in a separate championship with GT cars, Jochen was the fastest man on track on almost every circuit, in easily the fastest thing around. No other Group 5 car had as much as a look-in, and in turn the Martini cars were simply better than the customer versions run by the likes of Kremer, Gelo, Moritz and Jolly Club. An accident kept Mass and Ickx from winning at Mugello while a fuel injection problem halted the two at the Nürburgring, but they won everywhere else. Meanwhile Alfa was left as the only manufacturer still present in the prototype championship and when they pulled out at the end of 1977, the prototype class was dead and buried. Many of the privateers continued in the European Sportscar Championship set up for 1978 but the World Sportscar Championship would be all about Group 5 and GTs. The Porsche works was only present at Silverstone, however, where Ickx and Mass duly led home Kremer’s Wollek and Pescarolo by seven laps, but Weissach elected to focus on Le Mans instead. It became a deception when Renault stole Porsche’s march, handsomely beating two 936s while the Ickx/Mass/Pescarolo 936 retired after four hours. It was the same story in 1979, with the factory only appearing at Silverstone, Mass teaming with Redman but crashing out in the final hour.

Still enamoured with the 935, and now without a Grand Prix drive, Mass joined the Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft in 1981. Sportscar and touring car racing all around the world was at the lowest ebb history had ever seen, but the DRM was still keeping up appearances. Over the years, Jochen had done the occasional guest appearance in the DRM but his employment with Joest Racing was intended to be full-time. He came second at Zolder and the Nürburging and won at Hockenheim but after that the Joest 935 went out of sight, only to return with third place in the August round at Hockenheim and fourth in the September round at the Nürburgring. Mass still finished fourth in the championship, since there were only about six Group 5 silhouettes each left in each of the two DRM divisions. At Le Mans, in the 936’s swansong race, Mass finished twelfth, the Mass/Ickx pairing now split up, the Belgian hooking up with Derek Bell while Mass was sat in the Schuppan/Haywood car. Ickx and Bell won.

Blending the 935, Capri Turbo, M1, 320i Turbo and Lancia Beta Montecarlo into a poisonous brew of extremely wide-bodied vehicles, the DRM had been a monumentous crowd-puller in Germany but into the eighties the entry numbers started to dwindle. Germany and the rest of the world was anxiously awaiting the new Group C, and it was no wonder that DRM immediately adopted the new rules for 1982. The now Rothmans-backed Porsche factory made a single DRM appearance in the Norisring jewel-in-the-crown race, which Mass duly won, narrowly beating Winkelhock’s Zakspeed Ford C100, but the main interest was with the revived World Sportscar Championship and Le Mans. In the historical one-two-three for Porsche at the Sarthe, Mass took second with Schuppan before a renewed partnership with Jacky Ickx gained him wins at Spa and Fuji. In 1983, wins followed at the Nürburgring and Spa, but Mass missed out again on a Le Mans win that would remain elusive for quite some time to come, while the Bell/Bellof partnership generally proved the faster of the two factory 956s. It was the same in 1984: Ickx and Mass won at Silverstone and Mosport Park, but the mercurial Stefan Bellof usually had the better of them. The 1985 season started well with wins at Mugello and Silverstone but fastest lap was again the only honour that Jochen took home from the Sarthe. After Le Mans, the second factory 962C got the upper hand and eventually Bell and Stuck took the title. A victory in the season-closer at Shah Alam wasn’t enough to offset the Bell/Stuck mid-season run. In all, Mass took eight WSC wins between 1982 and 1985 yet never emerged with the drivers title first instigated in 1981. Ickx’s better luck at Le Mans, where Jacky and Jochen were invariably split up to hedge Weissach’s bets, made the Belgian the sole champion in ’82 and ’83 while the No.2 Porsche was the most successful in ’84 and ’85.

This was amplified in 1986, when Jochen got a new team mate in Bob Wollek and was dealt all the bad cards. Now facing pressure from Jaguar, Sauber-Mercedes and several Porsche privateers upping their game, it was no longer a foregone conclusion that a Rothmans Porsche suffering ill fortune would still finish second. This became even more apparent in 1987 when Jaguar usually had the beating of Porsche. So when the German marque still won Le Mans – with Jochen in the car that got into trouble, of course – they wisely pulled out, leaving Bell, Stuck and Wollek to swap to Joest and Mass to join Oscar Larrauri at Brun Motorsport for the remainder of the season. Brun’s 962C was no match for the XJR8, however, and two third places at the Nürburgring and Spa, in the wake of the Jags, were the best results Mass/Larrauri would harvest.

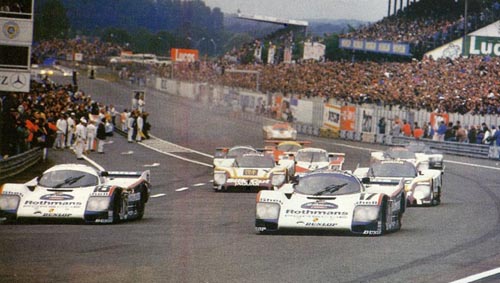

Another missed opportunity: the start of the 1987 Le Mans 24 Hours.

A change of seasons brought a change of teams. Jochen Mass was now no longer a Porsche driver. In the winter of his career, the highly experienced German chose to join the up-and-coming Sauber-Mercedes for one last attempt at all-out sportscar glory – i.e. a win at Le Mans. It was a timely switch. Sauber’s C9 in ’88 spec was almost on a par with Jaguar’s new XJR9 and it looked like the 1988 championship would be a cracker, especially when Mass, Mauro Baldi and Jean-Louis Schlesser won at Jerez on behalf of the Swiss-German cooperation. At Jarama, however, Martin Brundle and Eddie Cheever turned the tables for Jaguar, beating Mass and Schlesser by 20 seconds, repeating the trick at Monza and Silverstone. At Le Mans, Lammers/Dumfries/Wallace famously took the first British win on the hallowed French soil in ages while Sauber-Mercedes suffered the embarrassment of a full withdrawal. Mass/Schlesser struck back in the short race at Brno, and also won at the Nürburgring. Since Brundle had been switched to the winning Nielsen/Wallace car at Brands Hatch and was partnered with Jan Lammers at Spa, where Baldi and Stefan Johansson won for Sauber, the Brit now held a healthy lead that was increased by another Brundle/Cheever at Fuji. A Sauber one-two at Sandown, Mass/Schlesser heading Baldi/Johansson, wasn’t enough to stop Brundle from taking the drivers title back to Britain.

In the new 480km format for 1989, however, the Sauber had the legs of Jaguar’s XJR11. In fact, the ageing Porsche 962C was suited better to these circumstances than the Jags, and often the Joest, Brun and Kremer Porsches offered the stiffest competition to the dominating Saubers. In the end, Mass/Schlesser won at Jarama, the Nürburgring, Donington Park and Mexico City to comfortably seal the title for the Frenchman, who started the season off with a lead by joining Baldi at Suzuka. So the drivers title eluded Jochen again – and he would never come any closer – but he finally tasted the sweets of victory at Le Mans when the Mass/Reuter/Dickens beat the sister car of Baldi/Acheson/Brancatelli by five laps, with Schlesser/Jabouille/Cudini only fifth in the pole-winning C9/88.

The following year, Mass would contribute to a legacy for the nineties and beyond. As Mercedes ramped up their factory backing following such a successful season, the new Sauber C11s became known as Mercedes-Benz. With one eye already on F1, the sportscar programme would provide the ideal breeding ground for the Stuttgart firm’s junior drivers. So Mauro Baldi was moved to the lead car, freeing old-hand Mass to tutor the youngsters. While Schlesser and Baldi won most races, Mass managed to beat them twice, at Spa with the help of Karl Wendlinger, and in Mexico while partnered by Michael Schumacher, even though he was helped by the No.1 running into trouble on both occasions. Schlesser and Mass were back together for 1991, but so were the Silk Cut Jaguars, while Peugeot debuted strongly in a world championship that was being strangled by the oncoming 3.5-litre rules. The new unloved Mercedes C291 won only once in 1991, at Autopolis, and perhaps it was only natural that Schumacher and Wendlinger were the ones who did it. They were the ones looking forward to F1 while Jochen was probably looking forward to retirement. He’d been everywhere, seen it all, done it all. Racing would have to be fun in the first place – perhaps that’s why he is still a regular star in the Goodwood Revival Meeting.

The Mercedes C11 at the 1999 Goodwood Festival of Speed. (photo 8W)

Overriding memory

Hans Herrmann, Jo Siffert and Jochen Mass were never champions, and of the three only Herrmann and Mass won Le Mans – and only once. They are known for achievements other than those performed in the service of Weissach, such as Herrmann’s hillclimbing titles and the Grand Prix victories by Siffert and Mass at Brands Hatch and Montjuich. Still, the overriding memory of this trio is as seen racing a Porsche sportscar to great effect, be it an RS60, a 917 or a 956, power on, awe-inspiring, hammer and tongues through Brünnchen or Eau Rouge.