1992 Indianapolis 500

An Indy record deliberately listed incorrectly

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- May 10, 2016

Related articles

- 1995 Indy 500 - Rough justice, but justice nonetheless, by Henri Greuter

- 1996 Indy 500 - The 239.260 car, by Henri Greuter

- Penske-Mercedes PC23-500I - Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park, by Henri Greuter

What?Galmer G92 Where?IMS Museum When?Indy 500 100th Anniversary Exhibition, 2011 |

|

Why?

Commemorating the 100th Indy 500 that is about to take place later this month, 8W looks at a remarkable story from one of the 99 races held up to this date. Even though we chose to focus one of the commonly known records it is one that is in fact incorrect, and kept incorrect for good reasons. The 0"043 gap between winner Al Unser Jr and second-placed Scott Goodyear is the closest finish ever recorded at the Speedway in a 500-miles race. The actual difference, however, is even smaller than that. IMS and USAC have on at least one occasion acknowledged that this is the case but generally prefer to leave this fact unknown to all, especially being secretive about the cause.

Since 1988, Lola dominated the starting fields at Indianapolis but between 1988 and 1991, they were victorious only once: in 1990, with Arie Luyendijk. By 1992, though, Lola had practically become the sole manufacturer of customer Indycars. Penske only sold its previous model and kept the latest model for themselves while Truesports was new in the business, having debuted in 1991, and an unknown quantity. Lola, on the other hand, was a cooperative partner when teams were looking for a customer chassis. As late as 1990, Kenny Bernstein Racing and Menard Racing had been using Buick V6 engines, fitted in Lola chassis of at least one year old. Those cars had been converted to Buick power in the USA, the Lola factory had little if anything to do with such efforts.

Jim Crawford in his 1990 backup car, a '89 Lola-Buick. Rule changes effective from 1990 had a negative effect on just about any pre-1990 chassis being competitive against the 1990-built chassis. Crawford was one of the many also-rans that year but literally provided the high point of the year with his primary car earlier that month! (photo HG)

Ever since Buick's appearance in 1984 with their V6 engines, there had been only a handful Indy attempts with engines in the latest type of chassis. The most notable occasion came in 1985 when Pancho Carter and Scott Brayton qualified March 85C-Buicks on the front row. From then on, Brayton was the only driver for whom brand new chassis (initially March, later on Lola) fitted with Buick engines were entered between 1986 and 1989. All of these cars had been taken from the production line and were modified for the Buick in the USA, they were not redesigned by either March or Lola to fit the Buick engine. But that changed in 1991.

For 1991, Bernstein and Menard contacted Lola with the request to produce a reworked version of their 1991 car, optimized for use with a Buick V6. Lola accepted the orders and built a series of dedicated Buick chassis. These cars proved to be the fastest-ever Buicks in practice, one of them ending up as the fastest car in the field, only missing out on pole due to it being a second-day qualifier. Race day reliability of the Buick engine, however, remained its main weakness.

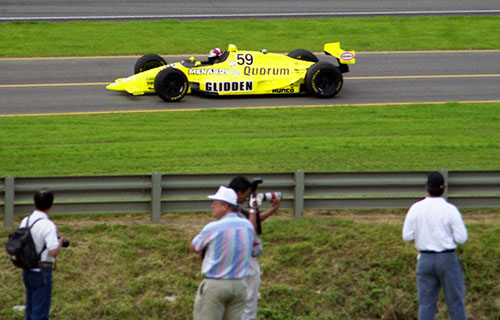

This is one of the first brand-new 'bespoke for Buick' Lolas, a T91/00. This year, the yellow-orange-and-red Glidden car used day-glo versions of their colours and its driver was new as well. Gary Bettenhausen drove this Menard entry and caused a major sensation when he became the fastest qualifier of the year. Regrettably for him, this happened on the second day of qualifying, so he did not earn pole position with his achievement. (photo HG)

Back in 1988, the latest design March Indycar, the 88C, had been sold in fairly decent numbers but its success was mediocre, no matter the engine used. A number of March customers switched to Lola cars during the season. Even second-hand '87 Lolas were popular since the '87 Lolas were still mighty competitive against the newer '88 generation of cars. In fact, Newman-Haas, the outfit closest to what could be regarded as a works Lola effort, provided a one-year-old T87/00 for Mario Andretti to drive at Indy!

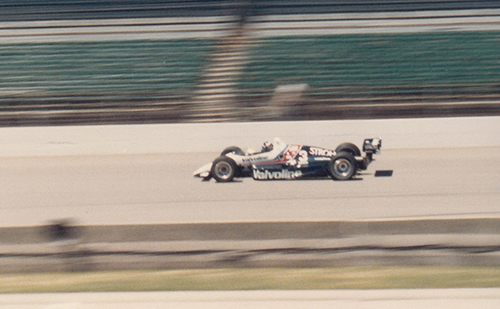

Indy 1988, the car fielded by Lola importer Carl Haas for his driver: a one-year-old Lola T87/00 with Chevy Indy V8 power. Andretti gave the T87/00 HU09 another chance of victory to make up for the heartbreak of the year before. (photo HG)

Galles Racing provided March 88Cs to their driver Al Unser Jr, who was the only driver managing to win races with the 88C that year, four to be precise. Apart from the Chevy-Indy V8 the team had access to, it may also have had something to do with the fact that Alan Mertens was on the workforce at Galles Racing. Mertens was one of the men behind the 88C's design before he left March ahead of the season. It is said that Mertens changed so much on Galles Racing's 88Cs that they had little in common with the basic March.

Some kind of proof that I saw a Galles Racing March 88C-Chevy for real. How much of this car was still March and not changed over to Galles-Mertens already? (photo HG)

March realized that the lack of success for their regular 87C and 88C against the equally generally available Lolas would cost them the market for customer cars, a market they once had all but for themselves. So they shelved their plans for a customer car but instead focused their efforts on two projects involving factory engines. During 1989, Porsche and Alfa Romeo each fielded a team using their own engine in bespoke Marches that were entirely different from each other, both projects that eventually proved to be the end of the road for March.

Galles could only join the Lola brigade in 89 but did fairly well that season, including being the loser in a spectacular two-car shootout during the last laps of the '500' that year.

May 28, 1989: Al Jr has crossed the finish line for the 198th time, followed by Fittipaldi on the verge of doing the same. This was the last time I saw Al race by again, little more than half a lap later... (photo HG)

At the end of 1989, Galles joined forces with Kraco Racing to create Galles-Kraco Racing, fielding Lola-Chevies for Unser Jr and Kraco driver Bobby Rahal.

Al Unser Jr had been the fastest man in practice (and up until that moment: ever) with an unofficial speed of 228.5 on May 11, 1990. Due to the weather his qualifying attempt could only take place on the second weekend of qualifying (5/19). Here, he returns to the pit lane from his much anticipated qualifying attempt, which yielded 'only' 220+ and 7th starting place. (photo HG)

The season ended with the CART title for Al Unser Jr, so it was quite a success. Although the team realized that by now they were one of many Lola users and they prefer to use their own car in order to gain an exclusive to them advantage, like Penske and Truesports Racing do. Besides that, the presence of Alan Mertens within the team is an ace in their sleeves. During the 1991 season, while fielding a Lola 9100-Chevy to defend the title, Mertens designs his own car that is eventually build in England.

Seen at the Milwaukee Mile in June 1991, proudly carrying the #1 again that it had to surrender to Luyendijk at Indy, a Galles-Kraco Racing T91/00-Chevy of defending CART champion Al Unser Jr. The X behind the 1 identifies this as a backup car. (photo HG)

Then, a lot of things happened at the end of the year: Kraco withdrew its sponsorship and Bobby Rahal left the team in order to drive for the revamped Pat Patrick Racing. Things happening in the entire CART Series also had its effect on things to come. Alfacorse withdrew its Alfa Romeo Indy V8 engines from the series but a new engine made its way into the 1992 CART starting fields: the ultra-compact Ford Cosworth XB.

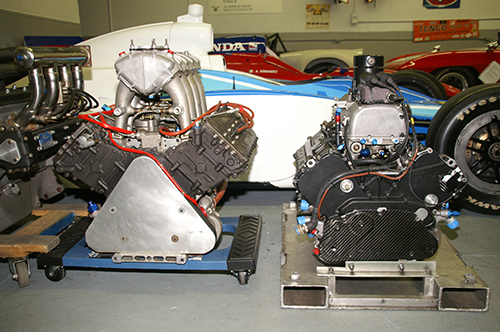

I admit that this isn't the best environment for taking pictures like this but sometimes you can't complain when you get the chance to see the real things next to each other. On the left is a Ford Cosworth DFX engine. On the right is a Ford Cosworth XB. The difference in frontal area and bulk for the actual engine blocks and potential this offered to the chassis designers is clear to see. (photo HG)

Newman-Haas Racing used the engines for Mario and Michael Andretti and Ganassi Racing had a deal for one engine for their driver Eddie Cheever. Both teams made use of a bespoke Lola chassis. It was derived from the regular T92/00 design but the XB-powered versions were lower and narrower behind the cockpit, in the fuel tank and engine bay area. In fact, so much lower that they made all other cars look bulky.

Meanwhile, Ilmor introduced a heavily reworked version of their own engine, inspired by the Ford XB. This new Ilmor V8 was eventually named Chevy/B after almost having been called a Buick. The lighter and more compact Chevy/B, however, remained exclusive to Team Penske. The older engine, known as Chevy Indy V8, was renamed to Chevy/A. This engine had been rather exclusive up until 1992 but more examples became available at last, not in the least least helped by the departure from the Ilmor camp by the Newman-Haas and Ganassi entries, and more teams were able to lease them. The only team turned down was Pat Patrick Racing! The reason was that Pat had sent two Ilmors to Alfa Romeo for inspection in late 1989 in order to improve the Alfa Romeo Indy V8. To little avail, but for Ilmor it was pay-back time when Patrick and Alfa separated, with Patrick inquiring about the availability of Ilmor engines for his team and Bobby Rahal. Pat could only salvage Bobby's 1992 season by selling his team to Rahal and his new partner Carl Hogan. When Rahal and Hogan approached Ilmor for engines they weren't turned down, with Patrick gone.

Since Galles Racing retained its deal with Ilmor their own car was powered by the Ilmor Chevy/A. The new car was called the Galmer (Galles & Mertens), the type number was G92. The arrival of the new Galmer chassis was a welcome addition to CART's 1992 starting fields and assured even more variety in the field.

Despite the loss of Kraco sponsorship, Galles still fielded two cars. Molson Beer was the new sponsor for the team that hired 1985 Indy winner Danny Sullivan for the second car. Ironically, Sullivan was the driver replaced by Bobby Rahal in the Pat Patrick team!

How the incorrect Indy record came into existence

The initial tests with the new Galmer were not that encouraging. But the team made a major breakthrough once they they employed a new front wing, inspired on the one used on the Leyton House F1 car. Galles Racing had some links with that outfit, and all of a sudden the G92 came good. Unser took pole in the opening race of the season in Australia but in the race finished fourth.

Both Unser and Sullivan were mighty competitive at Long Beach, with Sullivan ending up victorious, but only after a bitter duel between the two team mates. The loss cost Unser a streak of five successive victories at Long Beach.

The team had lesser expectations for Indy since they knew that their G92 was less suited to superspeedways. And if the opposition in CART was daunting enough already, at Indy it was even more impressive.

Buick had again invested big-time in their V6 program and ordered more bespoke versions of the latest Lola chassis. Apart from the regular T92/00 and the bespoke XB version, this was a third version based on the basic T92/00 design. Apart from King Motorsports (2) and Menard Racing (3), another such 'bespoke for the Buick' chassis was supplied to Dick Simon Racing, intended for Scott Brayton who would park the T92/00-Chevy/A he normally drove during the CART season. Besides that, Ganassi Racing fielded a second XB-powered Lola for Arie Luyendijk. So Arie also got his hands on a Lola specially built to accept the XB, identical to the cars of the Andrettis and Cheever.

Even though Menard had three T92/00-Buicks, just two of them were intended to be raced. Nevertheless, the CART regulars were confronted with at least six additional opponents driving cars that would be formidable opponents, especially during practice and qualifying.

During the practice period speeds yet unheard of were obtained. The 230mph barrier fell but only four were able to take this hurdle. King Motorsport team mates Roberto Guerrero and Jim Crawford represented the Buicks, Mario Andretti and Arie Luyendijk flew the flag for the 2.65-litre quadcam brigade. The smaller frontal area and the better streamlining of the XB-Lolas made them the only quadcams capable of making up for the power advantage the Buicks had on the majority of the field.

Due to Pole Day being rained out for most of the day, all runs eligible for the pole were held on both Saturday and Sunday. Because of this, and engine failure at the wrong moments, poor Jim Crawford lost his chance of winning the pole. Menard Racing had lost one of their T92/00-Buicks when Nelson Piquet had a violent crash in it. Other than that, the remaining six bespoke Lolas, either Buick or XB-powered, fulfill the expectations. Guerrero (and Buick) claimed the pole, ahead of the XB-Lolas of Cheever, Mario Andretti and Luyendijk, Gary Bettenhausen is 5th fastest in the remaining primary Menard T92/00-Buick and Michael Andretti is 6th.

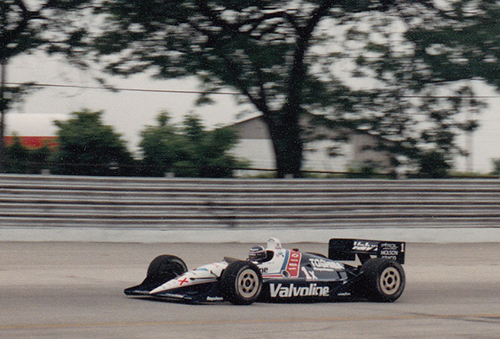

Some kind of 'Cheever's corner' in this article. I was not at Indy in 1992 so I can't show any self-made pictures of a 1992 car in its 1992 colours. However, some of the cars on the first two rows of the 1992 starting field made it back to the Speedway one year later. Based on the info I had available about the chassis numbers, the yellow #59, here seen driven by Eddie Cheever in 1993 was the T92/00-Buick #51 of Gary Bettenhausen in 1992. The #84 driven by John Andretti was a Foyt entry in 1993 but one year before it had been the #9 Target car raced by: Eddie Cheever! As can be seen, the fuel tank and engine cover on the #84 are lower than on the #59, a major asset for the T92/00-XBs on all their opponents in 1992. (photos HG)

Scott Brayton was less spectacular during practice than the other (King and Menard-entered) T92/00-Buick drivers but in qualifying he gained 7th place. Jim Crawford, the second King Motorsports driver, eventually qualified his car in 21th place, but as sixth fastest in the field. In other words: the eight 'bespoke' Lolas that qualify (out of nine such cars that practised) are the eight fastest cars in the starting field.

The Chevy drivers had nothing to offer against the bespoke Lolas, no matter the chassis in which the Chevies were used. One year before the limited availability of these very same engines caused controversy and hard feelings, this year at least in practice they were mere also-rans. Even Penske, ever so strong between 1988 and 1991 in practice and qualifying, was left without prizes, the exclusive Chevy/B offering little benefits. Rick Mears and Emerson Fittipaldi are among the five fastest Chevies overall but that's about it. The first Chevy in the starting line-up was, surprise, surprise: Danny Sullivan in his Galmer who managed to qualify in 8th (9th fastest) position. Teammate Al Unser Jr was 12th on the grid but once the field was settled he was 'only' 14th fastest in the field. After qualifying Junior stated that on Race Day it would be a matter of trying to stay on the lead lap and then the 'Fords' and the 'Buicks' needed to break down.

If the Chevy/A was reduced to an 'also-ran' in qualifying and practice, 1992 spelled not only the end of the Judd V8 engines at Indy but it was also the end of the road for the Cosworth DFX/DFS varieties, once the almighty powerhouse at Indy. There had been years with more than 30 Cossies in the starting field, but not a single DFX/DFS-powered car made it into the 1992 race. The only representatives for Ford were the 4 XB-powered cars of Newman-Haas and Ganassi.

Among the practice also-rans was Walker Racing, fielding a regular Lola T92/00-Chevy/A for primary driver Scott Goodyear and a ’91 Lola-Chevy/A for Mike Groff. The team ended up in a big qualifying mess due to the weather and also had a most unfortunate draw in the qualifying line-up. The team decided on swapping the drivers during qualifying and back to their assigned drives for the race. The plan failed miserably when Goodyear ruined his qualifying attempt and as a result was the last driver to be bumped from the field. Since he was Walker Racing's season-long driver he still took over the car qualified by Groff and would start the race in 33rd place.

Another driver qualifying for the race was Al Unser Sr who was hired to drive the third and last '92 Menard-entered Lola-Buick, the backup car that was pressed into service to replace the car wrecked by Piquet in practice. He was 22nd on the grid but 12th fastest. Apart from the extreme speeds, practice was marred by a number of accidents with a seriously injured Nelson Piquet and the fatally injured Jovy Marcello being the low points.

Once practice and qualifying was done, everyone knew that the race itself would be an entirely different game. Those bespoke '92 Lolas might be the fastest cars in the field but that was because of their engines, be it Buick or XB. Yet these very same engines provided the big question mark hanging above the race results for all bespoke T92/00s. Race day reliability for the Buicks had been appalling in the past. Not a single Buick-powered car had yet completed the full 200-laps race distance. The five '92 Buicks entered the race in a cloud of uncertainty about their durability. Although for different reasons, the same applied to the 4 XB-powered cars. This would be the first 500-miles race for the XB: reliability over such a long distance was still up in the air. Besides that, half of the XB-Lolas were driven by a driver whose family name was Andretti, a name that appeared to be jinxed since 1969. That almost eliminated these two Lola-XBs by default. Altogether, many insiders and railbirds proclaimed that due to proven reliability the odds for the race shifted back to the Chevy/A brigade, primarily the '92 Lola-Chevy/A drivers, and of course you could never count out the Penske entries.

Glancing over the '92 starting field, it seemed pretty dull if you only looked for the chassis brands: one Truesports, two Galmers and three Penskes against 27 Lolas. But breaking this all up into different types of chassis and engines, the field appeared more varied. Those 27 Lolas could be split up in seven different varieties, so here a complete rundown of all chassis-engine combos represented:

- 1 x '92 Truesports-Chevy/A

- 2 x '92 Galmer-Chevy/A

- 2 x '92 Penske-Chevy/B

- 1 x '91 Penske-Chevy/A

- 1 x '90 Lola-Chevy/A

- 1 x '90 Lola-Buick

- 5 x '91 Lola-Chevy/A

- 5 x '91 Lola-Buick

- 4 x '92 Lola-Ford Cosworth XB

- 5 x '92 Lola-Buick

- 6 x '92 Lola-Chevy/A

No-one could have predicted how bizarre the race would eventually be. Like qualifying being affected by the weather, so was the race. Never before in history the temperatures on Race Day had been that low. The cold prevented the tyres from warming up properly and the cars ran with a lack of grip. A major shock took place during the warm-up laps when pole sitter Guerrero waved on the back stretch of the track to heat up his tyres but lost control and spun helplessly out of control into the infield, damaging his car beyond repair against a retaining wall. Out of the race even before it actually started! It was the first of many accidents caused by cars losing grip and crashing out.

The race was a chore for the crowd due to the cold and the many laps spent behind the pace car as a result of all those accidents. Several of these took place literally seconds after the race had gone green again because of drivers spinning off due to their tyres being too cold.

Lynn St James, who qualified a '92 Lola-Chevy in the race and finished 11th, which earned her the Rookie of the Year award, had the following explanation as to why many of her more experienced colleagues spun out. Most of her racing experience had been with closed prototypes and GT-style cars which, at the moment of a restart, rarely had their tyres at the right temperature. For that reason, she was used to taking things easy after the restart, instead of going for it instantly. Indycar drivers, on the other hand, were far more familiar to tyres close to optimal temperatures at the moment of a restart when warmed up properly, so by instinct these men would go flat out right after the restart. On that particular day, it was simply too cold for that to happen, and many experienced drivers found themselves on tyres that were too cold, spinning off as a result. Lynn felt that they simply were too impatient for the exceptional circumstances of that day, while her own experiences with restarts were of great value for keeping the car going. As a result she gained a creditable finish which gave her the prestigious Rookie award.

And once the race was under green it was still boring since no-one was able to live with Michael Andretti. He was by far the fastest driver out on the track and appeared unstoppable. 'The Andretti curse' had more work to do in a year with no less than four Andrettis in the field, but with so many potential victims, the curse simply had a field day.

Michael's brother Jeff had a tremendous crash and gravely injured his legs. Father Mario also crashed and ended up with injured feet, yet nowhere near as serious as Jeff. After all of this, a victory for Michael would be bitter sweet, yet still sweet. But the Curse had no mercy. With 11 laps to go and at least a lap on the entire field, Michael's day sadly came to an end. The fuel pump had broken down, a result of aggressively revving the engine during the yellows to keep the heat in the tyres. Once the crowd realized that the man who had the race in the bag is out, they were in for the next shock: the lead was handed to Al Unser Jr, but right behind him was Scott Goodyear. The duel for second place would become a shootout for victory!

The restart was given on the 193th lap but whatever he tried Goodyear was unable to make a move on Unser who once again proved his skills as a defensive driver. Tom Sneva had a similar experience nine years before although that wasn't for track position. When Unser and Goodyear headed to the finish flag, Goodyear made his final and desperate attempt to overtake Unser but he couldn't pull it off. The difference in time was listed as 0.043 seconds, the closest finish ever, even closer than the thriller between Gordon Johncock and Rick Mears ten years earlier. Again, despite outnumbering the field handsomely, Lola was unable to make it to Victory Lane yet again.

The Galles team appeared to have every reason to celebrate: out of the four races run they had won two of them, including 'the big one'. No matter what followed that season, tragedies excluded, the Galmer G92 would always be rated as a success. But later on, it transpired that on the morning of the race, just a few hours before the Galmer wrote history, the team had decided not to continue the project beyond 1992. They would go back to Lolas the next season. Tellingly, the remainder of the season was nowhere near as good as the first four races. Al Unser Jr scored a few more podiums but failed to add more victories. In the final stages of the season he was still within a shot of the title but in the last two races the Galmer came short. Unser still finished third in the standings behind champion Bobby Rahal and Michael Andretti. Sullivan had a lesser season but still ended up seventh.

After the end of the season Galles sold off the cars, the Indy-winning chassis was bought by the Valvoline Company and brought back into the victorious Speedway trim. Even if it was effectively a one-year-only effort, the Galmer G92 still made quite an impact at the Speedway and holds an enviable record. It's also memorable for the record books still listing that 0.043 seconds as Indy's closest finish ever.

May 2008 saw some celebrations for the Unser family efforts at the Speedway. Every family member who had been victorious at the track (a few of them didn't win) had one of his winning cars out on the grounds early on in the month. For Al Jr, the choice (likely related with availability...) had fallen on the 1992-winning Galmer. (photo HG)

It was little over a month later when an American newspaper printed a tiny bit of information about the winning margin. It certainly wasn't given any major headlines and so this detail was missed and all but forgotten for a long time. Many years later, it eventually found its way onto the Internet, so by now it is not that much of a secret anymore. However, for a certain period of time since May 1993, when I found out about it, it appeared to me that I was among the very few who knew about it. And we also understood why. It was something that IMS and USAC didn't want the large audience to know since they had escaped major embarrassment with only 1/30th of a second to spare...

The secret behind the erroneous record becomes known among a limited group of people

It is May 1993. I am at the Speedway for most of the Month of May. I have a heck of a Pole Day, seeing my fellow countryman Arie Luyendijk win the pole on what also must be the day on which four-time winner Rick Mears will be honoured after his retirement from racing. But another four-time winner spoils the party for Rick when after some initial practice laps he all of a sudden decides to quit racing at last. Everything else that day is insignificant compared with AJ's sudden retirement. The festivities organized for Rick Mears appear redundant, untimely. Arie's pole or any other notable qualifying effort and event of that day, all of it has been made instantly irrelevant.

I have noticed that many autograph hunters are on the prowl for the autographs of both Al Unser Jr and Scott Goodyear on prints of pictures taken of their stunning finish last year. I don't think it will bother Al that much but it must be tougher on Scott to see the proof of his defeat ever so often again.

Then, on Monday, May 17th, walking through Gasoline Alley, I spot a car that much to my surprise appears to be a Galmer and on close inspection indeed turns out to be one!

A surprising discovery for me on May 17th, 1993, in Gasoline Alley, the start of even more surprising events. That left sidepod we look at had quite a story to tell... (photo HG)

Detail shot of the Galmer's aero. (photo HG)

I follow the car when it is pushed to its garage to find out where it belongs. After some talking, a mechanic allows me to inspect the chassis plate of the car so I dive into the garage for a quick pic.

The definitive identification of the Galmer that was at the track in '93. (photo HG)

Then I hear my name called from further inside the garage. I look up and see a young man coming up to me. I recognize him. Yesterday, I met him and his friend in the Museum where we chatted about some of the cars exhibited there. I ask what he does for the team and who will drive the Galmer. Dominic Dobson is supposed to drive the car but when I ask if that will happen this afternoon, he chuckles. He says it is their intention once they have solved the problem they worked on this afternoon. With something of a smile he goes on to tell that the team was hugely surprised by their mishap, which caused them to do a lot of improvising. When asked he tells that the time-keeping transponder didn't fit in the sidepod where it should be stored. It turned out to have been a problem last year as well but this time the USAC officials insisted that the transponder had to be located in the specified place. The smile he shows while telling all this makes me wonder if there is something going on here.

We continue our discussion, and so I learn that the transponders are unchanged from last year. I wonder why the transponder didn't fit last year and what was done to solve the problem. So then I hear a little known big secret, a secret that could have caused utter embarrassment for the Speedway and USAC.

My friend tells me that when the team discovered that they were unable to squeeze the transponder in its allocated position they had a talk with one of the officials. The official informed them that it had been a problem last year as well but that it was solved by putting the transponder in the nose, where there was enough room. But because of the way last year's race evolved, USAC's officials wouldn't allow that anymore and insisted the sidepod had to be modified to make room for the transponder.

From that point, the discussion between the two of us went on something like this:

"Because of last year's race?" I asked, not understanding instantly what this could be all about. With a smile on his face my friend replies: "Remember the finish last year?" Two seconds later it dawns on me. "Wait a minute, if Al had his transponder in the nose and Goodyear carried his in the sidepod, Al would have been declared the official winner by Timing & Scoring as long as his transponder was ahead of Goodyear's one even if he was behind Scott!"

"Yep! Can you imagine what that could have caused? And do you understand by now why USAC want that transponder in the sidepod this year?"

"You bet! Had Goodyear passed Unser with only a nose wing length, then Al's transponder would still have crossed the finish line first and Timing & Scoring would have declared him the winner instead of Scott", I answer in sheer amazement.

"That was what we came up with too. Oh man, we had something to talk about when those USAC officials had told us what to do and why."

The discussion continued. My friend told me how the crew realized this was the first time they heard anything about that, and that it had been kept a secret. And it probably would have remained a secret had it not been for the fact that they entered a Galmer for the '93 race, so USAC had to take action. We then concluded that the official time difference of 0.043 was in fact too large and would have been smaller if the cars had carried their transponders in identical places. Which, of course, if confirmed should have created even more excitement about the outcome of the race and made the record even more impressive. But it still stood at 0.043 seconds. Eventually we concluded that IMS and USAC didn't want this to be known since it could have been too embarrassing. So much at the Speedway was under tight control and well organized. But in this case, with a transponder not fitting properly, the organization had opted for the easy way out and a quick compromise, not even thinking about the possibility of one of the cars being involved in a photo finish. They got away with it but barely. However, if Scott Goodyear had managed to overtake Unser in those final yards with less than the distance between the two transponders it would have been a very awkward situation. Seen from the perspective of IMS and USAC, it certainly made sense to keep this fact a secret.

By now we understood why the USAC officials had been so fierce in enforcing the transponder to be located in the Galmer's sidepod, even if it required the Burns crew to do a lot of work.

Ever since that day I knew I was among the few to know about this little known detail in Indy history. Given what had happened that afternoon in the Burns Racing garage and the way it was told to me, despite the fact that I had never read anything about it anywhere for a long time, I never doubted the story.

It was in fact many, many years later, around 2011, that I finally found a clue to this story on the Internet, the proof that even within IMS the story had been confirmed as early as July 3rd, 1992 and had been printed in that day's New York Times. Using all kinds of speed data it had been calculated that the actual time difference between the two cars should have been 0.0331 seconds instead of 0.043, even though the 0.043 would remain official. And it still is. And for good reasons as far as I can figure out. Somehow the story about the transponders has still gone almost unnoticed. You may wonder what would have happened if the story in the NY Times had been picked up by media outlets more significant to motor racing.

Nevertheless, 0.043 is no longer the smallest time difference between the first two cars at the finish of an event at the Speedway. Even if it would be corrected to 0.0331, it will still only be the closest-ever finish for the '500' but no longer for any IMS event. Take a look at the last lap of the 2013 Firestone Indy Lights for that...

When in 2011 the IMS museum gathered the largest collection of Indy-winning cars together for display to celebrate the 100th anniversary, the winning Galmer was present as well and a welcome interloper in that section of the exposition, dominated by the many white-and-dayglo-red coloured Penske chassis. (photo HG)

Bibliography

- Carl Hungness, Indianapolis 500 Yearbook 1992, Carl Hungness Publishing, Speedway IN, USA. ISBN 0-915088-58-4

- Carl Hungness, Indianapolis 500 Yearbook 1993, Carl Hungness Publishing, Speedway IN, USA. ISBN 0-915088-61-4

- Ian Wagstaf, The British at Indianapolis, Veloce Publishing Ltd, Dorchester UK, ISBN-10: 1845842464, ISBN-13: 978-1845842468

- New York Times, ed. 3 July 1992, article SPORTS PEOPLE: AUTO RACING, SPORTS PEOPLE: AUTO RACING, Indy 500's Finish Was Even Closer

- Wikipedia page 'Galmer'