Rear View Mirror

Volume 8, No.2

Author

- Don Capps

Date

- August 2, 2010

Download

- RVM Vol 8, No 2 (PDF format, 1.5MB)

“Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson | Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman

Brooklands: 1907

1

Although I was aware of the early idea to incorporate the using of “racing silks” as used in horse racing into the Brooklands “scene,” up to this point I had not seen a listing for more than a few of the drivers concerned. It was, therefore, something that certainly caught my eye when I stumbled across this listing of the proposed “racing colours” to be used by the drivers when competing at the track. Although short-lived, this idea was an interesting one, even if somewhat impractical, even for the time.

Racing Colours for Brooklands Racing Track2

| Name. | Colours. |

| Bircham, F. R. S. | Green coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Baxter, Paget | Yellow coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Brabazon, J. T. M. | Chocolate coat, Blue sleeves and cap. |

| Bell, J. H. | Black coat and sleeves and White cap. |

| Baxendale, G. V.... | Royal Blue coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Browne, S. Gore-... | Black coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Coleman, F. | Red and Black striped coat and cap. |

| Edge, S. F. | White coat and sleeves and Green cap. |

| Fry, F. R. | White and Pea-green halved coat and sleeves, Pea-green cap. |

| Hutton, J. E. | Blue coal and sleeves and Primrose cap. |

| Hutton, J.E., 2nd col. | Primrose coat, sleeves, and Blue cap. |

| Howell, G. Ll. H. | French-Grey, Primrose facings, French, Grey cap. |

| Instone, E. M. C. | White coat, Red, White and Blue sleeves, White cap. |

| Jarrott, C. | White coat, sleeves and cap. |

| King, A. F. | Dark-green coat and cap, Gold sleeves. |

| Keating, H. S. | Red coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Levitt, Miss Dorothy | White coat and sleeves, Blue cuffs and cap. |

| Moss, Geoffrey | White coal, Mauve sleeves and cap. |

| Okura, K.... | White coat and sleeves, and Pink cap. |

| Pope, H. R. | Red, White and Green stripes. |

| Sangster, C. | Fawn coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Thornycroft, T. | Crimson Lake coat and sleeves, White collar, cuffs and cap. |

| Wright, Warwick J. | Skyblue coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Walker, A. Huntley | Cambridge Blue coat and sleeves, Black collar, cull's and cap. |

| Wigam, C. Harman | Heliotrope coat, sleeves and cap. |

| Martin, Percy | Red coat, Red, White and Blue sleeves, White cap. |

| Barwick, George S. | Blue coat, Red, White and Blue sleeves, White cap. |

| Smiley, P. Kerr- | White coat, sleeves and cap, Eton Blue cuffs and collar. |

| Owen, Capt. W.E.D. | Yellow and White halved coats, sleeves and cap. |

The Rules of the Game / La Règle du jeu – I

Here is an English translation of the regulations for the Paris to Bordeaux event which was run on 11 June 1895.3 This was presented as a “historical document,” although scarcely a dozen years had passed from the time of the event regulations appearing to their being republished.

Regulations of the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris Motor Car Race, June 11th, 1895.

The Executive Committee in charge of the arrangements: - M. Marcel Deprez, of the Institute, and M. Georges Berger, deputy of Paris, presidents.

M.M. Baron de Zuylen de Nyvelt, Gordon-Bennett (New York Herald), Comte de Dion, A. Peugeot, Levassor, P. Giffard (Petit Journal) , Capitaine de Place, Serpollet, Marquis de Chasseloup-Lauhat, Recopé (chief engineer of the Navy), H. Menier, H. de la Valette (Génie civil), P. Meyan (Figaro), Max de Nansouty (Temps), Fernand Xau (Journal), Marc (Illustration), Pierron (vice president of the Touring Club de France), Hervé-Lefranc (Velo, official organ of the committee), Emile Gautier (Science Française, weekly official organ of the committee), Raoul Vuillemot (Locomotion Automobile, monthly official organ of the committee), Broca, Michelin, Korda, Avril, Dumont, Quentin-Bauchart (conseiller municipal de Paris), Mauclére, Pérignon, Maurice Martin (Veloce Sport), Leon Francq, Pilot, H. Deutsch, Weidknecht, J.-J. Heilmann.

The general managers of the Exhibition, M.M. Thévin and Houry. Secretary, M. Yves Guédon.

Rules.

1. The race is international. Only manufacturers or inventors will be allowed to take part.

2. The course will be from Paris to Bordeaux and back without stop (about 1,200 kiloms.). Vehicles carrying at least two passengers will alone be allowed to take part; the only exception to this rule being bicycles, tricycles, and quads as mentioned in Rule 13.

3. Only vehicles propelled by mechanisms deriving their force from other than animal power will be allowed to take part.

4. The subscriptions received amount to 68,000 francs, which, together with the money obtained from entrance fees, exhibitions, &c., will, after the deduction of 5,000 francs, as mentioned in Rule 13, and the payment of the expenses of organisation, be divided as follows:-

First to arrive at Paris, 50 per cent.

Second to arrive at Paris, 20 per cent.

Third to arrive at Paris, 10 per cent.

The next four, 5 per cent.

5. The first prize will only be awarded to a vehicle carrying four or more passengers.

6. An Exhibition will be organised to extend over 15 days, commencing Friday, June 6th. Exhibition of the vehicles will be obligatory on the competitors during June 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th, but optional after the race. The Exhibition will be held in the Rapp Gallery (Champ de Mars).

7. The start will take place on June 11th from the Place de la Concorde. The return will be made via Porte Maillot, the arrival control being at the Gillet Restaurant.

8. Vehicles entered before May 1st, 1895, pay an entrance fee of 200 francs.

9. Vehicles entered after May 1st pay a double entry fee (400 francs).

10. The number of vehicles entered by any manufacturer or inventor is unlimited, but competitors may not enter several vehicles of the same type and dimensions.

11. Competitors may change drivers during the race.

12. Vehicles must carry the number of passengers for which there are seats, or equivalent dead weight at the rate of 75 kilogs. per passenger absent.

13. A sum of 5,000 francs will be set aside from the money at the disposal of the Executive for the purpose of awarding a special prize to mechanically-propelled quads, tricycles, and bicycles carrying one passenger, and not exceeding 150 kilogs. in running order but without the rider.

14. This 5,000 francs will be divided as follows:

2,500 francs for the first who arrives in Paris.

1,500 francs to the second who arrives in Paris.

500 francs to the next two who arrive in Paris.

None of these special prizes will be awarded unless the vehicles cover the course in a maximum time of 100 hours.

15. Repairs en route of any nature whatsoever may only be carried out by the proprietor of the vehicle or his representative, with the material and outfit carried by each vehicle, and under the control of the observer.

Something Worthy of Note.... I

4

The Rules of the Game / La Règle du jeu – II

Here is an article originally published in the “Races, Records, and Trials” section of The Automotor Journal announcing the Tourist Trophy race for 1905.5 Given that the “Tourist Trophy” was once considered Britain’s premier motor sports event, being given a place on the international sporting calendar alongside events such as the Grand Prix l’Automobile Club de France and the International 500 Mile Sweepstakes Race, that is seems to have faded into obscurity is, perhaps, simply another sign that when it comes down to the nitty-gritty, automobile racing is indeed a cruel sport in many aspects, history and the past inevitably giving way to the concerns and needs – real or imagined – of the present.

THE “TOURIST TROPHY."

UNDER the above title, the rules are issued by the A.C.G.B.I. of the proposed big race for tourist types of cars, which was originally put forward under the title of the United Kingdom Cup. It will be remembered that the idea of this important contest is to promote improvements in the ordinary everyday car in use, rather than to offer further premiums, on the lines of the Gordon-Bennett Cup Race, for the further development of the racing car pure and simple. A special Commission was appointed by the Automobile Club last October, consisting of Mr. Claude Johnson (Club Committee), Mr. J. D. Siddeley (Industrial Committee), Major F. L. Lloyd, R.E. (Technical Committee), and Mr. E. H. Cozens-Hardy (Races Committee), who, with the club secretary, were deputed to draw up the rules for this cup. The chief points governing the trophy laid down by the A.C.G.B.I. committees were: (1) That the quickest time accomplished should determine the winner; (2) That a limited volume of fuel should be allowed for a certain number of miles;(3) This amount of fuel to be such as to permit an average speed not exceeding 25 m.p.h.; (4) That the weight of the chassis should be between 1,323 lbs. (600 kilogs.) and 1,660 lbs. (750 kilogs.); (5) That the chassis should carry a dead weight of not less than 10 cwt., including body and four passengers, but exclusive of tools, water, fuel, &c.; (6) That the wheel track be not less than 4 ft., and the wheel base 6 ft. 8 ins.

In the following regulations, now issued by the club, the weight of the chassis is, however, to be from 1,300 lbs. To 1,600 lbs., the dead weight carried by the chassis has been reduced to 950 lbs., calculated to give a minimum total weight of 21 cwt., and the wheel base has been lengthened to 7 ft. 6 ins.

It is recommended that if practicable the first race should be held in the Isle of Man during the month of September, 1905.

The Regulations.

General.-1. The Tourist Trophy shall be put up for competition between May 1st and October 1st in each year on a date to be fixed by the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland (hereinafter called “The Club”), and to be advertised in the Automobile Club Journal not later than the preceding 1st of March. The competition shall take the form of a race for touring cars, irrespective of make or of country of origin, with a limited quantity of fuel under the following conditions:-

2. The race shall be held under the Competition Rules for the time being of the club in the United Kingdom or such other place as may be appointed by the Club, and shall be organised by the Club or by their nominees.

3. Cars may be entered by members of any recognised foreign automobile club and of any automobile club or organisation in the United Kingdom which is affiliated to the Club.

4. The distance of the race, including controls, shall be not less than 150 and not more than 250 miles.

5. The fuel to be used shall be provided by the Club, and shall be petroleum spirit, having a specific gravity of 0.695 to 0.705 at 60 deg. Fahr. The allowance of petroleum spirit shall be determined by the Club, according to the nature of the course selected and the conditions of road surface on the day of the race.

The allowance for the course selected shall be equivalent to an allowance of one gallon of petroleum spirit for every 25 miles of dry average road – the term "average road" signifying a course similar to the road from London to Oxford, viá Uxbridge, High Wycombe and Stokenchurch.

6. The car completing the course in the shortest time shall be the winner, subject to compliance with these regulations, and the entrant of the car shall, on signing the bond and effecting the insurance required by the Club, become holder of the trophy.

7. In case the trophy shall not be advertised for competition at the proper time, the holder shall be entitled to give one calendar month's notice to the Club of his intention to drive over the distance for it, and, in default of competition, he may do so on a course appointed by the Club. Such a drive over shall count as a win to the said holder.

On receiving such notice from the holder the Club shall be at liberty to advertise the trophy for competition, and accept entries for it as if the advertisement had been duly given, and to have it competed for at the expiration of the notice. The Club may at its discretion allow the trophy to be held over for such period as it thinks fit, and in such case the trophy shall remain in the custody of the holder until the next race.

8. No vehicle shall be driven in the race unless it conforms with the requirements herein contained.

9. The weight of the chassis shall be not less than 1,300 lbs., nor more than 1,600 lbs. Accumulators and other ignition apparatus, the tyres on the wheels, the bonnet, tanks (empty), dashboard, steps, lamp brackets, and front mudguards, shall be treated as part of the chassis.

No ignition accumulators or magneto or other source of electric energy shall be carried except those fixed to the chassis at the time of weighing.

10. The load carried by the chassis, exclusive of fuel, oil and water, spare tyres, spare parts, luggage and provisions, shall be not less than 950 lbs., including:-

(1) The body with rear mudguards and their stays, floor boards, and lamps.

(2) The driver and one passenger, averaging not less than 11 stone each; and

(3) Not less than 300 lbs. of loose ballast in the portion of the body in which the two unoccupied seats are situated.

11. The chassis shall have not less than four road wheels. The distance between the centres of the wheels on each axle (i.e., the track) shall not be less than 4 ft., and the distance between the centres of axles (i.e., the wheel base) shall not be less than 7 ft. 6 ins. Efficient mudguards to the front wheels shall be fitted to the chassis.

12. The body shall be of the ordinary touring type, properly upholstered, comfortably seated for driver and three passengers facing forwards, two in front side by side and two behind side by side, on seats at least 34 ins. from the ground, and giving for every two seats a clear seating space not less than 40 ins. wide between cushions. Efficient mudguards to rear wheels shall be fitted to the body. The platform behind the dash board shall not be less than 6 ft. 6 ins. long, nor less than 30 ins. wide.

The body of the car shall be easily removable, to facilitate the slinging of the body for weighing.

13. Drawings to scale of the body to be used in the race shall be submitted before March 1st, and the Club may refuse to admit a body which in their opinion does not afford sufficient comfort or protection for touring purposes.

14. Between the start and finish of the race the driver and his passenger shall alone be permitted in any way to assist a car, and no stores, supplies, spare parts or spare tyres other than those actually on the car at the start shall be taken on to the car during the race. Everything (except fuel) which is on the car at the start must be carried throughout the race.

Entries.-15. Entries for 1905 will be received by the Club, at 119, Piccadilly, London, W., at any time after the publication of these regulations, and for subsequent years after the last race. The holder of the trophy shall, unless be give written notice resigning the trophy, or unless he be not qualified for entering a car, be considered as having entered a car without a fee for the next race.

16. Not more than two cars by one manufacturer will be accepted. The Club reserves the right to refuse any entry, and to limit the number of acceptances as circumstances may require. Subject to these provisos, entries which comply with these regulations will be accepted in order of receipt, provided always that the first entry of a manufacturer shall have priority over the entry of one of his cars by a private owner or by an agent.

17. The minimum entrance fee shall be £20 per car. For each week after the expiration of three months from the first day for receipt of entries the entry fee shall he increased by £1 per week.

18. The entry fee will be returned in full if no race is held in the year. When the entry has been accepted the entry fee will not otherwise be returnable.

19. Every entry shall state the maker's selling price of the chassis, and shall be accompanied by a written guarantee by the manufacturer of the car to accept at the declared price all orders within one month after the race for exact duplicates of the chassis entered and to deliver all such chassis so ordered complete and in perfect working order within a reasonable period from date of order, provided a cash deposit not exceeding one-third of the price of the chassis is paid at the time of giving the order. Should the manufacturer fail to comply with such guarantee, the name of such manufacturer may be struck off or kept off the competitors' register at the discretion of the Club for such period as it thinks fit.

Fuel Tanks. -20. Every car shall be provided with fuel tanks capable of holding not less than twelve gallons

21. No vents to atmosphere from tanks or from pipes connected therewith shall be more than 1/32 of an inch in diameter.

22. There shall he provided on each car one or more cocks or unions in such positions that when opened all fuel whatsoever on the car, whether in the tanks, in the carburettor, in the pipes, or elsewhere, shall be drained off dry through such cocks or unions in not more than five minutes.

23. Such means as the Club may require for sealing the tanks shall be provided by the competitor.

Weighing and Examination.-24. The Club shall appoint a place for weighing and a day and hour prior to the race on which cars must be presented for weighing. Cars shall be towed with tanks empty to the weighing station, but shall be driven away under their own power.

25. All ballast required in these regulations shall consist of canvas bags of sand, weighing 50 lbs. each, and shall be provided by the competitor.

26. Every car which finishes the course shall thereupon be driven to the Club enclosure under supervision, with its passengers and full load, to be re-weighed, and fuel tanks, water tanks and lubricant reservoirs shall be emptied by the Club. If after the race the weight of chassis and weight of load carried respectively are found not to conform to the regulations the car shall be disqualified. The Club shall fix an hour after which no car will he received for re-weighing.

27. The Club reserves the right to take such steps as it may deem necessary to examine the tanks and fuel system of any car on conclusion of the race.

Road Regulalions.-28. The driver need not be a member of an automobile club, but must be on the Competitors' Register of the Club.

29. The driver and one passenger shall be the only persons on the car during the race.

30. No vehicle shall be pushed or pulled over any part of the course under pain of disqualification.

31. No fuel capable of being used for propulsion of the car in question shall be carried on the car, except the fuel provided by the Club.

General Regulalions.-32. A competitor by entering or by driving thereby agrees that he is bound by the competition rules of the Club anti by the supplementary regulations herein contained.

33. The interpretation of the regulations contained herein shall be entirely with the Club, which may at its discretion waive, alter, add to, or omit from, any or all of them from time to time. If any dispute shall arise in connection with these regulations, or h the race, the decision of the Club shall be final and binding, except in so far as is otherwise provided under the competition rules the Club.

34. The Club reserves the right to abandon the race if it does not consider the number of entries sufficient, and to postpone the race if circumstances arise which, in its opinion, render such course desirable.

35. The entrant shall be responsible for all acts or omissions of driver.

36. It is one of the conditions upon which entries are accepted by Club that the Cub shall not be responsible for any damage that by be done to .the vehicle entered, or to its appurtenances, either during the race or while the vehicle is under the charge of the Club, either by fire, accident, or otherwise, nor for the theft of the vehicle, my of its accessories or appurtenances. The vehicles, and their accessories and appurtenances, shall at all times be at the risk in all aspects of the entrant, who shall be deemed by entering to indemnify, the Club against all civil and criminal proceedings, costs, and penalties whatsoever relating to or arising out of the race.

37. If a competitor fails to comply with these regulations his vehicle shall be liable to disqualification.

38. A competitor by entering or by driving waives any right of action against the Club for alleged damages sustained by him in sequence of any act or omission on the part of the Club or of its servants or representatives with respect to these regulations; or to any matters arising therefrom.

The Rules of the Game / La Règle du jeu – III

Here is a contemporary report from The Automotor Journal on the Ostend Agreement. In American racing history the Ostend Agreement perhaps figures more prominently than it does in the history of European automobile racing. The agreement came to be an element in the many issues that the Automobile Club of America (A.C.A.) and the American Automobile Association (A.A.A.) squabbled over during 1908. Although there are those who have suggested that this was the catalyst and root of the disagreement between the two organizations, I would suggest that it was just one of many issues that the two disagreed about, this aspect not being mentioned until after the A.C.A. had already publicly announced its intention to withdraw – secede being the term used at the time and which best reflects what actually took place – from the A.A.A. in March 1908. This is, however, a story for another time.

International Rating for Racing Cars.6

THE most important subject which was before the International Conference of Motor Clubs on Monday last at Ostend, was to consider whether it were possible to arrive at a universal rating for racing cars.

Count Jacques de Liedekerke, of the Belgian Club, presided, and there were present delegates from France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Austria, Holland, Spain and Hungary, as well as from England. The English representatives were Mr. J. W. Orde, Secretary of the R.A.C., and Mr. Mervyn O'Gorman. At an early stage in the proceedings it was decided in principle that a maximum bore and a minimum weight would constitute the best means of classification. The English proposal was for a bore of 152 mm. (nearly 6 in.) and for a total running weight of 1,300 kilogs. (2,866 lbs.), whereas the French suggestion was for 160 mm. (nearly 6 5/16 in.) bore, with a tare weight of 1,100 kilogs. (2,425 lbs.), and Germany brought forward the suggestion of 135 mm. (5 5/16 in. full) bore, with a tare weight of 1,175 kilogs. (2,590 lbs.). Ultimately after some discussion it was agreed between them – and the decision was accepted by the representatives of all the other countries – that the standard classification should be 155 mm. (6 3/16 in. full) maximum bore, with a minimum weight of 1,100 kilogs. (2,425 lbs.) for the chassis with its complete body (except wings), and including lubricating oil and fuel. The abovementioned bore is, of course, for 4-cylinder engines only, but the Congress agreed that a technical commission should be charged with the duty of fixing equivalent figures for 6-cylinder and for 8-cylinder engines, or for engines working on any other system.

One or two other questions were raised concerning other matters, but these were postponed until the next meeting of the Congress, which is to be held in Paris in November.

Something Worthy of Note.... II

The Rules of the Game / La Règle du jeu – IV

The following rules were issued following the meeting in Daytona Beach in December 1947 which established NASCAR, the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing.7 It is interesting and informative to compare the contemporary accounts of what took place in Daytona Beach with what has been passed down and incorporated into the – dare one say “official” – folklore and mythology of NASCAR.

The following rules were approved by the board of governors for the 1948 season.

• Cars eligible-1937 models and up through 1948. '37 and '38 models must have 4-wheel hydraulic brakes. Stock interchangeable passenger car blocks must be used in all cars through 1947.

• Later models must be run in same model chassis.

• Any block can be oversize. The only truck blocks permitted to be used in any stock car will be 100 UP Ford blocks which are fundamentally same as passenger cars. These may only be used in models up to 1947 Ford.

• Piston displacement in any car is limited to 300 cu. in. except where motor is used in same body and chassis it was designed and catalogued for.

• Foreign manufactured cars will not be permitted.

• All cars must have 4-wheel hydraulic brakes or any brake manufactured after 1947.

• Cars may be run with or without the fan or generator.

• Any fly wheel may be used.

• Any part may be reinforced.

• Any interchangeable wheel or tire size may be used.

• Any rear end arrangement may be used.

• Any radiator may be used, providing stock hood will close and latch properly.

• Hoods must have safety straps. All cars must have hoods on and must be stock hood for same model car.

• Any type battery ignition may be used, excluding magnetos.

• Any type of manufactured spark plug may be Used.

• Any model manufactured flat type cylinder heads may be used. Cylinder heads may be machined to increase compression.

• Heads allowed with overhead valves only when coming as standard or optional equipment from factory.

• Any valve springs may be used.

• Multiple carburetion will be permitted.

• Any type carburetion may be used.

• Superchargers allowed only when optional on stock equipment by manufacturer.

• Water pump impellers may be cut down.

• Altered cam shafts will be permitted.

• If car is a convertible type, it must be run with top up and in proper place and must be equipped with safety hoops mounted to frame.

• Any type shock absorber will be permitted.

• All cars must have full stock fenders, running boards and body if so equipped when new, and not abbreviated in any way other than reinforcement.

• All drivers must be strapped in and must wear safety helmets. Belt must be bolted to frame at two points. Must be aviation latch type, quick release belt.

• Regulation crash helmets must be used.

• Stock bumpers and mufflers must be removed.

• Crash bars may be used no wider than frame, protruding no farther than 12 inches from body.

• All doors must be welded, bolted or strapped shut. Doors blocked will not be permitted.

• Fuel and oil capacities may be increased in any safe manner. Any extra or bigger tanks must be concealed inside car or under hood.

• Wheel base, length and width must be stock.

• All cars must have safety glass. All head light and tail light glass must be removed.

• All ears must have full windshield in place and used as windshield. No glass or material other than safety glass may be used.

• Cars must be equipped with rear view mirrors.

• Altered crank shafts may be used.

• The association or representative of same reserves the right to reject any entry for failure to comply with any rules or regulations.

• All tracks must be inspected by technical committee or representative before sanction is granted.

• All cars must be subject to safety inspection by technical committee at any time.

The committee recommended that for the 1949 season, 1937 models be dropped from competition.

Something Worthy of Note.... III

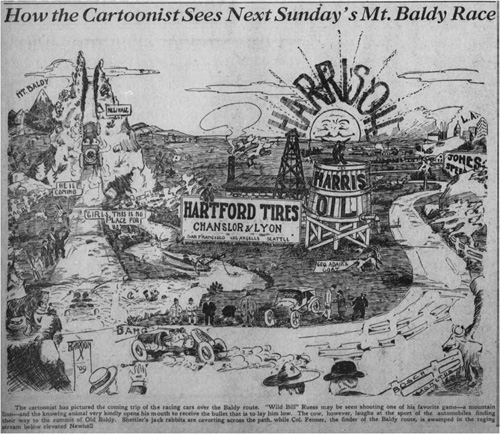

Until recently, I was not aware of the races held from Los Angeles to the foot of Mount Baldy, events that took over a distance of one hundred miles. From what I have gathered, the field was rather small for these events, but they certainly seemed to garner the attention of at least the motorist community in the Southern California region.

The event deserves at least some modicum of attention, given that there seemed to some true personalities involved, several of whom are hinted at in the legend to the cartoon.

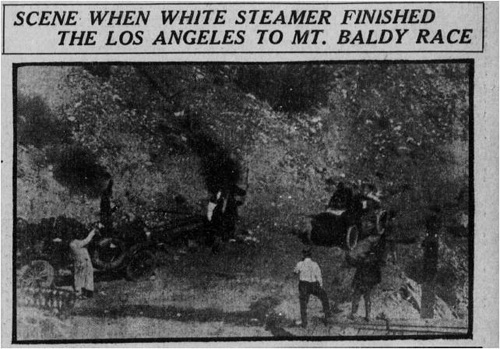

Here is the winner of the 1908 event, the White Steamer, arriving at the finish:

9

Something Worthy of Note.... IV

The Los Angeles to Phoenix races are another set of events which were given what seems to be quite a bit of attention, at least in the pages of the Los Angeles Tribune. The caption for the cartoon was taken, as noted, from a news items regarding the difficulties encountered while negotiating and navigating the distance between the two cities. Thanks in great part to the belated attention that the victory of Barney Oldfield in the 1914 event has gathered, these race series is finally beginning to be given a serious look.

10

Hello, I Must Be Going....

....For Fools rush in where Angels fear to tread

Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism, 1709

Stumbling and Fluttering Forward...

The idea of writing a history of American automobile history has been rattling around in my mind for some time now. Since the appearance of American Automobile Racing, An Illustrated History,11 by Al Bochroch in the early Seventies, to the best of my knowledge there has not been a similar book that has appeared. True, there is American Auto Racing: The Milestones and Personalities of a Century of Speed,12 by James Martin and Tom Saal, but it is really little more than a collection of somewhat related material strung together. Unlike Bochroch, the Martin/Saal is really not a history by any means, at least in my opinion, with a few unfortunate errors that are difficult to overlook.13 Interesting in places, yes. Useful in places, yes.

As I started giving consideration as to how I might go about this task, it seemed to me, after much reflection, that my inclination would be to look a more scholarly work, one that would reflect more the approach of Harold and Dorothy Seymour14 took with their history of baseball than that of a Bochroch-like approach. Naturally, thinking about doing something such as this and then actually doing it are two very separate and distinct propositions.

In his Lectures on the Philosophy of History (Vorlesungen uber die Philosphie der Geschichte), G.W.F. Hegel makes this observation, “Instead of writing history, we are always beating our brains to discover how history ought to be written.” There is also Barbara Tuchman’s warning that, “Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work.” These combine to make the task of writing a history of American automobile racing a distinct challenge.

Some time ago, I considered the problem of just how do you break down the unwieldy time span of automobile racing history, that of the American type in particular, into broad periods, eras, epochs, what have you. Chopping it into small pieces was seemingly easy, but grouping them into some sort larger pieces of time seemed to be more of a challenge than I anticipated. What struck me was that the World Wars seemed to be consistent breaking points, but the more I considered that demarcation point, the less it seemed to fit on a broader scale.

When I worked on developing the outline for what would have become the “American Racing Blue and White” volume in the “Racing Colours” series that Karl Ludvigsen was editing, it struck me that regardless of what others may think that the World Wars really did not work that well when you considered the history, the context, the racing itself. This was the epiphany I was looking for. Once I managed to truly clear my mind of all the preconceived notions and how others had long done it, it began to fall into place.

The first period covers those years up to the 1920 season. Initially, I considered the 1919 season as being the point to end what I refer to with no sense of originality as the “Early Years.” As I thought about and examined the materials, it seemed as if the logical point to end this era was the 1920 season. That any division of the years into smaller clusters is arbitrary, that those years in the cusp of those divisions are usually placed where they are as a “best guess,” it became both easy and logical to use the 1920 season as the anchor for the first era.

The end or anchor point for the second era then became very easy: the 1955 season. The decision by the American Automobile Association to terminate its Contest Board and abandon its role as the national and international sanctioning body for American racing became a logical point to end this period. I had not wanted to have such a dramatic ending for this era, but the logic simply became very clear for doing so the more I pondered the alternatives. Ending the era with the 1941 season and the War ignored the fact that the racing in the immediate post-War years was truly an extension of the pre-War years. Nor did any of several other years work, the impact of 1955 actually becoming crystal clear the more I looked at other seasons. I have not taken the time to give this period a name, referring to it as either the “AAA Years” or the “Boom, Bust, and Renaissance Years.”

Finding a demarcation point for the third period was as challenging as I thought it would be. The season I kept returning to as I considered the possibilities was the 1980 season. In the end, it seemed as good a choice as any given that over the period of several years on either side of this season there were factors that seemed to lend themselves to picking a season was not merely an abrupt, sharp shock to the system as the 1955 season was, but one that was clearly representative of transitions that were taking place. The appearance of the Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), the reorganization of the United States Auto Club (USAC), the attempted compromise of the two organizations, the Championship Racing League, during the 1980 season, the shifts beginning to take place in the other sanctioning bodies, the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA), and the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) led me to think that the 1980 season made sense as the anchor point for the third, unnamed, period of the history of American automobile racing. An additional factor was the increasing role of television, particularly the advent of cable television and the debut of the Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (ESPN), with its appetite for events to fill the hours and hours it now had available.

The last period, imaginatively named the “Modern Era,” begins with the 1981 season and extends to the present.

While certainly open to discussion and modification, I think that these broad, general periods serve their purpose as placeholders, which is their primary function, not being intended as hard and fast boundaries by any means. History does not quite work that way.

As one ponders the problem as just how to go about writing this history of American automobile racing now that the major subdivisions have been determined, it quickly becomes apparent that the more one digs and sifts and sorts the material, the more evident that one’s knowledge is overwhelmed by one’s ignorance as well as beginning to comprehend the difficulties in connecting the dots, putting together the pieces of the puzzle, and then determining just what to leave out. It is this last difficult that is more challenging than is realized. One just keeps finding no end of fascinating material and not quite sure how to integrate into what you think you might wish to say. Then there are all those results for events that seem to lie hidden away that should be made available to those who might be interested in such information.

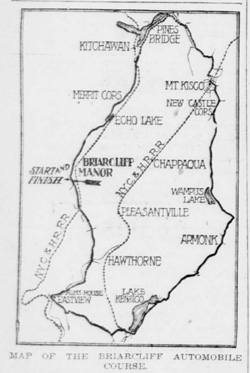

Briarcliff, New York: 1908

Until 1908, road racing in America scarcely existed outside the Vanderbilt Cup and its elimination races. Then in 1908, there were the Savannah road races in March, the Briarcliff race in April, the Denver, Lowell, and Fairmont Park road races in September, the Long Island races in October, to include the Vanderbilt Cup, and the Los Angeles to Phoenix and Savannah races in November, as well as a number of hill climb events scattered throughout the season. In 1907, there had not been a running of the Vanderbilt Cup, so, outside the hill climbs, there was no racing on the roads of any significance.

While one may speculate as to why road racing seemed to suddenly emerge during the 1908 season, it was probably due to a combination of factors, rather than any single factor or even just several factors. Whatever the reasons for this shift, road racing would continue as a major form of racing in America until the 1916 season. Not until two world wars later would road racing once again emerge as a major factor on the American racing scene.

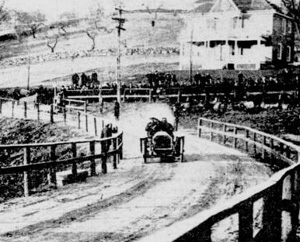

Lewis Strang crossing the finish line in the J.H. Tyson Isotta-Franchini to win the Briarcliff Trophy on 24 April 1908.15

The Briarcliff Trophy race of April 1908 fell in the midst of the opening stages of the spat between the Automobile Club of America (A.C.A.) and the American Automobile Association (A.A.A.). By April, the A.C.A. had already served its notice to the A.A.A. and there had been the successful road race in Savannah. However, the Briarcliff was to take place in what was still the heart of American racing: the environs of New York.

Here are several photographs taken during the practice sessions that provide a good idea as to the nature of the course:

16/17

Sheepshead Bay: 1910

Jack Johnson and Barney Oldfield at the Sheepshead Bay Track for their match race on 25 October 1910.18

In the middle of what can only be described as one of the worst periods for Black Americans in recent history, the emergence of Jim Crow at the turn of the Twentieth Century, there was one man who seemed to stand in the way: Jack Johnson. Here is a photograph taken during the match race that Johnson and Oldfield had at the Sheepshead Bay Track in Brooklyn. Oldfield was suspended until 1912 as a result of this event.

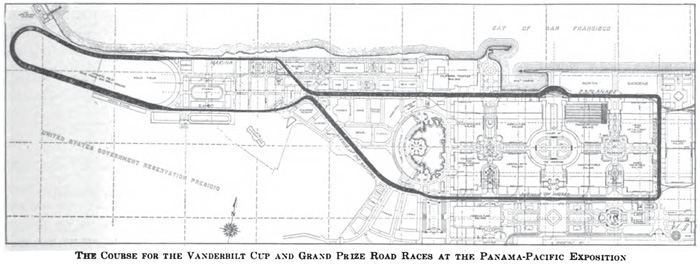

San Francisco, 1915: The A.C.A. Grand Prize for the Gold Cup and Vanderbilt Cup Races

The last years of both the Grand Prize of the Automobile Club of America and the Vanderbilt Cup were spent in the West, the last three years on the West Coast. After the 1911 races in Savannah, the two events moved first to Milwaukee in 1912, then Santa Monica in 1914, San Francisco in 1915, and back to Santa Monica in 1916.

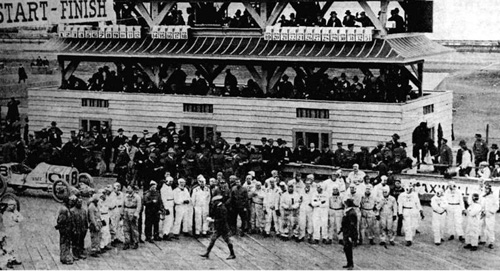

The drivers and their mechanicians on the grid for the Grand Prize event. Note the planked board surface which covered the track that ringed the polo field section of the race course.

The starting grid for the Grand Prize event.

The starting grid for the Vanderbilt Cup event.

1920 Savannah Road Race

Although the “Great Savannah Races” of 1908, 1910 and 1911 – with the running of the Grand Prize and Vanderbilt Cup events, seem to have garnered much attention, there were other races were in the Savannah area during this general period as well. At some point there was a three hundred mile road race run in Savannah for motorcycles, with Bob Perry in an Excelsior winning over the Harley-Davidson of Maldwyn Jones. In addition, there were another set of road races run in Savannah on Thanksgiving Day 1920. I have not been able to gather much information on these Thanksgiving Day events, but here is what little I have so far.

Sanction No. 1230

Savannah, Georgia / Road Race

25 November 1925

Course: approximately three miles

Promoter: Savannah Automobile Club

A.A.A. Representative: E.M. Lokey Referee: J.R. O’Neill Chief Timer: Dr. J.E. Hodge

Chief Scorer: J.R. Christian Assistant Scorers: John S. Balmer, E.J. Best, J.O. Johnson, J.G. O’Neill, J.S. Cofiero

First Race / Class D / Free for All / 10 laps, approximately 30 miles

| 1st | C.B. Humbert, No. 2 Packard Special | 29 min 17.00 sec |

| 2nd | H.L. Capps, No. 12 Dodge Special | 30 min 30.00 sec |

| 3rd | Drossopoilos, No. 6 Chalmers Special | 30 min 38.00 sec |

| 4th | Bruckner, No. 19 Buick Special | 30 min 45.00 sec |

| 5th | Austin, No. 13 Stephens Special | 32 min 17.00 sec |

| 6th | Rivers, No. 10 Essex Special | 32 min 18.00 sec |

| 7th | Kuck, No. 11 Mercer Special | 34 min 03.00 sec |

| 8th | Steel, No. 3 Chalmers Special | 34 min 26.00 sec |

| Morris, No. 15 Oldsmobile Special | Flagged | |

| Collins, No. 9 Chalmers Special | Flagged | |

| Miles, No. 16 Chalmers Special | Flagged | |

| J.L. Humbert, Lexington Special | Out, 6th lap | |

| Schwartz, No. 1 Monroe Special | Out, 1st lap | |

| Hudson, No. 14 Elcar Special | Out, 1st lap | |

| Tison, No. 8 Cadillac Special | Out, 1st lap | |

| Douglass, No 17 Hudson Special | Disqualified |

Second Race / Class D / Free for All / 15 laps, approximately 45 miles

| 1st | C.B. Humbert, No. 2 Packard Special | 47 min 52.00 sec |

| 2nd | Drossopoilos, No. 6 Chalmers Special | 50 min 30.00 sec |

| 3rd | Bruckner, No. 19 Buick Special | 50 min 33.00 sec |

| 4th | Kuck, No. 11 Mercer Special | 51 min 30.00 sec |

| 5th | Brewer, No. 18 Buick Special | 52 min 58.00 sec |

| 6th | Austin, No. 13 Stephens Special | 53 min 42.00 sec |

| 7th | Rivers, No. 10 Essex Special | 53 min 45.00 sec |

| Miles, No. 16 Chalmers Special | Out, 14th lap | |

| Steel, No. 3 Chevrolet Special | Out, 14th lap | |

| H.L. Capps (Neal Bolton), No. 12 Dodge Special | Wrecked, 10th lap19 | |

| Tison, No. 8 Cadillac Special | Out, 9th lap | |

| Collins, No. 9 Chalmers Special | Out, 8th lap | |

| Morris, No. 15 Oldsmobile Special | Out, 1st lap |

Flag Codes: 1929 and 1930

The 7 March 1929 issue of the Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (Volume IV, No. 7) proposed changes to the current flag code being used by the A.A.A. for its flags.

The 1929 flag code was as follows:

Red Flag – Course is clear.

Yellow Flag – Blocked course; slow.

Green Flag – You are entering your last lap.

White Flag – Stop at pit on next lap for consultation.

Black and White Checkered Flag – You are finished.

Black Flag with White Center – A competitor is trying to overtake you.

The proposed changes:

Green Flag – Start or go.

Blue Flag – Pull over, competitor is trying to pass you.

Red Flag (stationary) – Caution – watch out for conditions ahead; get your car under control – bad conditions ahead.

Red Flag (waved) – Slow down still farther.

Black Flag – Stop next lap for consultation.

White Flag – You are entering your last lap.

Checkered Flag – You are finished.

The responses led to a modified proposal in the 30 April 1929 edition of the Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (Volume IV, No. 12):

Green Flag – Start; course in clear.

Yellow Flag – Caution; watch out for conditions ahead; get your car under control and hold your position.

Red Flag – Stop – race is halted.

White Flag – Stop next lap for consultation.

Blue Flag with White Center – Competitor is trying to overtake you.

Black Flag – You are entering your last lap.

Checkered Flag – You are finished.

The 19 February 1930 edition of the Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (Volume IV, No. 31), on page 4, the following appeared:

Change in Flag Codes

The following flags are in effect and will govern during the coming season:

Green Flag – Start; course is clear.

Yellow Flag – Caution; watch out for conditions ahead – get your car under control AND HOLD YOUR POSITION.

Red Flag – Stop – race in halted.

White Flag – Stop next lap for consultation (to driver designated).

Orange Flag with Navy Blue Center – Competitor is trying to overtake you.

King Blue Flag - You are entering your last lap.

Checkered Flag – You are finished.

Stock Car Racing Genesis: The 1936 Daytona Road and Beach Race and the 1939, 1940, and 1941 Langhorne Stock Car Races

Daytona Beach, 1936

On 8 March 1936, the City of Daytona held a race scheduled for just over 250 miles underSanction No. 3334 issued by the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association. The event was run over a 3.2-mile course which utilized the southern beach area and the road paralleling the oceanfront area. While much has been made in the years over this event being the “birth” of stock car racing and NASCAR (National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing), one could suggest that such claims are rather wide of the mark. Due to tidal conditions, the race was halted after the leading car completed 75 laps, 240.2 miles.

There seems to be only one in-depth look at this event, that of NASCAR chronicler and historian Greg Fielden in his book on the Daytona road and beach races, High Speed at Low Tide,20 which does provide an excellent account of the background to this event, as well as subsequent races.

The loss of the annual visits by the record breakers to the Ormond-Daytona beaches in late Winter in 1935 after over three decades of such activity, spurred the business and civic leaders of Daytona Beach to find another means to fill the gap for the now-departed “Speed Weeks.” The idea of using the beach and parallel roads surfaced early on, the original suggestion of Sig Haugdahl for an eight-mile course – four miles respectively of beaches and roads, was initially shorted to about five miles, until the 3.2-mile road and beach course was finally decided upon.

The real innovation was to hold the event for “stock cars,” a category of racing that had dropped to the lower ranks of automobile racing during the Twenties and Thirties in the United States, there being very few events run for such cars after the end of The Great War in 1918. However, this was not a category of cars very far from both the attention of the public and the racing community. The race for stock cars held in 1927 at the Atlantic City Speedway in Amatol, New Jersey, was still remembered, as well as the use of stock cars for the revival of the Elgin Road Races just a few years earlier. In addition, there were events for stock cars being conducted in California.

Attention must also be directed towards some of the consequences that could be considered as a result of the so-called “Junk Formula” which was adopted for the running of the annual International 500 Mile Sweepstakes at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. This was an effort to entice the manufacturers back into racing, an idea that while having mixed results, it did manage to draw the attention of a few of the manufacturers to the point where plans were made and teams were entered in several cases. It also seems to have encouraged the further development of what became known as “speed equipment” for those wishing to modify their cars for higher performance. The introduction of the “Flathead” Ford V-8 in the early Thirties also played a role in what became known as “hot-rodding.” That many of these performance parts were available through mail order, was also another factor that should be considered.

The event was open to 1935 and 1936 models of American manufacture, with the cars being “strictly stock,” with the provision that the bumpers could be removed being the only real provision for racing. The cars had to carry a spare tire and the windshield had to be in place.

What is generally overlooked regarding this race is that it was run using a handicap system. The 16 March 1936 issue of the Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (Volume XI, Bulletin 2), provides a rundown of the way the handicap set the time for the cars to begin the race.

| No. / Make | Driver | Qualifying Time | Mph | Handicap | Starting Time |

| 4 / Willys 77 | Sam Collier | 3m 18.26s | 58.60 | 40m 29s | 00h 00m 00s |

| 1 / Willys 77 | Langdon Quinby | 3m 16.23s | 58.71 | 38m 06s | 00h 02m 29s |

| 5 / Dodge | Bill Schindler | 3m 13.13s | 59.65 | 34m 29s | 00h 02m 37s |

| 3 / Chevrolet | B.J. Gibson | 3m 07.40s | 61.47 | 27m 45s | 00h 02m 55s |

| 6 / Ford V-8 | Bob Sall | 3m 07.26s | 61.51 | 27m 37s | 00h 03m 03s |

| 7 / Lincoln Zephyr | A.T.G. Gardner | 3m 06.53s | 61.76 | 26m 45s | 00h 03m 55s |

| 26 / Ford V-8 | Tommy Elmore | 3m 04.96s | 62.28 | 24m 55s | 00h 05m 45s |

| 8 / Ford V-8 | Gil Farrell | 3m 03.70 | 62.71 | 23m 27s | 00h 07m 13s |

| 9 / Ford V-8 | Bill Lawrence | 3m 03.40s | 62.81 | 23m 05s | 00h 07m 35s |

| 10 / Ford V-8 | Bill France | 3m 02.86s | 62.99 | 22m 21s | 00h 08m 19s |

| 11 / Ford V-8 | Lou Campbell | 3m 01.96s | 63.31 | 21m 25s | 00h 09m 15s |

| 12 / Ford V-8 | Al Pierson | 3m 01.26s | 63.55 | 20m 36s | 00h 10m 04s |

| 14 / Ford V-8 | Walter Johnson | 3m 00.20s | 63.92 | 19m 21s | 00h 11m 19s |

| 15 / Ford V-8 | Dan Murphy | 3m 00.10s | 63.96 | 19m 15s | 00h 11m 25s |

| 16 / Ford V-8 | Al Cusick | 2m 59.33s | 64.23 | 18m 19s | 00h 12m 21s |

| 17 / Ford V-8 | Ed Eng | 2m 59.26s | 64.26 | 18m 15s | 00h 12m 25s |

| 25 / Ford V-8 | Al Wheatley | 2m 56.63s | 65.22 | 15m 10s | 00h 15m 30s |

| 29 / Auburn | John Rutherford | 2m 54.63s | 65.96 | 12m 50s | 00h 17m 50s |

| 18 / Ford V-8 | Ben Shaw | 2m 54.50s | 66.01 | 12m 40s | 00h 18m 00s |

| 23 / Ford V-8 | Milt Marion | 2m 54.10 | 66.16 | 12m 13s | 00h 18m 27s |

| 28 / Ford V-8 | Virgil Mathis | 2m 53.80s | 66.28 | 11m 52s | 00h 18m 48s |

| 20 / Oldsmobile | Ken Schroeder | 2m 53.73s | 66.30 | 11m 47s | 00h 18m 53s |

| 19 / Ford V-8 | Sam Purvis | 2m 51.33s | 67.23 | 08m 58s | 00h 21m 42s |

| 24 / Ford V-8 | “Doc” MacKenzie | 2m 49.66s | 67.90 | 07m 01s | 00h 23m 19s |

| 22 / Ford V-8 | C.M. “Hick” Jenkins | 2m 49.52s | 67.95 | 06m 51s | 00h 23m 29s |

| 27 / Ford V-8 | Jack Holly | 2m 49.30s | 68.04 | 06m 04s | 00h 24m 04s |

| 2 / Auburn | Bill Cummings | 2m 43.66s | 70.39 | Scratch | 00h 30m 40s |

There was a stipulation that should a car lap faster than the time set during the qualifying runs by a margin of three miles per hour, the car would be disqualified, a measure that was meant to eliminate “sandbagging.”

The qualifying and practice runs quickly made it apparent that the turns could be a greater difficulty than many had imagined. Bob Sall lost control of his Ford convertible in the soft sand while approaching one of the turns, being ejected from the car and then being rushed to the hospital since it was believed he had to have suffered serious injuries from the crash. Amazingly enough, Sall only suffered minor injuries and was able to participate in the race.

One problem prior to the race was that while the organizers, the City of Daytona, had sold enough tickets and raised enough money to cover the prize monies being offered, there had been problems with ticket sales and then would have consequences for future events. The exact number of spectators is not known, but of the 20,000 or so claimed, it is doubtful that many paid to watch the race.

The first car, the Willys 77 of Sam Collier, was waved off at exactly One o’clock p.m., with the others departing at the designated intervals determined by the handicap, the Auburn of fastest qualifier “Wild Bill” Cummings not departing until 30 minutes and 40 seconds later. The staggered start due to the handicapping system did make it difficult for both spectators and participants alike to be sure who was in what position during most of the race.

Although it had been announced as part of the supplementary rules that outside assistance would result in disqualification, the reality of the surface breaking up in the two turns led to this being generally ignored, efforts to clear the turns of bogged down cars outweighing the rules. The North Turn fared much worse than the South Turn did as the race went on, although both were difficult to negotiate by the end of the race.

Just as it would be decades later for other races, scoring the event proved difficult. As the laps to the finish wound down, there was some question as to who was in which position, although it appeared to be Milt Marion. As the pace of the race was slower than anticipated, the tide began to come in and the race was halted several laps short of the 250-mile mark. Both the second and third place finishers, Ben Shaw and Tommy Elmore, thought that they were the winner of the race. Elmore, from Jacksonville, had been among the quickest during the race, but a lap down to Marion and three seconds to Shaw. Although Elmore filed a protest, it was rejected and he had to settle for third. Subsequent events would not use the handicap system.

| Finish | No. | Driver | Make | Laps | Remarks |

| 1st | 23 | Milt Marion | Ford | 75 | $1,700 |

| 2nd | 18 | Ben Shaw | Ford | 74 | $1,000 |

| 3rd | 26 | Tommy Elmore | Ford | 74 | $750 |

| 4th | 19 | Sam Purvis | Ford | 70 | $500 |

| 5th | 10 | Bill France | Ford | 63 | $400 |

| 6th | 22 | Hick Jenkins | Ford | 60 | $300 |

| 7th | 4 | Sam Collier | Willys 77 | 57 | $200; credited with 3 laps at start |

| 8th | 16 | Al Cusick | Ford | 49 | $100 |

| 9th | 25 | Al Wheatley | Ford | 44 | $50 |

| 10th | 17 | Ed Eng | Ford | 44 | $50 |

| 11th | 28 | Virgil Mathis | Ford | 60 | retired |

| 12th | 15 | Danny Murphy | Ford | 59 | retired |

| 13th | 20 | Ken Schroeder | Oldsmobile | 54 | retired |

| 14th | 27 | Jack Holly | Ford | 48 | retired |

| 15th | 7 | A.T.G. Gardner | Lincoln Zephyr | 45 | retired |

| 16th | 9 | Bill Lawrence | Ford | 44 | retired |

| 17th | 1 | Langdon Quinby | Willys 77 | 39 | retired; credited with 2 laps at start |

| 18th | 5 | Bill Schindler | Dodge | 38 | retired; credited with 2 laps at start |

| 19th | 12 | Al Pierson | Ford | 35 | retired |

| 20th | 8 | Gil Farrell | Ford | 33 | retired |

| 21st | 14 | Walter Johnson | Ford | 29 | retired |

| 22nd | 11 | Lou Campbell | Ford | 27 | retired |

| 23rd | 29 | Jack Rutherford | Auburn | 26 | retired |

| 24th | 24 | Doc MacKenzie | Ford | 25 | retired |

| 25th | 6 | Bob Sall | Ford | 24 | retired |

| 26th | 2 | Wild Bill Cummings | Auburn | 16 | retired |

| 27th | 3 | B.J. Gibson | Chevrolet | 10 | retired |

The City of Daytona lost money of the 1936 race. The usual figure given is approximately $22,000, a great deal of money in 1936. Any enthusiasm that the town had for further promotion of automobile racing quickly died when the magnitude of the losses became apparent.

Others picked up the idea for racing on the combined road and beach course and events were held right up until the beginning of the Second World War. Here is a listing of the winners for the events from 1937 until 1941:

1937 / 5 September – Carl “Smokey” Purser, No. 4 Ford

1938 / 10 July – Danny Murphy, No. 25 1938 Ford

1938 / 5 September – Bill France, No. 3 1937 Ford

1939 / 19 March – J. Sam Rice, No. 5 1939 Mercury

1939 / 4 July – Stewart Joyce, No. 1 1932 Ford

1939 / 4 September – Carl “Smokey” Purser, No. 2 1939 Mercury

1940 / 10 March – Roy Hall, No. 14 1939 Ford

1940 / 7 July – Bill France, No. 14 1939 Buick

1940 / 2 September – Buck Mathis, No. 8 1934 Ford

1941 / 2 March – Roy Hall, No. 14 1939 Ford

1941 / 30 March – Carl “Smokey” Purser, No. 2 1939 Ford

1941 / 27 July – Bernard Long, No. 9 1940 Mercury

1941 / 24 August – Lloyd Seay, No. 7 1940 Ford

There were other stock car races run in the South during the years immediately prior to the War. If one digs hard enough, mention of these races can be found. Many would be surprised to find that Harley Taylor, of Atlanta, won the 100-lap event at the Southeastern States Fairgrounds in Charlotte on 4 July 1941, his time beating the previous “world record” of Lloyd Seay which was sat at Allentown on 20 May 1941. Although Fontello Flock “nosed out” Jap Brogdos of Chamblee for second, Jimmy Lou Moore, of High Point, is listed as finishing third.

As many have discovered, sorting out the history stock car racing is not a task for the faint-hearted or the thin-skinned. The folklore, legend, and mythology that has enveloped the early days of stock car racing, generally given as the Thirties, and tied it to the moonshiners has become such an article of faith to so many that to even question it, to cast open doubt, to challenge this dogma, is one sure way to be the target of their ire and the recipient of their spiteful comments. Of course, as a historian, one must simply shrug it off and continue to march to the sound of the facts. That one considers those clinging to that mythology as having all the smarts of a box of rocks goes without saying.

Langhorne

In 1939,22 1940,23 and 1941,24 there were 200-mile events for “strictly stock cars” held at the Langhorne Speedway in Pennsylvania. The Contest Board of the A.A.A. issued “Special Bulletins” on two of these events25 as an indication of the attention the Contest Board was beginning to pay stock car racing. The Sanction No. for 1939 was 3693 and 3806 for 1940.

Langhorne, 1939

The 1939 event was held of 26 July and limited to forty starters and open to 1937, 1938, and 1939 models of American manufacture. The cars had to be “strictly stock,” but in the interest of safety the following could be removed: front and rear bumpers and mounting brackets, hub caps, and headlight lenses. The use of regular gasoline was required. There would be a paced start to the race. According to the Contest Board Bulletin, the qualifying for the event was in the form of two ten-mile qualifying heats held on Sunday, 25 June and 2 July. However, the qualifying was carried out in a series of ten-mile heats on each day, those on the first day filling the 20 positions on the inside row and the later qualifiers filling the remaining positions on the outside row.

The pole was won by Ted Nyquist, the winner of the “fast car” heat on 25 June, leading all 10 of the laps in the heat. He was followed across the line by Walt Keiper, Walt Franks, and George “Red” Lapworth. The second heat was won by Johnny Cebula, who barely edged out Bill Holland in what was almost a dead heat. They were followed by Shoop and Schmieder. The third heat was won by Bill McCarthy, followed by Milt Marion, the Daytona Beach winner, Cooney and Smith. This heat had the Nash of Bill Madden lose a wheel and veer towards the pits threatening personnel working in the pit, both the car and the wheel not causing any harm.

The fourth heat went to the Cooper, followed by Toner, Hickey, and Rogers. The fifth and final heat, according to Riggs, went to Menendez. However, this heat was probably run on the second date set aside for qualifying, 2 July, rather than the first weekend since Menendez occupied the 35th starting position on the grid.

The heats were apparently composed of up to six starters, with the first four qualifying for the feature race on 4 July. We have a photograph of one of the heats showing six starters, with Hemingway on the pole, flanked by the Ford Deluxe of Bob Rhoades, with Julien and Mike Felber, 1939 Plymouth, in the second row and the third row Bob Basker in a 1937 Graham, along with an unidentified 1939 Ford.

The breakdown of the qualifiers by make:

| Ford V-8 | 19 | (1939 nine, 1938 six, and 1937 four) |

| Mercury | 4 | (all 1939 models) |

| Buick | 4 | (1939 two, 1938 two) |

| Dodge | 2 | (1939) |

| Studebaker | 2 | (1939 Champion and 1937 President) |

| Hudson | 2 | (1939 and 1938) |

| Willys-Overland | 1 | (1939) |

| Oldsmobile | 1 | (1939 “8”) |

| Plymouth | 1 | (1939) |

| Packard | 1 | (1939) |

| Nash | 1 | (1937) |

| Graham | 1 | (1937) |

| Lincoln Zephyr | 1 | (1939) |

Here is the starting grid for the event:

| Pole | Outside | |

| Row 1 | No. 5, Nyquist, Oldsmobile | No. 28, Stanley, Ford |

| Row 2 | No. 4, Keiper, Ford | No. 26, Elmore, Ford |

| Row 3 | No. 2, Franks, Ford | No. 21, Hall, Ford |

| Row 4 | No. 15, Lapworth, Mercury | No. 25, Rice, Mercury |

| Row 5 | No. 12, Cebula, Hudson | No. 44, Banks, Buick |

| Row 6 | No. 14, Holland, Mercury | No. 32, Beam, Ford |

| Row 7 | No. 18, Shoop, Buick | No. 1, Purick, Mercury |

| Row 8 | No. 9, Schmeider, Ford | No. 37, Frerichs, Lincoln |

| Row 9 | No. 27, McCarthy, Ford | No. 43, Warke, Ford |

| Row 10 | No. 23, Marion, Ford | No. 52, McMahon, Mercury |

| Row 11 | No. 20, Cooney, Ford | No. 47, Beckett, Ford |

| Row 12 | No. 34, Smith, Packard | No. 45, Hickman, Ford |

| Row 13 | No. 40, Cooper, Buick | No. 22, Baker, Graham |

| Row 14 | No. 11, Toner, Ford | No, 48, Hemingway, Hudson |

| Row 15 | No. 29, Hickey, Ford | No. 16, Felber, Plymouth |

| Row 16 | No. 36, Rogers, Dodge | No. 35, Menendez, Dodge |

| Row 17 | No. 41, Russell, Ford | No. 3, Ross, Willys-Overland |

| Row 18 | No. 39, Julien, Ford | No. 6, Madden, Nash |

| Row 19 | No. 46, Cusick, Studebaker | No. 8, Simins, Studebaker |

| Row 20 | No. 53, Hicks-Beach, Ford | No. 55, Light, Buick |

In the race, Nyquist took an early lead until forced to pit due to a flat left front tire. Nyquist lost several laps in the pits while the tire was being replaced. Keiper had the lead for several laps before being passed by Bill McCarthy, with a flurry of lead changes coming between the 71st and 83rd laps, Bill Shoop taking the lead for a period. The contest seemed to be shaping up as one between Keiper, Shoop, and Banks, but Light, who started from the back row, was tearing through the field.

There were surprisingly few retirements in the race, the wreck of Menendez being the only notable wreck of the event, the Dodge rolling several times, but the driver emerging unharmed. When the race resumed after this accident, Shoop apparently got the jump on Banks and took the lead until the checkered flag. However, as it turned out, the winner was actually Light. In addition this, Nyquist was convinced that he was the winner. The review of the scoring sheets took several days and the results as announced left several seething.

According to the official scoring sheets, by the three-quarter mark of the race, Light was able to take the lead from Keiper, only to lose it to Banks for several laps, before taking it over for good on lap 157. Despite losing several laps very early in the race, Nyquist managed to finish sixth place at the end, unlapping himself several times and he roared through the field.

While the Contest Board and others reserved judgment concerning stock car racing, the race did bring stock car racing back into the limelight, even if only temporarily. What seems to have been one concrete result of the event was that it proved that there was both an interest in stock car racing and that it was popular, the track having a good turnout for the event.

| Finish | No. | Driver | Make | Remarks |

| 1st | 55 | Mark Light | 1939 Buick Century 60 | 200 laps, 3 hr 03 min 39 sec, 65.5 mph |

| 2nd | 4 | Walt Keiper | 1938 Ford | 200 laps |

| 3rd | 3 | Bert Ross | 1939 Willys-Overland | 200 laps |

| 4th | 44 | Henry Banks | 1938 Buick 60 | 200 laps |

| 5th | 18 | Bill Shoop | 1939 Buick 40 | 200 laps |

| 6th | 5 | Ted Nyquist | 1938 Oldsmobile 8 | 200 laps |

| 7th | 16 | Mike Felber | 1939 Plymouth | 200 laps |

| 8th | 37 | J.F. Frerichs | 1938 Lincoln Zephyr | 200 laps |

| 9th | 29 | Ken Hickey | 1938 Ford | 200 laps |

| 10th | 34 | Frank Smith | 1939 Packard 120 | Flagged on 198th lap |

| 11th | 20 | Bob Cooney | 1937 Ford | Flagged on 198th lap |

| 12th | 47 | L. Beckett | 1937 Ford | Flagged on 197th lap |

| 13th | 36 | John Rogers | 1939 Dodge | Flagged on 197th lap |

| 14th | 43 | Buster Warke | 1938 Ford | Flagged on 196th lap |

| 15th | 21 | Roy Hall | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 195th lap |

| 16th | 27 | Bill McCarthy | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 195th lap |

| 17th | 53 | John Hicks-Beach | 1938 Ford | Flagged on 194th lap |

| 18th | 11 | Tom Toner | 1938 Ford | Flagged on 192nd lap26 |

| 19th | 8 | Metz Simins | 1939 Studebaker Champion | Flagged on 190th lap |

| 20th | 25 | John Rice | 1939 Mercury | Flagged on 188th lap |

| 21st | 9 | Walt Schmeider | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 183rd lap |

| 22nd | 28 | Pete Stanley | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 182nd lap |

| 23rd | 41 | Jack Russell | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 181st lap |

| 24th | 23 | Milt Marion | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 181st lap27 |

| 25th | 45 | Joe Hickman | 1937 Ford | Flagged on 180th lap |

| 26th | 39 | Joseph Julien | 1937 Ford | Flagged on 176th lap |

| 27th | 40 | Manuel Cooper | 1938 Buick 60 | Flagged on 174th lap |

| 28th | 14 | Bill Holland | 1939 Mercury | Flagged on 173rd lap |

| 29th | 46 | Al Cusick | 1937 Studebaker President | Flagged on 170th lap |

| 30th | 26 | Tommy Elmore | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 170th lap |

| 31st | 32 | George Beam | 1939 Ford | Burnt rod on 145th lap |

| 32nd | 6 | Bill Madden, Jr. | 1937 Nash 6 | Flagged on 131st lap |

| 33rd | 35 | Frank Menendez | 1939 Dodge | Wrecked on 123rd lap |

| 34th | 52 | Ray McMahon | 1939 Mercury | Blown head gasket on 120th lap |

| 35th | 2 | Walt Franks | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 119th lap |

| 36th | 1 | Honey Purick | 1939 Mercury | Flagged on 116th lap28 |

| 37th | 15 | George Lapworth | 1938 Ford | Wrecked on 74th lap |

| 38th | 48 | Cliff Hemingway | 1938 Hudson 6 | Broken steering arm on 73rd lap |

| 39th | 22 | Bob Baker | 1937 Graham 6 | Flagged on 71st lap |

| 40th | 12 | Johnny Cebula | 1937 Hudson 8 | Cracked cylinder head on 25th lap |

There were a total of 161 pit stops made during the race, it being noted that many were related to adding water since the air temperature during the race was in the high-80’s Fahrenheit. The fastest lap of the race was set on the second lap by the pole-sitter, Ted Nyquist, in his Oldsmobile, the speed being given as 71.77 mph.

Here is a breakdown of the lap leaders:

| Laps | Driver |

| 1 – 29 | Nyquist, Oldsmobile |

| 30 – 33 | Keiper, Ford |

| 34 – 70 | McCarthy, Ford |

| 71 – 73 | Lapworth, Ford |

| 74 & 75 | Keiper, Ford |

| 76 & 77 | Banks, Buick |

| 78 – 82 | Ross, Willys-Overland |

| 83 – 111 | Shoop, Buick |

| 112 – 130 | Keiper, Ford |

| 131 – 138 | Banks, Buick |

| 139 – 144 | Keiper, Ford |

| 145 – 149 | Light, Buick |

| 150 – 156 | Banks, Buick |

| 157 – 200 | Light, Buick |

Langhorne, 1940

The 1940 event was held on 4 August 1940. The A.A.A. representative for the race was Joseph C. Dawson, the Zone Supervisor and a member of the A.A.A. Contest Board. The models eligible for the 1940 event were 1938, 1939, and 1940 regular models of American manufacture which would race in “strictly stock” form. As in 1939, the A.A.A. Technical Committee allowed the following modifications to the automobiles participating: the front and rear bumpers and mounting brackets were to be removed; hub caps and headlight lenses were also to be removed; mufflers could be removed at the option of the competitor, but there was still the requirement for a full-length tail pipe to be installed. The starting field was reduced from 40 to 36.

Time trials, according to the Contest Board Bulletin, for the 1940 event were held on 28 July and 3 August in the form of ten-mile heats. During one of the qualifying heats, Hugh Davis, of Richmond, died as the result of head injuries suffered when thrown from his car when it crashed, flipping and rolling several times.

The first qualifying heat was won by Mark Light, followed by Walt Keiper, Henry Banks, and Ted Nyquist. The second heat was won by Ebby Ebersole, with Bob Irwin second, but the third place of Jeff Frame was notable because he started in 11th place in a 12-car field to achieve that placing. Ottis Stine was fourth. In the next heat, the third, Harold Brokhoff performed a similar feat, beginning the race deep in the field and not only taking the lead, but pulling away from the field. Brokhoff was followed by McCarthy, Zarka, and Strauss. The fourth heat went to Bailey, followed by Stonebreaker, Elkie Montgomery, and Huskey. The fifth heat was won by McCaskill with the Blatt Mercury in second.

The winners of the five heats on 3 August were: Cramer, Ashbaugh, Chitwood, Elmore, and Winnai

.The breakdown of qualifiers by make for the 1940 race:

| Buick | 15 | (1940 four, 1939 nine, and 1938 three) |

| Ford | 13 | (1940 five, 1939 five, and 1938 three) |

| Chrysler | 1 | (1938) |

| De Soto | 1 | (1940) |

| Lincoln Zephyr | 1 | (1940) |

| Mercury | 1 | (1940) |

| Oldsmobile | 1 | (1939) |

| Pontiac | 1 | (1939) |

| Studebaker | 1 | (1940) |

| Willys | 1 | (1940) |

The announced attendance for the race was 37,799 spectators. The weather was hot, humid, and with still winds, making the heat seem even more intense. On the first very corner of the first lap, the winner of the previous year’s race, Mark Light, along with Banks and Ross, all tried to squeeze into the same space, with the result being that the race was over for Light when he hit the fence and heavily damaged his car. Banks was sent to the rear of the pack, in 35th position, as a result of the incident.

When the green flag was waved to resume racing, the lead was taken by Bill France, but he was soon passed by Saylor, with Nyquist in second place. When the steering on the Saylor Ford failed, he crashed at Puke Hollow, ending up in the drainage ditch inside the track. Nyquist then took the lead. However, Banks was roaring through the pack, and was soon in second place. When Nyquist pitted due to overheating, Banks took the lead until pitting, Russell then becoming the race leader.

By mid-race, the track was in poor shape, the dust being very bad. Banks quickly caught and passed Russell to retake the lead, just past the half-way of the race, the 103rd lap. Banks would lead the race until the checkered flag fell, none of the others being able to challenge him.

After the race, France filed a protest on the Sherman “Red” Crise-owned Buick. The car was found to be legal, but post-race inspections did result in the disqualification of the cars that were originally placed third and fourth due to using non-stock sized tires and a Mercury engine in a Ford, respectively.

| Finish | No. | Driver | Make | Remarks |

| 1st | 25 | Henry Banks | 1939 Buick 66S | 200 laps |

| 2nd | 14 | Bill Frank | 1939 Buick 68 | 200 laps |

| 3rd | 11 | Walt Keiper | 1939 Buick 66S | 200 laps |

| 4th | 40 | Joie Chitwood | 1940 Buick 60 | 200 laps |

| 5th | 53 | John Hicks-Beach | 1938 Ford | 200 laps |

| 6th | 21 | Jack Russell | 1939 Ford | 200 laps |

| 7th | 50 | Tony Willman | 1939 Buick Special | 200 laps |

| 8th | 10 | Bert Ross | 1940 Willys 440 | 200 laps |

| 9th | 1 | Ted Horn (with relief driver) | 1940 Lincoln Zephyr | 200 laps |

| 10th | 35 | Harold Brokhoff | 1940 Buick 60 | Flagged on 197th lap |

| 11th | 59 | Albert Garz (with relief driver) | 1938 Chrysler Royal | Flagged on 191st lap |

| 12th | 26 | Tillman Husky | 1940 Ford | Flagged on 189th lap |

| 13th | 49 | Fred Winnai | 1940 De Soto | Flagged on 182nd lap |

| 14th | 44 | James Stonebreaker | 1938 Ford | Wrecked on 181st lap |

| 15th | 47 | Buddie Rusch | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 175th lap |

| 16th | 58 | Mac MacKenzie | 1939 Ford | Flagged on 158th lap |

| 17th | 51 | Jack McCaskill | 1939 Pontiac 8 | Wrecked on 142nd lap |

| 18th | 18 | Tom Hinnershitz | 1939 Buick 41 | Water in gas on 137th lap |

| 19th | 8 | Bob Sall | 1938 Buick 60 | Cracked cylinder head on 114th lap |

| 20th | 39 | Frank Bailey | 1939 Buick 60 | Out on 113th lap |

| 21st | 5 | Ted Nyquist | 1939 Oldsmobile | Hit wheel thrown by another car on 109th lap |

| 22nd | 31 | Jeff Frame | 1940 Buick 76S | Blown head gasket on 94th lap |

| 23rd | 41 | Robert Apperson | 1940 Ford | Cracked cylinder head on 85th lap |

| 24th | 4 | Everett Saylor | 1938 Ford | Hit fence on 64th lap |

| 25th | 48 | Irvin Blatt | 1940 Mercury | Wrecked on 47th lap |

| 26th | 17 | Gus Zarka | 1940 Buick | Seized engine on 46th lap |

| 27th | 6 | Buster Warke | 1940 Studebaker | Connecting rod on 45th lap |

| 28th | 30 | Ottis Stine | 1939 Buick 40 | Connecting rod on 43rd lap |

| 29th | 12 | M.O. “Ebby” Ebersole | 1940 Ford | Hit guard rail, broke universal joint on 40th lap |

| 30th | 3 | E. Cooper | 1938 Buick | Connecting rod on 39th lap |

| 31st | 32 | Mace “Doc” McCarthy | 1939 Ford | Broken piston on 38th lap |

| 32nd | 20 | Tom Elmore | 1939 Ford | Overheating on 19th lap |

| 33rd | 61 | Neal Weymouth | 1940 Ford | Cracked cylinder head on 15th lap |

| 34th | 9 | Mark Light | 1939 Buick 60 | Hit fence on 1st lap |

| 35th | 46 | Adam “Doc” Ashbaugh | 1939 Buick 66C | 200 laps; disqualified from 3rd place, non-stock size tires |

| 36th | 34 | Metz Smith | 1940 Ford | 200 laps; disqualified from 4th place, non-stock motor |

There were 99 pit stops recorded.

Langhorne, 1941

The 1941 running of the 200-mile stock car race at Langhorne Speedway was held on 20 July. Rather than Hankinson Speedways being the promoter as in 1939 and 1940, the promoter for the 1941 race was Lucky Teter. The A.A.A. Contest Board issued Sanction No. 3869 for the race. Unfortunately, I have been unable to locate the Contest Board Bulletin that would cover this event.

As in previous years, the qualifying placed those qualifying earliest – and presumably fastest – on the inside row on the first day of qualifying and then filled the outside row on the second day. The number of starting positions for the 1941 event appears to have been 40, what it had been in 1939. Drivers mentioned include: Fred Winnai, Tommy Hinnershitz, Vic Naumann, and Bert Ross. Others mentioned include: Ace Levis, of Dorchester, Mass., who crashed on the final lap of one of the qualifying heats, with three others then piling into his car; and, Sam Moody, of Richmond, one of those involved in the Levis wreck who was hospitalized overnight as a result of injuries suffered during the wreck.29

The first eight positions, apparently those completing the full 200 miles, are all that seems to be readily available at the moment:30

1st Roy Hall (Atlanta, Ga.), No. 7, 1939 Ford coupe, 2 hr 55 min 25.46 sec

2nd Rodney Lummis (Warren, Pa.), 1941 Mercury sedan

3rd Walt Keiper (Trenton, N.J.), 1939 Ford coupe

4th Lloyd Seay (Atlanta, Ga.), 1939 Ford coupe

5th Tommy Mattson (Philadelphia, Pa.), 1940 Ford coupe

6th Harold Collier (Uniontown, Pa.), 1941 Oldsmobile sedan

7th John “Jack” O’Brien (Pittsburgh, Pa.), 1941 Buick convertible

8th Kenneth Applegate (Cranberry, N.J.), 1938 Ford coupe

According to Riggs, a review of the scoring cards resulted in Harold Brokhoff being placed fifth and Mattson then moved to the ninth position behind Applegate.

According to most accounts, there were about 42,000 spectators present for the race. Hall dominated the event, leading from the green flag to the checkered flag, but the wrecks seem to get almost as much coverage as the results. Most accounts mention up to seven wrecks of varying degrees of seriousness, involving those mentioned below, along with any of the injuries incurred:

• Jim Stonebreaker (Hyattsville, Md.): fractured jaw.

• Adam “Doc” Ashbaugh (Miamisburg, O.): fractured right arm as result of a three car wreck.

• Larry Bloomer (Collegeville, Pa.): back injuries as well as cuts to arms and legs when his LaSalle, no. 65, hit the railing at Puke Hollow and crashed.

• Dave Randolph (Long Island City, L.I., N.Y.), relief driver for Mac MacKenzie: escaped without injury when car rolled over and caught fire.

• Larry Darner (Zanesville, O.): his car, the no. 94 Cadillac, rolled over twice, but he walked away from the wreck with only bruises and cuts.

It is interesting to note that in 1939, the only stock car race sanctioned by the A.A.A. Contest Board was the Langhorne event. In 1940, in addition to Langhorne, the sanctions were issued for two additional stock car races. One was at Williams Grove Speedway, No. 3783, to R.E. Richwine for an event scheduled on 23 June and the other No. 3782, for a road race promoted by the Chamber of Commerce of Grand Junction, Colorado, to be held on 4 July.

In 1941, the A.A.A. Contest Board issued five sanctions for stock car races: the Langhorne event won by Roy Hall, No. 3869; No. 3874, issued to R.E. Richwine for an event at Williams Grove Speedway on 10 August; No. 3891, to Funk Speedways for an event to be held at Fort Wayne, Indiana, on 12 October; No. 3903, to C.B. Dowdy and C.O. Long for an event to be held on 4 July in Richmond at the Virginia State Fair Grounds; and, No. 3914, to Ronald C. Smith for an event to be held on 12 October at the Trenton Inter-State Fair Grounds.

The Williams Grove event featured an 80 lap final as the main event of race meeting, which was won by Walt Keiper of Trenton, followed by Jack O’Brien of Pittsburgh, and Bill France of Daytona Beach.31

Beyond 1941

The Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (Volume XIV, Special Bulletin) of 10 December 1940, had this addressing dirt track racing during the 1941 season:

Revision of Displacement Limits for Dirt Track Racing

Effective and commencing January 1, 1941, all non-championship dirt track or speedway races (Both Class “A” and Class “B”) conducted under A.A.A. sanction and rules shall be restricted to cars with non-supercharged engines of not more than 205 cubic inches of piston displacement, and supercharged engines of not more than 137 cubic inches.