1949 Brazilian Temporada

Brazil's forgotten racing days

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- June 12, 2024

Related articles

- 1934-'37 Rio GPs - Postcards from Gavea, by Mario Cesar de Freitas Levy/Leif Snellman/Antonio Carlos Barque de Lima

- 1950 Chilean GP - The first, the last and the only, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1966 Argentinian F3 Temporada - It's never too late to revive old passions, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1967 Argentinian F3 Temporada - Time to go south again!, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Argentinian F2 Temporada - The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1970-1975 Tasman Championship - Back to Pukehoke for a revival of F5000 Tasman days, by Gareth Evans

- 1971 Colombian F2 Temporada - When Formula cars roared in the Coffee Land, by Lorenzo Baer

Who?Rafael Gargiulino What?Ford V8 Adaptado Where?Belo Horizonte When?1949 Grande Prêmio da Cidade de Belo Horizonte |

|

Why?

When you ask someone about the association between Brazil and motor racing, most likely the first thing that will come to mind will be the names of the drivers who, from the 1970s onwards, began to write the most significant part of the history of motorsport in that country. Names like Fittipaldi, Pace, Piquet, Senna, Castroneves, and so many others, brought glory to the green and yellow flag, demonstrating the strength, over the decades, that the country had in generating talent on its tracks.

However, the history of these drivers was not built on the basis of spontaneous and random events which culminated in these successive generations. The maturation process of Brazilian drivers was the result of other pioneers who ended up being forgotten compared to the glories achieved by their compatriots in later decades. Drivers like 'Chico' Landi, Irineu Corrêa and Manuel de Teffé paved the way for what would become one of the most victorious countries in the history of F1, Indy and so many other prestigious international categories.

One of the most emblematic moments of Brazilian motorsport in the pre-war years was when Auto Union took one of its C-Types to the Gávea circuit, in 1937. Hans Stuck came second, behind the Italian Pintacuda in an Alfa Romeo.

(credits unknown, colourised by the author)

The 1930s and 40s were the first moments in which these, and some other pioneers, were able to compare strengths with their Latin American pears – and they soon demonstrated that in terms of quality the Tupiniquins were not far behind. It's no wonder that, at the beginning of the 1930s, Europeans were already intrigued by the buzz that was coming from Latin American motorsport and came here to investigate what the real situation was.

Brazil quickly became the main battleground for such disputes, with drivers like Hans Stuck, Carlo Pintacuda and Antonio Brivio defending the honours of the 'old continent' and placing hierarchical order in the situation. The Europeans proved to be almost unbeatable, largely due to the technological deficit that the Brazilians had to face – for example, when the above trio of drivers competed in the 1937 Gávea GP, with state-of-the-art Auto-Unions and Alfas, all the Brazilians could mount as opposition were a handful of outdated Alfa Romeos and Bugattis.

Even so, the Europeans soon recognised the tenacity of the Brazilian drivers who, even with inferior machines, fought for every metre and centimetre of ground on a track as technical and treacherous as the Gávea circuit (which would become the main circuit in South America in the 1930s).

Despite its dangers, the Gávea circuit was always well attended during its years of activity. In 1947, L. Villoresi, A. Varzi and Raphaël Béthenod were responsible for representing the European contingent in the race. (credits Brazilian National Archives)

The Second World War was an abrupt halt to this process of automotive cultural exchange, which was beginning to bear its first fruits. However, the end of Transatlantic relations did not mean the inevitable disappearance of high-level motorsport in Brazil. On the contrary, the country made an effort to maintain its calendar of events even during the conflict, forming a partnership with Argentina and Uruguay, two other strong exponents of American motorsport at the time. This 'automobile alliance' remained until 1943, when the effects of the war in Europe began to spill over the South American countries and finally forced the interruption of racing events in the three countries.

In 1946, however, the gears of motorsport started working again. The war was over, and with this new beginning, new airs surrounded racetracks all around the world. The old drivers of the pre-war generation were beginning to give way to new names, who would now carry on their shoulders the heavy burden of having to rebuild the world's motor racing structure. Even though the first steps of this reconstruction process were timid, Brazil had its share of contributions. For example, at the end of 1946, it had promoted two races of reasonable scope for GP cars (the II 'official' Grande Premio da Gávea and the I GP da Quinta da Boa Vista).

Brazilian motorsport lived not only through Interlagos and Gávea. Other tracks, such as the Circuito da Boa Vista, were frequent stops of national races for single-seaters. The photo above depics the 1950 race. (credits Correio da Manhã)

However, despite this process of restructuring Brazilian motorsport continuing at full steam in the following two years (1947 and 1948), one factor began to bother Brazilian race promoters. On the other side of the Rio de la Plata, an old ally began to steal the spotlight on the South American scene, promoting races with a level of quality never seen before in South America.

The culprit's name was Argentina, which had an extraordinary automobile boom in the years after World War II. In organisational, quantitative and qualitative terms, Argentinian races turned out to be much more attractive than those that, until then, existed in other parts of South America – especially the ones in Brazil. The Temporada, as the series of Formula Libre races held on Argentinian racetracks became known, turned into the crown jewel in the seas of the South Atlantic in the late 1940s.

This relegated Brazilian events to a secondary role, something that did not resonate well with the drivers and Brazilian public opinion itself. A resolute and speedy reply was necessary; and the solution found was to respond in the same kind and manner: and so it was, the idea of first Brazilian International Temporada was born.

The road to the Brazilian Temporada

The year 1949 began in high style in motorsports: a series of four races in Argentina would officially open the world motorsport calendar, with the good names of the new Argentine generation of drivers mixing with some of the main aces of European circuits. Juan Manuel Fangio and Óscar Galvez were the main representatives of the Argentines, while the Italians Alberto Ascari, Nino Farina and Luigi Villoresi, the British Reg Parnell and the Frenchman Jean-Pierre Wimille defended the teams from the old continent. The experienced Thai driver Birabongse Bhanubandh (commonly known as Prince Bira) was another who emigrated along with the European contingent towards the southern hemisphere.

Although it initially seemed that the championship would be dominated by the European giants (represented by Scuderia Ferrari and Scuderia Ambrosiana/Maserati) the reality was not that simple. The first race of the Argentine Temporada, the III Gran Premio del General Juan Perón, seemed to be confirmation of initial expectations, with Ascari and Villoresi dominating the first two positions on the podium.

However, the second race was a shock: the III Gran Premio Eva Duarte Perón was the stage for a spectacular performance by Oscar Gálvez, who, taking advantage of problems for the main European drivers, ensured that victory stayed in the hands of a home driver, for the first time in the year. A still unknown Juan Manuel Fangio finished second, making it an Argentine double on the podium.

Before the Italian drivers went to Brazil, they contested four legs of the Argentine Temporada, winning two of them. (credits Fondazione Pirelli)

In the next round, the III Copa Acción de San Lorenzo, the Europeans duly completed the payback with a 1-2-3 on the podium. Nino Farina and his Ferrari took victory in the race, followed by the Maseratis of Reg Parnell and Alberto Ascari, respectively. However, the pampas drivers were the ones who would have the last laugh in the 1949 Argentine Temporada, as in the II Gran Premio Internacional del General San Martín, held in Mar del Plata. Fangio and Galvéz once again took the podium; the first on the highest step, with Gálvez taking third (in between them was the Thai Bira).

However, the end of the Argentine Temporada was not the end of the adventures south of the equator for some of these drivers. During 1948, the Automóvel Club do Brasil (ACB) began to digest the fact that racing in Brazil was losing the so hard-fought prestige it had achieved in the previous decades. The fact is that sparse races like those promoted by the ACB did not have the same appeal as a 'mini championship' like those organized by the Automovil Club Argentino (ACA).

The success of the Temporada was due to its good schedule, which generally comprised four solid races spread over one month. This simple arrangement became itself an attraction for the big European teams, which could dilute the transportation and maintenance costs of all material from Europe to South America over the course of four events, in addition to the good prizes offered by those events, which were good lures for the top racing drivers. This was much more logical compared to the Brazilian scheme, which invested in only one or two attractive events throughout the year.

After failing to achieve a single victory in the Argentine Temporada, Luigi Villoresi was eager for a victory on Brazilian soil. (credits Fondazione Pirelli, colourised by the author)

Therefore, the ACB began designing the project for its own Temporada, following the templates built by the ACA. For this purpose, the Brazilian body created a subdivision called COTI (in English, the International Temporada Organizing Committee) which would be responsible for all logistical issues related to the event; at the same time, the ACB would only sanction the events that would make up the championship. Speaking specifically about these, the possibility of organising four races was immediately ruled out, mainly due to financial and contractual problems for the drivers.

Because of this, the Brazilian International Temporada would only have three legs, with the first two events being held in the city of São Paulo, and the conclusion taking place in the federal capital, Rio de Janeiro. Race number 1 remained a mystery until the beginning of 1949, when it was revealed that a street circuit would be established in the Pacaembu neighborhood, one of the oldest and most traditional areas of the city of São Paulo. The venue for race number 2, however, was no surprise, as it would use the facilities of the Interlagos circuit, which, at the time, had been operating for less than 10 years. The location for race number 3, in Rio de Janeiro, could be none other than the Gávea circuit, which continued to be the mecca of Brazilian motorsport.

A wise choice by the ACB was not to create any scheduling conflicts with the Argentine Temporada, hence the choice of the month of March to promote and host the Brazilian races. It was expected that with this short break, many of the European drivers, instead of returning directly to their places of origin, would make a short stopover in the tupiniquim country, adding truly international tones to the Brazilian event as well. It's no wonder that when the ACB's proposal became official, drivers like Farina, Parnell and Villoresi gave a positive nod to this new championship.

This succession between the championships held in Argentina and Brazil created an error that persists till this day. Many researches indicate that these two events constituted, in reality, just one huge event, which became known simply as the '1949 International Temporada'. However, this was not reality, since the Argentine Temporada and the Brazilian Temporada (at least in 1949) were two distinct contests, with each one being promoted by their respective national automobile organisations. The core of the confusion is due to the 'gentleman's agreement' that occurred between the two institutions to avoid a conflict of interests, with the ACB agreeing to hold its event only after the Argentine Temporada had unfolded. It didn't help either that the fact that both the Brazilian and Argentine press called their home championships 'International Temporadas', causing much confusion later in defining what really happened in 1949.

Race 1: I Prêmio Circuito do Pacaembu

The opening round of the championship was originally scheduled to take place on March 6th, that is, one week after the last race held on Argentine soil. However, the organizers of the ACB did not consider the logistical problems that existed, especially due to the fact that the cars that competed in Argentina had to pass through customs in two countries in the process. Observing that the international drivers would have difficulties in arriving on time to compete in the race, the ACB commissariat decided to postpone the event until the 13th, thus giving the minimum amount of time for the bureaucracy between teams and governments to be resolved.

In the end, the postponement would be of no use, as a set of factors prevented foreign drivers from competing in the opening race of the championship: the cars were still being transferred, with the international teams still assembling their temporary bases in São Paulo. The decision of the ACB of prohibiting practice on the track before the day of the race also hindered plans of those interested in participating in the event (the ACB, backed by São Paulo´s city council, alleged at the time that it was impossible to close urban roads solely for the purposes of practice and track reconnaissance).

Therefore, all the drivers went to the Pacaembu circuit in the dark – something that did not please the European drivers at all. The first to demonstrate true dissatisfaction with the ACB's methods, which were not remotely similar to the good standards outlined by the ACA, were Reg Parnell and Prince Bira. Both were scheduled to participate in the Brazilian Temporada as two of the main foreign attractions but seeing the disorganisation of the Brazilian commissioners both withdrew their entries and decided to return directly to Europe after the end of the Argentine Temporada.

This largely crippled the European contingent that would participate in the sequence of races. Only Luigi Villoresi, Nino Farina and Alberto Ascari kept their word with the Automóvel Club do Brasil, stating their desire to compete in the two other remaining races of the Brazilian Temporada. The official presentation of the Italian trio to the public would only take place on race day – which meant, to a certain extent, that only Brazilian drivers would compete on the Pacaembu Circuit.

The main name in the dispute would be of Francisco Sacco Landi, popularly known as 'Chico' Landi. Born in São Paulo itself, Landi had already become a nationwide figure by the late forties. Having started his career in 1933, the driver achieved good results in smaller races in Brazil, until he took his first major victory in the 1941 edition of the Gávea GP (in a race that no longer had European drivers).

In the post-war period, the driver's performance improved exponentially, being one of the few South American drivers who managed to compete in the Argentine Temporada on equal terms with his counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic. And any remaining doubts that still existed about Landi's talent were dispelled when the driver won the II Gran Premio di Bari (1948), facing strong opposition from drivers such as Varzi, Bonetto and other experienced Italian drivers.

Returning to his homeland after his victorious adventure in Europe, Landi had practically become a national hero, as his victory in Bari had given Brazil its first recognised victory in GPs outside its national boundaries. But despite this achievement Landi did not lose his focus – and soon he was once again a figure always present on the grids of Brazilian races. For the 1949 events in South America, Landi would drive a Maserati 4CL equipped with a 1.5-litre engine.

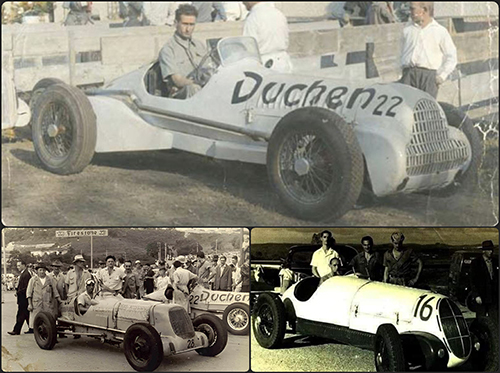

Photos of some of the characters of the Temporada: (top) Luiz Valente, Duchen Especial; (bottom left) Arlindo Aguiar, Ford V8-Adaptado; (bottom right) Jaime Neves, Alfa Romeo 6C 2300cc (switched to a 308 at the beginning of 1949).

Another well-known name in Brazilian motorsport at the time who would also race through the streets of São Paulo was Arlindo Aguiar. Since 1947, the driver was always present in Adaptados car races (which were street cars stripped of all weight and extremely modified) and GPs, achieving decent results in both categories – especially in the races held on the Interlagos circuit. For the race at Pacaembu, the driver would drive a Ford V-8 Adaptado, with a 3280cc engine.

Pointed out by part of the press as the possible surprise for the Brazilian Temporada, Francisco Marques had also prepared himself for the sequence of events that would unfold on March 13th. The half Portuguese, half Brazilian driver would drive a second-hand Maserati 4CL, a great vehicle for the conditions imposed by most Brazilian circuits at the time – very winding tracks, adapted to cars with smaller displacement engines but with greater torque.

In addition to these three, six other drivers signed up for the Grand Prix category in the Pacaembu race: Jaime Neves would be equipped with a 3000cc Alfa Romeo, Moacir Carlos Leite with a Maserati 6CM, Antonio Parra would drive a 2900cc Alfa Romeo Type B, Amaral Junior would enter another Ford V-8 Adaptado on the grid, Enrique Casini contributed to the numbers with another Alfa Romeo, the 'Casini' 8CM-308, while Francisco Credentino would drive a 3-litre supercharged Alfa-Romeo 8CM-308.

Despite major differences in engine capacity, the organisation hoped that the Pacaembu circuit itself would be a leveler for the race, providing a balance between points of greater speed (where Alfas with larger displacement would have an advantage) with more 'winding parts' where the more manoeuvreable Maseratis were faster. The route, 3100 metres long, crossed the streets around the famous Pacaembu stadium, which received its name due to the neighborhood in which it was built.

The stadium is still located today in a depression in the ground, surrounded by two adjacent hills. This topography had been exploited to the maximum by the organisers of the Prêmio Pacaembu: the finish/start straight of the circuit was in Paulo Passaláquia Street, which after a few metres turned into an ascent on the west side of the stadium. After bypassing the southern part of the sports complex, the drivers went through part of the residential neighbourhood of Pacaembu, before entering Itápolis Street. An abrupt turn to the right onto Armando Penteado Street was followed by another sharp curve, this time to the left, onto Itatiara Street. Thus began the descent along the east side of the stadium, ending around Charles Miller Square and returning to Passaláquia Street.

Due to the high accumulated amplitude and high degree of difficulty of the track, the ACB began reviewing its regulations for the race and the day before the official event decided to ban the participation of any new drivers in the GP race. In this way, the final number of drivers who would compete in the main race of the Prêmio Pacaembu was reduced to six – with Arlindo Aguiar, Amaral Junior and Henrique Casini being cut due to the new ACB guidelines.

However, there was a catch: in another change promoted by the organisation, it had defined that the two best classified in the Adaptados class (one of the support events of the race weekend) would also be awarded places to compete in the final race, elevating the final entry list for the Grand Prix event to eight cars. Because of this loophole, both Aguiar and Junior still had a chance of competing in the main Pacaembu race, as long as they took first and second positions in the Adaptados category event.

The warm-up of the Temporada took place on the Pacaembu street circuit. Despite already being present in Brazil, the Italian squad had to settle for watching the race from the circuit's grandstand. (credits unknown)

Race day had finally arrived but with it, torrential rain hit São Paulo. The intensity of the phenomenon was so great that the qualifying sessions scheduled to take place in the morning were canceled, with the drivers' starting positions being decided by draw. The result was: 1st row, 'Chico' Landi (#2), Carlos Leite (#4) and Jaime Neves (#6); 2nd row, Francisco Marques (#8) and Francisco Credentino (#12); 3rd row, Antonio Parra (#14) and the two drivers that would come out of the Adaptados race.

It was only shortly after 2pm that activities really started on the Pacaembu circuit, with a race for touring and sports cars opening the schedule. Afterwards, the Joaquim Buller Souto Trophy took place, the event for the Adaptados cars, and that would also give the final numbers for the GP race grid. Amaral Jr and Arlindo Aguiar monopolised the race, winning invitations to the final race without any difficulty. The end of the day was approaching on the horizon, when the eight drivers lined up for the race that would define the winner of the Coronel Nelson de Aquino Trophy (official name of the race for the GP cars in the I Premio Circuito do Pacaembu). Before the flag was dropped, Farina, Ascari and Villoresi were finally introduced to the crowd who were looking forward to seeing the Italians in action at the Interlagos GP, which promised to shake the paulista capital the following weekend.

End of the ceremony and authorisation to start was given. The one who took the lead was 'Chico' Landi, leading the field in the first of the 20 valid laps for the race. Behind him was Francisco Marques and his Maserati, who after an excellent start was already in full pursuit of the race leader. Jaime Neves remained in third, while Carlos Leite had dropped to fourth place.

Landi and Marques, from the second lap onwards, would engage in a personal clash, with the personal skills proving to be the difference between the two – as both were equipped with the same model of car (Maserati 4CLs). Further back, Francisco Credentino had managed to climb to fourth place; but this spot would not remain in his hands for long, because on the fourth lap the Alfa's differential broke, forcing the driver to abandon the race.

Soon, the field was pulverised into small skirmishes, Landi and Marques at the front. Neves and Leite were already well behind, further away were Parra, Aguiar and Júnior. In the middle group, Jaime Neves proved that he had a superior car to his opponent and despite some small efforts by Moacir Carlos Leite he achieved nothing. Apart from this brief harassment, Neves had a comfortable run in third place.

The same cannot be said for the drivers who were leading the race, with Marques becoming a menace in Landi's rearview mirror. The Luso-Brazilian waited until lap 6 when he finally unleashed his attack. The overtake was a success, with the roles of the hunt and hunter now reversed in the race. 'Chico' Landi, with his vast experience on the track, would not be put off by his opponent's daring manoeuvre and quickly sought to show off his response. On lap 7, the positions had alternated once again, with Landi resuming the first position and Marques having to settle for second place.

And with this pace, the race developed until the final moments, with the duo separated by just a few metres – the crowd went wild with the display of skill that both drivers promoted, with a clean and frank duel between both parties. But in the end, it was veteran Landi who prevailed, completing the 20 laps of the race with a total time of 41.13. In second place and just a tenth of a second shy was Francisco Marques, who had narrowly missed out on beating favourite 'Chico'. Completing the podium with a time of 42.39 was Jaime Neves and his 3000cc Alfa Romeo.

Therefore, the I Prêmio Circuito do Pacaembu, which was originally scheduled to be the big official debut of the Brazilian Temporada, ended up becoming just a prologue to the championship itself. However, the next race in Interlagos was already on the minds of all the drivers as soon as the chequered flag was dropped at the Pacaembu circuit. Finally, the moment of truth had arrived in the Brazilian Temporada.

Race 2: IV Grande Prêmio de Interlagos

Inaugurated in 1940, the Interlagos track was one of the first venues solely dedicated to the practice of motorsport in South America. Despite this interesting fact, until the beginning of the 1950s, the track was practically unknown to most international drivers, with only a handful Italians like Varzi, Pitacuda and Villoresi visiting the place over the years. Two main factors contributed to Interlagos not being so popular in its early years with foreign drivers.

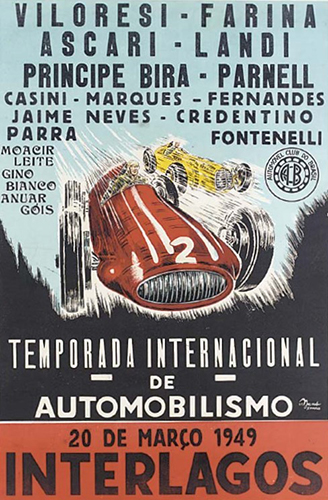

The 1949 Interlagos poster.

The first was a question of timing: when the track was completed, at the end of 1939, the Second World War was already underway, something that prevented any European Atlantic 'expedition' – thus, drivers from the old continent found themselves deprived of experiencing the new location until the conflict was concluded. And when the war ended, the second factor emerged: the Gávea circuit had once again become the mainstream attraction, due to the glamour and tradition of the carioca circuit, throwing the races in São Paulo into the shadows once again (at least, on an international level).

So, the 1949 Temporada was the chance that the administrators of the São Paulo circuit were waiting for. It was time to prove that Interlagos could offer a much more suitable place to host international events than the old-fashioned and dangerous Gávea circuit, with a modern infrastructure adapted to host the major events that, it was hoped, would one day take place on the site.

To ensure that everything ran as smoothly as possible, great efforts were made to elevate the circuit to a high standard, which would positively impress foreign guests. Much of the track had been resurfaced, trying to minimise vibrations and unnecessary wear on cars; the track's main grandstand had been expanded, considerably increasing the venue's capacity and comfort to the crowd; and an effective safety scheme would be put in practice, for the duration of the event.

Most of the drivers who competed in the race at Pacaembu, the previous weekend, were also present at the Interlagos autodrome. 'Chico' Landi and Francisco Marques intended to hold a second round of their duel, which saw the experienced Landi win in the first clash between the two. However, there was a notable difference between the situations in the Pacaembu and Interlagos.

Marques would continue to drive his 1500cc Maserati 4CL; however, Landi would drive an Alfa Romeo 308. This car had originally belonged to Achille Varzi, who later sold the machine directly to Landi. After using the 308 for a few years, Landi resold the vehicle to Enrique Casini in the mid of 1948. The carioca driver had made certain modifications to the vehicle, which was now almost a hybrid of original Italian parts with others produced locally in Brazil. However, one thing remained the same: the car was still equipped with its original monstrous 3000cc Alfa Romeo engine – and that was why Landi wanted to drive this car so much at Interlagos. Therefore, Landi and Casini made a verbal agreement before the IV GP of Interlagos: it would be agreed that Casini's car would be transferred from Rio to São Paulo the day before the race, while Landi's car would fly in the opposite direction, being handed over to the care of Casini himself.

Landi was extremely happy with the agreement, as he knew that only raw power could balance the scales against the most modern European machines: “We will be fighting and I hope that with the Alfa, I can match the famous Italian drivers. I believe in a broad success of the race, and I believe that the spectacle for the public will be wonderful”, he stated, in an interview for the newspaper Correio Paulistano, in March 1949.

In addition to those mentioned above, Moacir Carlos Leite, Jaime Neves, Francisco Credentino and Antonio Parra were the other drivers who did both legs (Pacaembu-Interlagos). These drivers were joined by five other Brazilian drivers, in addition to the three Italian stars: Giuseppe 'Nino' Farina, Luigi Villoresi and Alberto Ascari.

Before talking about these, it is worth quickly mentioning the Brazilian drivers who would make their debuts in the Temporada: one of them was Luigi Emilio Rodolfo Bertetti, known simply as 'Gino Bianco', who would become famous for his co-participation (along with Landi and the Uruguayan Eitel Cantoni) in the process of structuring Escuderia Bandeirantes, the first Brazilian Formula team to compete in a race in Europe, in the early 1950s.

But before his adventure as a team leader, the businessman had a modest life as a driver in Brazilian national races, especially in smaller events in the country, driving, on most occasions, a Maserati 6CM voiturette. However, for the Interlagos race, the driver had managed to make an agreement with his friend Landi, causing him to rent out to Bianco, just for this race, a 3000cc Maserati (to be precise, the 8CM with the chassis number 3007).

Another driver who deserves his due credit was Antônio Fernandes da Silva, an experienced driver in small events within Brazilian borders. Despite having created roots in the tupiniquim lands, Fernandes was of Portuguese origin and would run for the Portuguese flag in the race. One factor that made the driver decide to do so was the help from the huge Portuguese colony based in Rio de Janeiro, which made a crowdfunding campaign for him to buy a 1500cc Maserati 4CL.

In addition to these, the other Brazilian drivers present on the entry list were Osmar F. Lage (Maserati 4CM 1500cc), Annuar de Goes Daquer (Maserati 6CM 1500cc), Aloysio Fontenelle (Alfa-Romeo 8C Monza 2300cc), Rodrigo Valentim de Miranda (Maserati A6GCS 2000cc), Rubens Abrunhosa (Alfa-Studebaker) and Hans Ravache (Alfa-Romeo 8C Monza 2300cc).

However, it was undeniable that all the attention was focused on the drivers from the tarantella land: the Scuderia Ambrosiana had finally received its cars on Monday, the 14th. Both 'Gigi' Villoresi and Ascari were eager to test their vehicles on the fast circuit of Interlagos, with its more than 8 km of straits and swift bends. Not only did the drivers have expectations, but also the team itself.

The Interlagos circuit presented very different characteristics from those that the Scuderia Ambrosiana had seen until then in 1949. Most of the races in Argentina took place on street tracks, with little or no amplitude. Interlagos, on the other hand, was a track with long straights and high-speed curves, with ups and downs. It would be great for the team to know how the car would behave on this type of circuit, considering European races with the same characteristics as the Brazilian circuit.

Both drivers would have at their disposal 1500cc Maserati 4CLT cars. Ascari would drive the car with chassis #1593 (the same one that the driver used to achieve his victory in the Gran Premio del General Juan Perón, just over a month earlier), and Villoresi would have the chassis #1594. As stated earlier, those cars were Temporada veterans, with both machines being at the peak of their performance curve.

On the other side of the pits, Scudeira Ferrari was also preparing for the GP in São Paulo. Nino Farina would be the team's lone representative in Brazilian territory, driving the 2000cc Ferrari F1 125C, with chassis number #04C. The driver hoped to be able to repeat his best performance in South America until then, achieved in the III Copa Acción de San Lorenzo, when Farina snatched his maiden victory in the 1949 Argentine Temporada.

On Thursday (17) the cars entered the track for the first time, with the drivers being given a generous free practice session before the qualifying races, which would only take place on Saturday. It was the ideal time for the teams to make the final adjustments – and, for the Brazilian drivers, this was a good time to see at what level their European rivals' machines were at.

And they certainly weren't very optimistic about what they saw. The Italian trio, despite starting slowly, quickly set a pace that was unattainable for the Brazilian drivers. Nino Farina's Ferrari was the one that offered the most memorable spectacle, circulating swiftly around the track. The driver had clocked 3m59s on his first timed lap; a time that was gradually reduced over the next few laps (initially going to 3m51, then 3m50 and reaching 3m49s). At the end of the session, Farina managed to reduce his mark even further, achieving the fastest time of the day in Interlagos, with 3.48.

However, the Maseratis of Villoresi and Ascari were also not far behind the pace of the Maranello car. 'Gigi' had managed to set a mark of 3.55, while Ascari was a second behind, with 3.56.1. This basically demonstrated the dominance of foreigners who despite being few in numbers monopolised the top positions. In this case, it can be seen that the fastest Brazilian driver of the day was Landi, who clocked a 4-minute lap, which took him to fourth position in the day's standings.

Even so, some other drivers also tried the track that 17th March: Moacir Carlos Leite, Francisco Credentino, Osmar Lage, Fernades da Silva, Jaime Neves, Francisco Marques and Antonio Parra – all of them took their laps around the track, with only Carlos Leite (4.31) and Francisco Credentino (also 4.31) making 'fast' laps around the track.

Friday would be a day off for drivers and teams, with official activities only resuming on Saturday, the 19th. On the eve of the official day for the Grand Prix car race, would be held, in addition to the official qualifying session for the main event, two other multi-class races, which would open the official race schedule of the IV GP of Interlagos. The first, open to Touring and Força Livre cars, had as the overall winner Aristides Bertual, in a 3.5l V6 Chevrolet Força Livre. The second race, open to super-sport and adapted cars, ended with the victory of Raphael Gargiulino, in a 3,280cc Ford-V8 Adaptado.

As these trials unfolded, all the weekend's top stars could do was wait. Villoresi, Ascari, Farina, Landi and all the remaining competitors in the GP category were already impatient, about the time to finally be able to get on the track. In addition to impatience, concern was another adjective common to all drivers present in the pits.

This happened because as the hours went by in the capital of São Paulo, the weather above the racetrack became increasingly hostile. As was already known to all Brazilians, it is common between the months of December and March for heavy rains to follow a day of intense heat, as was the case on that 19th. At the end of the second support event of the day, dark clouds were already appearing on the Interlagos horizon, foreshadowing difficulties for the classification races.

Then, a mad dash began to develop in the pits – drivers and teams moved all the necessary equipment to the designated areas, with the cars being quickly pushed into their pit zones. When the track was opened, Farina and Ascari were the fastest to enter it. They were followed by Landi, J. Neves and Franciso Marques, who were also quick to recognise that the track conditions were deteriorating fast.

Due to the fast reaction of these drivers, only they managed to set times before a downpour fell on the Interlagos circuit, interrupting the classification session indefinitely. Nino Farina was once again the fastest, despite setting a time worse than that achieved on Thursday: 3.53.2 gave him pole position for Sunday's official race.

Next to the Ferrari on the starting grid would be Ascari's Maserati, which had managed to set a time of 3.57.4. Landi and Neves closed the front row, with times close to 4.06. Other drivers, such as Villoresi and Credentino, desperately tried to set times before the rain hit the circuit; but their attempts were futile. These drivers now only had the opportunity to do a recovery race, hoping that some disadvantageous positions would not hinder their ambitions too much. And when it became clear that the rain would not stop until the evening, all teams decided to retire, only having in mind now the planning for the next day's race.

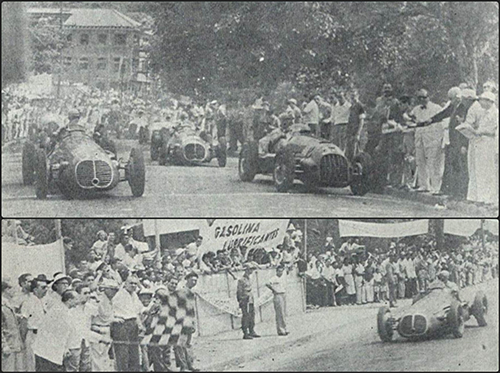

A rare photo of the start of the IV Grande Prêmio de Interlagos. One can see Landi (car #2) and Farina (#36) jumping ahead of Ascari (#22). (credits unknown)

Sunday dawned with a clearer sky over the Interlagos circuit. Preparations for the race began early in the morning, with the first striking news of the day arriving around the same time. The Alfa 308 that 'Chico' Landi was scheduled to drive in the race was declared unavailable for the driver at the last moment.

This happened because Henrique Casini, the current owner of the car, unilaterally cancelled his agreement the day before, giving as his reason that he wanted to preserve his machine for the Gávea GP, the next stage of the 1949 Temporada and in which he intended to participate. This was an unexpected blow to Landi's ambition, due to the sudden change in Casini's will at such short notice.

Not only was Landi shocked by Casini's attitude. The news was not well received by the public and the Brazilian sports press, as the Landi-Alfa 308 combination was, apparently, the only one that could pose a threat to the Villoresi-Farina-Ascari trio. The public's revolt was so great that even the Automóvel Club do Brasil was involved in the conversation, with a unanimous request for Casini to be punished by the ACB as soon as possible.

However, there was nothing that the ACB could do with regards to the driver's attitude, given that the agreement had been verbal, with no evidence of this other than some witnesses who saw the handshake between Casini and Landi a few days earlier. Therefore, Landi was forced to drive the Maserati 4CL that he had used in practice, a car certainly inferior to those of the European drivers.

After overcoming this early drama, the racetrack was ready to welcome the crowd who quickly gathered in the various accessible parts of the track. More than 80,000 people were present when the cars finally began to be pushed into their starting positions.

The grid was composed as follows: first row – N. Farina, A. Ascari, C. Landi and J. Neves; second row – F. Marques, F. Credentino and L. Villoresi; third row – H. Ravache, A. Parra, M. Leite and A.F. da Silva; fourth row – R. Valentim and O. Lage. Gino Bianco, Aloysio Fontenelle, Annuar de Goes and Rubens Abrunhosa ended up not attending the race in S. Paulo, deciding to focus their efforts on the Gávea race. 15 laps would be held on the Interlagos, with the event expected to last a little over 1 hour.

At 3:45 pm the flag was given, and ten cars went down the main straight of the Interlagos circuit. The exception was Hans Ravache's car, which had engine problems at the start and left the starting line a few seconds behind. On the other hand, further ahead, Nino Farina tried to secure the lead, followed by Landi, who had an almost perfect reaction time. Ascari lost a few precious seconds at the start, dropping to fourth position. Villoresi had some better luck, managing to steal third place from his teammate.

The duel between the drivers was intense in the first kilometres of the race, with Landi and Farina attracting all eyes. And the Brazilian public went wild when Landi managed to overtake the Italian, in the old turn number 3 of the Interlagos circuit. This was already a remarkable feat, given that Landi's Maserati, worn out after a few years continuous use, was a clearly inferior car to Nino's Ferrari 125C.

At the end of the first lap, Landi was leading, followed by Farina, Ascari and Villoresi. A second group, composed of F. Marques, F. Credentino and A. Fernandes followed a few seconds behind. Already far behind were A. Parra, M. Leite, R. Valentim and O. Lage.

Second lap around the track, and Landi continued to lead the field. However, further back, Villoresi had managed to overtake Farina and Ascari, threatening the Brazilian's lead. And, in the trickiest part of the circuit, Villoresi took the lead, relegating Landi to second place. At this point, technological superiority began to become apparent, as Landi was unable to respond to attacks from his rivals.

Farina was another to seize the opportunity and manage to overtake the Brazilian on the next lap. On the fourth lap, Villoresi and Farina had already distanced themselves, leaving the fight for third place between Landi and Ascari. On the fifth lap, the last major change in this first part of the race, when Farina, taking advantage of a gross error by Villoresi, overtook his compatriot to take the lead of the race. From then on, a brief moment of stability developed, with only a few slower cars withdrawing from the race.

However, the tranquility disappeared on lap 8. 'Chico' Landi was forced to retire from the race after a systematic failure of the bearings and connecting rods of his Maserati, due to the stress that the driver had imposed on the vehicle during his battles against Ascari, Villoresi and Farina. There was no repair that could be done, and the driver simply became a spectator of the race... until lap 11!

Francisco Credentino, a longtime friend of Landi, during the pitstop on this lap, decided to give up of his chances in the race and let Landi take over the controls of the Alfa Romeo #12. At that point, neither driver had any greater ambitions in the race: Credentino was running in sixth position before the pitstop and the driver change, while Landi was already three laps behind the leaders. But that didn't stop an ovation from the crowd who were happy to see Landi back in the race.

At this point, an intense relay in the lead was taking place between the three Italian drivers. Leader Farina entered the pits on lap 9 for a tyre change – the pitstop took longer than expected and the driver only returned to the track in fifth position. The one who ephemerally took the lead again was Villoresi, who stayed in this position for just one lap. Therefore, on lap 11, it was Ascari's turn to lead the table, something the Italian did for the next two laps.

On lap 13, Ascari began to experience mechanical problems and without delay his car headed towards the pits. Villoresi resumed in the lead, followed by the Portuguese driver Antônio Fernandes and the Luso-Brazilian Francisco Marques. Nino Farina was in full pursuit of the two, until lap 15 when at Curva do Lago the Ferrari's right rear tyre came loose, with the car only stopping in a ditch on the outside part of the curve.

Despite the grid being almost decimated, there was still some action for the crowd on the Interlagos circuit. Fernandes and Marques battled intensely for second position in the remaining laps of the race, with seconds separating the two drivers. Marques set up his ambush and on lap 19 launched his final attack – which ended up being extremely successful.

Luigi Villoresi, who was already well ahead, hadn't even noticed the battle, crossing the finish line first, with a total time of 1.20.30.9, more than two minutes ahead of second place Francisco Marques. Antônio Fernandes da Silva closed the podium, being at the chequered flag tenths behind Marques. The other classified drivers in the race were Alberto Ascari (fourth, with 19 laps) and Chico Landi (fifth, with 19 laps – the number of laps were credited to the car, not the driver).

There wasn't much time for celebrations, given that within a week, the teams' entire infrastructure had to be transferred from Interlagos to the Circuito da Gávea. It was time for the third leg of the Temporada; it was time for the infamous 'Devil's Trampoline'.

Race 3: X Grande Prêmio da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, the world's renowned cidade maravilhosa. City known for its beautiful beaches, its famous Carnival and the smiles and joy of the public. But, until the end of the 40s, it was also known as the epicentre of Latin American motorsport, due to being the annual venue of the acclaimed and prestigious Grande Prêmio do Rio de Janeiro.

The 1949 Gávea poster.

Much of the race's fame was due to the circuit that hosted the event, known as Circuito da Gávea. Just over 11km long, the route began in the Gávea neighbourhood, on the Marquês de São Vicente street, from where the drivers headed towards the Leblon, along the Visconde de Albuquerque street. Soon after, the drivers entered the long loop, bypassing the Dois Irmãos Hill and the Vidigal community along the Niemeyer Avenue, until reaching the São Conrado neighborhood. At this point, the return to the starting point along Estrada da Gávea began, going up and down the mountains that today are the site of the Favela da Rocinha.

Due to the technical difficulty of the layout, the track gained two interesting nicknames: for European drivers, it was the 'Nürburgring of the southern hemisphere', due to the great amplitude of the layout, mixed with extremely fast sessions and others that were painfully slow. However, for Brazilian and Latin drivers, the track would forever be marked as the 'Trampolim do Diabo' (in English, the Devil's Trampoline), due to the countless terrible accidents that happened on the circuit during its years of activity.

Drivers like 'Nino' Crespi and Irineu Corrêa were some of the fatal victims of the track in the thirties, as well as some spectators, who lined up on the completely unprotected sides of the track. Even so, the Gávea Circuit continued to attract a good number of drivers, who wanted to test their skills on one of the most challenging circuits in the world.

Therefore, after the end of the race in Interlagos, it is not surprising that a migration of drivers took place between São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. 'Chico' Landi, Francisco Marques, Francisco Credentino and Antônio Fernandes, as well as the Italians Ascari, Villoresi and Farina, quickly packed their bags and headed towards the capital of Rio. And, since the time between the two legs was short, all possible means of transport were used by the drivers and teams: some dispatched material by air, others decided to use the land routes that connected both cities, while others opted for sea transport.

In the end, it didn't make much difference, as the track activities would only start on Friday – and, by then, all the cars were already assembled and ready for the challenge of the Gávea circuit. The total number of cars for the race reached 14, as, joining the contingent from São Paulo, were Henrique Casini (Alfa Romeo 8C-308 3000cc), Annuar de Goes Daquer (Maserati 6CM 1500cc), Aloysio Fontenelle (Alfa Romeo 8C Monza 2300cc), Carlos Barbosa (Alfa Romeo 8CM 3000cc), Domingos Lopes (Bugatti T51 2260cc), Rodrigo Valentim de Miranda (Alfa Romeo A6GCS 2000cc) and Nino Stefanini (Alfa Romeo 8C Monza 2300cc).

Most of these drivers took part in the first day of free practice, on Friday. Of the Italians, it was Villoresi who stood out – largely due to his previous knowledge of the track, as he had already competed in a race at the Gávea Circuit, in 1947 (which he came in second, losing to Landi). 'Gigi' Villoresi was aggressive with his machine, being the fastest of the day, with a time of 7.19.5.

Nino Farina tried to keep up with his compatriot, but he was always a few seconds short of the time set by 'Gigi'. Farina would end the day with a time of 7.25.2 – not bad for the driver's first experience on the fearsome circuit. Of the Brazilians, the highlight was Casini, who was the only driver who managed to sneak between the Italian aces on the first day of training. His time of 7.41.2 was just over 20 seconds faster than Ascari's best time of the day, with the second Scuderia Ambrosiana driver having to settle for fourth place.

Chico Landi goes down the Visconde de Albuquerque street during the 1947 edition of the Gávea GP.

(credits O Globo, colourised by the author)

Saturday, the 26th. The definitive classification sessions were scheduled for that day, which would only take place after a journey full of support events, mostly composed of motorcycle races. It was only at 3pm that the cars returned to being the main stars of the Rio circuit.

It was at that moment that the news of the first casualty on the grid was received. Francisco Credentino would not drive his Alfa Romeo 8C, leasing his car to 'Chico' Landi instead. Landi, until then, found himself in a limbo, due to having his registration guaranteed in the event's entry list, but not having a car to compete with (at the time the first training sessions started at the Gávea, Landi quickly realised that he wouldn't be able to fix in time the extensive damage that his Maserati had suffered on the Interlagos race). Due to Landi's high popularity with the crowd, Credentino helped his partner by renting his car to Landi during the duration of the X Grande Prêmio da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

To the happiness of the ACB organisers, Credentino's case was the exception, as no other withdrawal request reached the hands of the event promoters - although Francisco Marques threatened to do so, due to a sudden fever that the driver contracted after the São Paulo race. However, the driver's quick recovery allowed him to participate normally in Saturday's training in Gávea. Certainly, the loss of Marques for the race would have been bad for the event's image, even more so after the excellent duel that the driver had with Portuguese driver Antônio Fernandes in Interlagos. Great expectations had been created, predicting that Marques could be one of the outsiders to disturb the leaders once again in the race.

At 3pm sharp, the first cars entered the track. The engines roared as the cars passed along the Niemeyer Avenue, almost suspended over the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, weaving them through the dense forest in the Tijuca massif, until the challenging climb of the Alto da Boa Vista, almost 300 metres above sea level. Despite its danger, it was undeniable that the Gávea circuit was one of the most spectacular racetracks of its time, perfectly framing the natural and human-built beauties, which made up the scenery of Rio de Janeiro.

Luigi Villoresi didn't even seem like a foreigner, as he skillfully mastered the tricky track. Again, he was the fastest driver of the day, dropping his time to an impressive 7.02.9! Nino Farina was also quick on the track, managing to secure second place with a time of 7.23.1. Further back, Landi was the one who caused the big surprise of the day, beating Ascari for third place on the starting grid. The Brazilian, with a time of 7.35.4, was just six tenths ahead of Ascari, meaning that at least one driver wearing the green and yellow colours would start on the front row of the grid.

Much of this result was due more to Landi's experience at the Gávea Circuit than to the machine the driver had on his hands. Although the Alfa that the Brazilian driver was driving had a 3000cc engine (compared to Ascari's 1500cc engine), the Italian's car was much sleeker, something that made a huge difference in the most tortuous part of the carioca track (the climb of the Alto da Boa Vista and then the descent to the Hipódromo da Gávea). However, Landi had been driving in Gávea since 1934, having participated in almost 15 events there – something that certainly played in the Brazilian's favour and reduced the technological deficit between the Italians and Landi.

Among the others classified were: 5th, Henrique Casini (7.41.9); 6th, Francisco Marques (7.52.9); 7th, Aloysio Fontenelle (8.06.2); and 8th, Rodrigo Valentim de Miranda (8.22.4). The other five drivers who would take part in the race did not want to set times, wanting to preserve their machines as much as possible for the next day's race.

A Sunday with the look of Rio de Janeiro appeared the following day, with lots of sun and a crowd that filled the streets of the city's Zona Sul. The X Grande Prêmio da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro promised to be a great spectacle, with the clear objective of consolidating the capital of Rio as the mecca of Latin American motorsport.

To try to achieve the highest level of competitiveness possible, the race promoters, together with the ACB and the Temporada drivers' association, decided to reduce the valid laps for the GP from 20 to 15. This decision came from observations and suggestions from the three parties, who saw the infeasibility of a clear dispute during the original total duration of the race – largely due to mechanical problems, which would certainly take out a large part of the field before the 20 laps and which, consequently, would cause a lack of interest of the audience.

Another problematic point was that many of the teams were beginning to have difficulties in finding high-octane fuel in Rio de Janeiro, which generated the first signs of fuel rationing on the grid. Especially affected were the most modern cars of the group (the Maserati CLs, the Alfas 308 and the Ferrari), which were highly dependent on top-quality fuel to avoid melting their engines.

Therefore, the numbers closed at 15 laps and 13 cars. At am, all vehicles were already lined up in their starting positions, ready for the flag. The cars were separated into small groups, a few metres apart, to avoid accidents, like those that had occurred in some previous editions of the event. Villoresi, Farina, Landi and Ascari would start in the first group; in the second, there were F. Marques, H. Cassini and R. Valentim; behind, two other groups, containing the other drivers in the race.

Images of the X Grande Premio da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro: the start and the chequered flag. (credits ACB)

The start signal was given, and it was Ascari who jumped into the lead, followed by Farina and Landi. Villoresi was slow in his reaction time and was in fifth on the way up to the Oscar Niemeyer Avenue. Francisco Marques had stolen the position from the Italian driver at the start, significantly changing the face of the front group on the first lap. Further back, Casini had lost several positions, after a poor start, which had seen the driver fall from fifth to 12th on the grid.

End of the first lap, and Ascari seemed secure in his first position. This was not the case for his compatriot Farina, who found himself locked in a battle with Landi for second place. Watching the duel between the two drivers was Villoresi, who was on the lookout for any error on the part of one or the other driver. It was also at the beginning of the second lap that there was the first retirement of the race: R. Valentim de Miranda, who was in sixth position and behind 'Gigi' Villoresi and F. Marques, broke his gearbox, causing his Alfa A6GCS to lay ill on the side of the track.

However, it was only on the third lap that the first major change in the group of leaders occurred: Landi, in his intense pursuit of Farina, lost focus in one of the key parts of the track, close to the Jockey Club. Instead of the driver avoiding the tram tracks (a maneuver that all drivers did we running on the Gávea circuit), which ran parallel to the urban road, Landi went over them – and the result was a punctured crankcase, which, less than a lap later, would declare the end of the race for the Brazilian driver.

Landi's unlucky moment meant that in the top three positions were the three Italian drivers. Ascari was leading far in the distance, two minutes ahead of Farina and Villoresi, who now monopolised the fight for second position in the race. Nino had some margin over his rival, something that allowed him to hold second position until lap 7, when the drivers switched positions.

Luigi Villoresi now focused on reducing his advantage over Ascari, with each driver's ability to negotiate with the track being the big difference between victory or second place in the race. Villoresi had started well, grinding down 10 seconds per lap if compared to Ascari. However, despite the initiative, it seemed that nothing could take away from Ascari the victory in Rio de Janeiro – the driver had even managed to set the circuit's record lap under racing conditions, with 7.21.7. But in a race, a driver never depends only on himself to win, being also influenced by other external factors. And one of them decided to get in the way of Ascari, on the 9th lap.

While trying to overtake Domingos Lopes (who was at that point in seventh position) in the section between the Jockey Club and the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Ascari misjudged the move past the backmarker and ended up crashing with the rear of his opponent's vehicle. Freitas managed to control his car after the collision, stopping smoothly on the side of the track.

However, Ascari was not so lucky, as the Maserati was catapulted into the air, with the driver being ejected from the vehicle in the process. Despite the severity of the accident, Alberto Ascari was lucky, earning only a few bruises and two broken ribs as a result of the accident.

Villoresi, who had nothing to do with his compatriot's accident, took the lead, promoting Giuseppe Farina to second and Francisco Marques to third. As incredible as it may seem, 'Gigi' Villoresi, just a few laps before Ascari's accident, had suffered almost the same fate as his teammate; trying to overtake Casini, Villoresi lost control of the car and collided with the Brazilian driver.

Luckily, neither car nor driver were hurt by the accident, with Villoresi controlling his car masterfully after the collision. Only a small spin, which had costed him a few seconds, was the consequence of the contact with Casini. The driver's control in this incident was essential and certainly one of the key points that now contributed to give him the lead in the X Grande Prêmio da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

In the following six laps, there were no other major changes to the order, with all drivers satisfied with their track positions. Luigi Villoresi would be the first to cross the finish line after 15 laps, with a total time of 1.57.17.3, 42 seconds ahead of second place, Nino Farina. In third place, bringing happiness to both the Brazilian crowd and the Portuguese community in RJ, was Francisco Marques, more than four minutes behind the Italian leaders.

Thus, the 1949 Brazilian Temporada came to an end. Despite the broad dominance of foreign drivers in the two races that officially counted for the championship (Interlagos and Gávea), this in no way detracted from the performance of the Brazilian drivers, who, despite having clearly inferior machines, were able to offer some resistance – in particular, Chico Landi and Francisco Marques.

However, this was not yet the end of the Brazilian adventure in 1949. A final chapter, dedicated only to national drivers, deserves its due emphasis. The next great stop was another large Brazilian population centre: Belo Horizonte.

Race 4: I Grande Prêmio da Cidade de Belo Horizonte

Despite not being part of the official ACB Temporada, the 1949 Grande Prêmio da cidade de Belo Horizonte needs to be mentioned in this text due to several factors, which contributed significantly to this event becoming one of the most important and striking episodes of the Brazilian automobile calendar that year. The uniqueness of the race, coupled with its proposal and execution, would reverberate during the following years: the GP, which had been born with great expectations, would ultimately be the biggest fiasco in Brazilian motorsport in the 1940s.

After the 1949 Gávea GP, the Italian trio Ascari-Villoresi-Farina sailed for Europe again, leaving behind only the memories of their spectacular performances on the Brazilian circuits. It was now up to the tupiniquim drivers to once again brighten up the national motor races, filling the grids and providing the crowd with purely Brazilian entertainment, in shades of green and yellow.

Some small races took place between April and July, especially in the interior of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, states where the majority of Brazilian drivers lived. However, for August, the ACB had promised to hold another major event which, it was hoped, could rival the Interlagos and Gávea GPs in the coming years: it was the GP da Cidade de Belo Horizonte, in the state of Minas Gerais.

Despite having some tradition generating drivers for the national GP and touring categories, Minas Gerais had not hosted any relevant races in the Brazilian scene until that moment. Therefore, when the possibility of holding a race in the state began to be considered, featuring most of the big names in Brazilian motorsport, this proposal quickly gained strength, mainly due to the project's main interested parties.

Names like Juscelino Kubitschek (at the time the federal deputy of Minas Gerais, and who would become president of Brazil from 1956 to 1961) and Octacílio Negrão de Lima (mayor of Belo Horizonte in 1949), together with the Minas Gerais branch of the ACB, made an ostensible lobby campaign, so that Belo Horizonte would finally be granted the possibility of hosting a GP-style sanctioned race. In the end, the pressure exerted by these characters would be successful, as the national committee of the Automóvel Club do Brasil finally accepted the pleas of the mineiros.

The most interested person in the event ended up being Juscelino Kubitschek himself, who was a great enthusiast of the automobile industry and the American-style 'vehicle culture'. He envisioned that, through car racing and other automobile events, there was a great tool to spread this line of thought among the middle and lower strata of the Brazilian population, who were the biggest socio-economical groups of the Brazilian society in the late 40s - and who still had some difficulty in associating the vehicle as a necessary good in their day-to-day lives. Entertainment was the best way to spread an idea, and racing, with its popular appeal, was the way to achieve it.

The enthusiasm was so great that it was JK himself, with the support of Octacílio Negrão, who would suggest where the race should be held, covering a route of approximately 18km around the Pampulha Lagoon, one of the landmarks of the capital of Minas Gerais. Officially inaugurated in 1944, the complex encompasses a large artificial lagoon and a conceptual architectural complex, designed jointly by a world-renowned trio, composed of architect Oscar Niemeyer, landscaper Burle Max and painter Candido Portinari.

It was expected that the modernist vision of the place, harmonised with the surrounding nature, would become the ideal attraction for any large event that could be held in Belo Horizonte. And the drivers, intrigued by this race, could not resist the invitation to compete in the meeting, which was scheduled to take place on August 14th.

Names like 'Chico' Landi, Francisco Credentino, Francisco Marques and Henrique Casini were the main names on the list, joining 17 other drivers in the capital of Minas Gerais. However, when the drivers arrived at site, days prior to the race, they were scared by what they saw: the word 'security' was non-existent at the track, with little (if not, any) protection between the crowd and cars in the most dangerous parts of the circuit. The surface variation on the site was notable, with sections of gravel interspersed with others of cobblestones and paved with concrete. Landi, in an interview with the newspaper O Cruzeiro, in 1949, stated that “there is more danger in Pampulha than in Gávea” (which was a clear testament of how dangerous the track was).

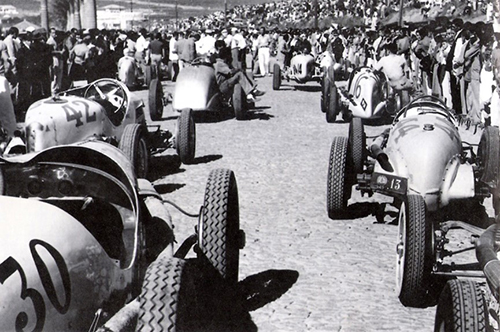

The cars are pushed to their starting positions in the Grande Prêmio da Cidade de Belo Horizonte. (credits unknown)

Even so, it was already too late to make any decision to boycott – and, like any driver in the 1950s, those registered in the race resigned themselves, getting into their cockpits and pushing forward, despite the adverse circumstances. Chico Landi, in his already rebuilt Maserati 4CL, and Portuguese Antônio Fernandes, were the fastest drivers in official practice, securing the first two positions on the starting grid. Fernandes would drive an Alfa Romeo 8C-308 in this race, the same car that Henrique Cassini had owned until then. After completing the season's Temporada, the Portuguese driver decided to buy the vehicle from the Brazilian, complementing the operations he already had with his own Maserati 4CL. However, as the transaction had not yet been completed by the time the race took place in Belo Horizonte, the drivers entered into an agreement that each would drive half of the race, with Fernandes doing the first stint.

Sunday the 14th, and 21 cars lined up on the starting grid for the race in Belo Horizonte. The drivers in the Grand Prix category were (in alphabetical order): Aloysio Fontenelle (Alfa Romeo 8C 2300cc); Annuar de Goes Daquer (Maserati 6CM 1500cc); Antonio Parra (Alfa Romeo Type B 2900cc); Aurélio Ferreira (Maserati 8C 3200cc); 'Chico' Landi (Maserati 4CL 1500cc); Domingos Lopes (Bugatti T51 2260cc); Francisco Marques (Maserati 4CL 1500cc); Gino Bianco (Maserati 6CM 1500cc); Jaime Neves (Alfa Romeo 8CM-308 3000cc); Nino Stefanini (Alfa Romeo 8C Monza 2300cc); Osmar Lage (Maserati 4CM 1500cc); in addition to the duo Antônio Fernandes and Henrique Cassini (Alfa Romeo 8CM-308 3000cc). Francisco Credentino (Alfa Romeo 8CM-308 3000cc) would not start.

Racing alongside the GP vehicles were the representatives of the Adaptados category: Amaral Junior (Ford V8 Adaptado 3,622cc); Charles Herbal (C.H. 'Hudson' Special 4250cc); Rafael Gargiulino (Ford V8 Adaptado 3,622cc); Marco Tassini (Alfa Romeo 8C Adaptado 2300cc); Otacílio Rocha (Hudson Adaptado 4293cc); Pascoalino Buonacorsa (Ford V8 Adaptado 3622cc); Rubens Abrunhosa (Alfa-Studebacker 1500cc); Walter Tassini (FIAT 1500 1493cc); and a duo composed of Gilberto Machado and Rafael Santos Rocha (R.S.R. – the engine of this car was probably a tuned version of a Plymouth, Ford or Studebacker).

12 laps would be the total distance to be raced on the 18km circuit and at 2:30pm, the moment of truth had arrived – the one that would define whether the Pampulha circuit could be elevated to the highest level of Brazilian motorsport, standing alongside Gávea and Interlagos as a regular stop on the national motorsport calendar. Flag lowered and it was Antônio Fernandes who shot ahead, followed closely by 'Chico' Landi.

However, the Portuguese's lead was shortlived, as before the Yacht Club turn (the first control point, located just over 500 metres after the start), Landi had regained the lead. Francisco Marques was in third place, observing the duel for the lead from a privileged position on the track. These positions remained until the end of the first lap, with the trio already significantly distancing themselves from the rest of the field.

The false sense of security generated by the clean start in which none of the competitors had any problems or accidents, was a relief for the race organisers. However, this feeling did not last very long, because on the second lap was the moment when the obvious problems of the Pampulha circuit began to become evident, even to the most skeptical.

In his duel for first place with Landi, Antônio Fernandes pushed his Alfa Romeo 308 to the limit, demanding the maximum from the machine. In the curves, the driver braked as 'inside' as possible, trying to stay close to the Brazilian driver's sleeker Maserati 4CL. However, this strategy took its toll in the middle of the second lap, when the Portuguese driver lost control of his car in one of those corners.

According to subsequent investigations, Antônio Fernades was unable to correctly select one of the gears when he was slowing down to make the turn, the car spun and hit the side of one of the bridges that were part of the circuit (which cross over the southern tributaries of the Pampulha lagoon). The crash was so violent that the engine and rear part of the car were simply torn off the chassis.

What was left of the car burst in flames, as gasoline poured down from the ripped fuel tank of the destroyed car. Only because of the quick reaction of some spectators present at the scene was Antônio Fernandes saved from being burned alive in his car. Even so, the deep injuries suffered by the driver in the accident would cost him his left leg, which was crushed in the impact. It was the sad end of the Portuguese driver's career.

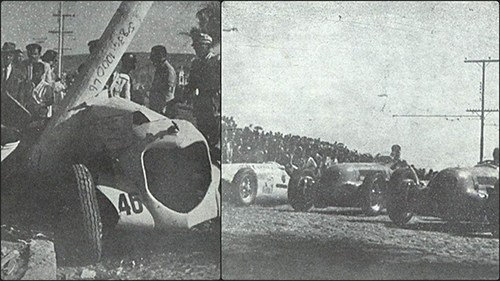

Pics of the dramatic race at Belo Horizonte. On the left, the destroyed car of Otacilio Rocha and, on the right, the moment of the start. (credits ACB)

Even so, the race continued at its pace: Landi was still leading, followed now by Francisco Marques. Further back, Gino Bianco, Otacílio Rocha, Amaral Junior and Raphael Gargiulino presented the crowd with a beautiful skirmish, with the GP and Adaptados machines having space to show their weaknesses and virtues in the different conditions offered by the circuit.

However, it would be from this group that the second big shock of the day would come. On the fourth lap, while Otacílio tried to overtake Bianco in one of the curves, the Hudson driver made a mistake and collided with the outer curb of the track. Otacilio lost control of the car, which bounced back towards the sidewalk and the crowd that was watching the race at the side of the track.

In a quick reflex to avoid a direct collision with the crowd, Otacílio turned his car and made it collide with an urban lamp post in the area. Parts of the car flew everywhere and the post, which had bent due to the impact, fell directly onto the Hudson's cockpit. Amaral Junior and Rafael Gargiulino, who, at that time, had fallen behind a little in the race, witnessed at first hand part of the chaos that followed the accident, when they had to dodge people who entered the track, fleeing from Otacilio's runaway car.

Despite being dragged out of the car shortly after the pole fell, Otacílio would die on the way to the hospital, due to the injuries suffered in the accident. And although some spectators were injured due to the debris scattered by the impact, the damage could have been much worse if Otacilio had not chosen to sacrifice his life and his vehicle in the collision with the pole in his last-ditch effort to stop the vehicle before crashing into the crowd.

However, despite the small physical damage to spectators, the psychological shatter from the two accidents was too much for the crowd present in Pampulha to bear. After the news of Otacilio's critical condition (the news of his death would only be confirmed the following day) pandemonium broke out in Belo Horizonte. People invaded the track, with civilians circulating indiscriminately between the cars, which were running at speeds exceeding 150kph.

The security deployed to guarantee the well-being of the crowd during the event was basically swallowed up by the number of spectators present, further overloading the small troops that were there. The members of the ACB present at the scene (among them the president of the institution and famous Brazilian driver, Manuel de Teffé), quickly realised that the race had gotten out of control and an immediate action had to be taken to avoid any other serious incident.

Rafael Gargiulino had a good overall performance in 1949, using a vehicle inferior to the de-facto GP cars. The driver's adapted Ford V8 proved to be a reliable machine in long-distance races. (credits unknown, colourised by the author)

Meanwhile, avoiding the crowd and other obstacles, the drivers continued to navigate through the tricky curves of the Pampulha circuit. Landi had managed to open a good gap over Marques from the fourth lap onwards, despite an unscheduled pit stop. As the driver rounded the track for the seventh time, Landi was informed that this would be the penultimate lap.

The ACB commission had initially wanted to reduce the number from 12 to 10 laps but due to the increasingly hostile conditions at the track and surroundings it was decided that as soon as the chequered flag was given, the chances of any other race-related casualties would be lower. And so the last lap unfolded, with Landi comfortably securing another victory to his impressive resume of national victories – despite this, it could be said that this was one of the most bitter, due to the general events of the race.

The driver completed the eight laps of the race in 1.23.13.7. Francisco Marques, who had also had a comfortable race in second place, crossed the finish line approximately two minutes behind Landi; and, completing the podium was Gino Bianco, already far behind the two leaders. Another interesting mark of Landi's is that he still holds the track record to this day, with a lap time of 9 minutes and 4 tenths.

Thus ended the first and only GP in the city of Belo Horizonte. The race which aimed to be one of the great stars of South American motorsport had turned into a great national embarrassment, which would tarnish the image of the state of Minas Gerais for years in its relations with the ACB.

Much of the criticism following the event in Pampulha came from some basic questions about the race. As pointed out in a post-race critical analysis, the event should never have happened under those circumstances. The Minas Gerais branch of the Automóvel Club do Brasil had little experience at the time in promoting motor races, and enthusiasm overcame logic in organising the contest.

This was completely against the guidelines of the Automóvel Club do Brasil at the time, which saw the growth of professionalism in motorsport in its neighbouring countries (especially Uruguay and Argentina), while Brazil was lurking behind in this dispute. The last thing the ACB wanted was negative publicity - and an event with a dead driver, another one seriously injured, as well a dozen stricken spectators, was not good at all for Brazil's image abroad.

Therefore, as a way of wanting to mitigate any future problems that might arise due to races like Pampulha, the ACB sought to concentrate its major events in the two main Brazilian centres: São Paulo and Rio. Not coincidentally, both had already become the main venues for Brazilian motorsport in the late 40s. In São Paulo, races would be held at Interlagos and on some street circuits; in Rio, it was the Gávea and Boa Vista circuits, together with the Governador Macedo Soares Trophy (held in Petrópolis, in the mountainous region of the state) that would form the basis of the ACB calendar for the following years.

As a final observation about the I Grande Prêmio da Cidade de Belo Horizonte, it clearly demonstrated the reasons why Brazil was losing space and prestige in the international automobile scene: the lack of planning, the disorganisation at a structural level, together with the delegation of critical functions to unprepared people; these ingredients, all mixed, formed a fatal combination in motorsport in the 40s and 50s.

Why to read me?

The years following the 1949 Temporada were a time of ups and downs for Brazilian motorsport. Due to its own responsibility and inability to adapt to new times, ACB ended up losing strength in the South American context, weakening the structure of the entire organisation to its roots. It is no wonder that, from the 1950s onwards, few Brazilians ventured into motorsport outside their home country (with the notable exceptions being 'Chico' Landi himself, Christian 'Bino' Heins and Fritz d'Orey).

But placing all the blame on the ACB would be an overly simplistic way of dealing with the challenges that Brazilian motorsport would face in the 1950s. Certainly, another major factor responsible for Brazil's loss of prestige as the epicentre of South American motorsport was the meteoric rise of Argentines on the international stage, driven by the spectacular generation of drivers that emerged in that country in the early 1950s.

Nothing like this had ever been seen outside of Europe, with so many high-skilled and talented drivers appearing in succession from a single country: Fangio, Gonzalez, Marimón, Mieres, Menditeguy, Galvéz, etc... For the simple fact that they appeared in a country outside the great traditional axis of motorsport, it was inevitable that all eyes would now turn to Argentina. Everyone, ranging from international press to the teams and manufacturers, wanted to know the magic formula that had given birth to so many talents on the pampas soil.

This photo, probably taken in 1952, presents two interesting characters from Brazil's automotive history: in the centre, Juscelino Kubitschek, while the man talking to him, on his right, is Henrique Casini. The car in the image is a Ferrari 166, a machine that Casini bought in 1952. (credits unknown, colourised by the author)

By the irony of fate, the Argentinians had a large presence in the last Brazilian Formula Libre Temporadas, between 1951 and 1952. They ended up being the big stars of these events, managing to snatch (comfortably) a good part of the victories in these races. Although the presence of these drivers was wonderful from a commercial point of view, with promoters and the public loving the possibility of watching in action the Argentine aces, it was an undeniable demonstration that Brazil had finally lost its place as the most prominent country in the terms of motorsport in the Southern Atlantic zone.

Another factor that was beyond the control of the ACB was the (re)institutionalisation of a centralised championship for GP-graded cars and drivers following, in part, the cast of the old AIACR European Championship from the pre-war years. The AIACR had given way to the FIA after WW2 as the highest governing body of world motorsport, and a major restructuring process was necessary, so that the institution could once again take control of the situation.