The Argentinian F2 Temporada of 1968

The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- July 12, 2023

Related articles

- 1949 Brazilian Temporada - Brazil's forgotten racing days, by Lorenzo Baer

- The 1960-1975 South African Drivers Championships - Grand Prix at the Cape, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/Rob Young

- 1966 Argentinian F3 Temporada - It's never too late to revive old passions, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1967 Argentinian F3 Temporada - Time to go south again!, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Rome GP - From Italy with love, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1969 Tasman Championship - Something that Chris Amon did win, by Tom Prankerd

- 1970-1975 Tasman Championship - Back to Pukehoke for a revival of F5000 Tasman days, by Gareth Evans

- 1971 Colombian F2 Temporada - When Formula cars roared in the Coffee Land, by Lorenzo Baer

- Cuba, Bahamas, Puerto Rico - Racing Juniors in the tropics, by Lorenzo Baer

Why?

The fifties represented the pinnacle of Argentine motorsport: talented drivers such as Juan Manuel Fangio, Froilαn Gonzalez, Roberto Mieres and Carlos Menditeguy dominated the highest category, even with challengers of no lesser level; Buenos Aires was a mandatory stop on the F1 route, as an official stage for most of the decade.

But over the years and races, the circle slowly contracted until there was nothing left. Until the early 1960s, all traces of a visit by the motor racing masters to the land of tango disappeared, as interest turned more and more to Europe and Oceania. Something had to be done, and fast, to realign the bent axle.

The big opportunity came in the second half of the sixties, with the rapid development that not only permeated F1, but the entire scope of adjacent categories. If F1 became an increasingly expensive and professional sport, with even the traditional circuits pondering over holding a round, F2 and F3 became the junction between the training of the 'professional driver', with the financial accessibility. If we take into account that in the 60s, many of the F1 drivers participated in races in lower categories, it was perfect for teams and individuals with less financial support to give a try in these categories: quality, quantity, equity and accessibility, became the motto of F2 and F3 at the end of the decade.

Another reason for the development of F2 at that time is presented in a more technical-mechanical element: if we can say that if the Internet transformed communication as we know it today, we can say that the Cosworth engine did the same for motorsport in the sixties. The democratization of this small but powerful engine allowed everyone to have something competitive, relatively reliable and at a negligible cost, compared to the tens of thousands of pounds that top teams spent on the developing of engines in the Grand Prix scene.

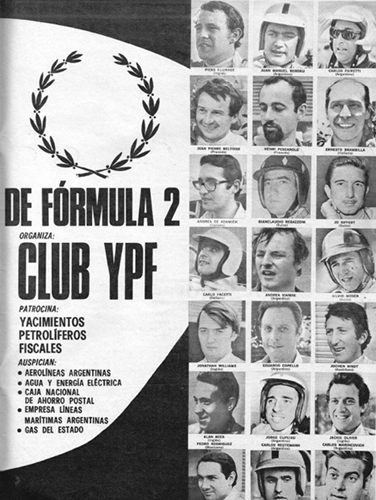

The series poster.

Putting this together with the expansion of F1 as a global sport, we arrive at the year 1968. Graham Hill had already been crowded World Champion; in F2, Jochen Rindt had dominated, even without winning the 'title', with five wins - which only served to reinforce his image of being champion of the top category of motorsport in the very near future.

So, Argentina got ready to receive the championship that would put it back on the map in style: four rounds in three different locations. Whoever scored the most points at the end would be the champion of the 1968 Argentine F2 season. It is worth noting that, even though it was still held in 1968, this season already counted as a pre-season for 1969!

The organizer of this undertaking could not be less than the Argentine legend Juan Manuel Fangio, who had won five F1 world titles in the 1950s. The financial support would come from the state-owned YPF (Yacimientos Petrolνferos Fiscales), the company responsible for extracting and refining oil in Argentina.

Matra came to Argentina to test an array of wing configurations. Here is Pescarolo's Matra sporting a high aerofoil. (photo Francisco Bruno)

A pompous list of drivers and teams attended the small championship: the Matra Sports team, with its French squadron of Beltoise and Pescarolo. Frank Williams, with the team that carried his name, was composed by the experienced Piers Courage, and a trio of Argentines: Juan-Manuel Bordeau, Carlos Pairetti and 'Cacho' Fangio. Also made up mostly of Argentines was the Ron Harris Racing Division: a relatively unknown Carlos Reutemann shared the role with Oscar-Mauricio Franco and Carlos Marincovich; they had the leadership of the flying Mexican, Pedro Rodriguez. Roy Winckelmann was also part of the European exodus to the south, carrying with him an experienced team of drivers: Jochen Rindt, who needed no introduction, and the Englishman Alan Rees. Another highlight was the official Tecno team, which had been so successful in Europe with its self-made chassis, in addition to those sold to privateers; the factory cars were guided by Joseph Siffert, who had his great moment in F1 in 1968 and who joined the team only for the Argentine season, in addition to Carlo Facetti and the Swiss who would bother so much in F1 in the seventies: Clay Regazzoni. Together with these, several other smaller teams and wildcard entries (even by F2 standards) would make up the grid, closing up the final list of 21 cars.

If the biggest difference between all these cars was the chassis, which basically varied between the dominant Matra MS7, Brabham BT23C and Tecno T68, the engine was the same venerable Ford Cosworth FVA 1.6 L4. But, as always in motorsport, there was the exception: the Maranello team, which had so many ups and downs in the 1968 F1 and F2 season, took its venerable Dinos, in the F2 166 chassis, in response. It was perhaps not a fight of David versus Goliath, but almost a Battle of Thermopylae. It was up to the Italian duo of Ernesto 'Tino' Brambilla and Andrea de Adamich to hold the momentum of the Cosworths, with only two cars.

1. Gran Premio Gas del Estado (Buenos Aires, variant n° 9)

The first teams began to arrive in Argentina on November 25th, going to the race track that so many stars had seen in the fifties. When they left the circuit, Ron Harris, in an enthusiastic mood, even talked about the possibility of Tecno entering as an F1 team in 1969 (something which obviously didn't happen): "Initially, the plans are to start with a Cosworth engine. Afterwards, we will move on to an Alfa Romeo engine, to form an all-Italian team" (Revista Automundo, December 2, 68, vol 187).

The Ferraris surprised the crowd, shading most of the competition in the first race of the Temporada - De Adamich (#14) and Brambilla (#12) were second and third on the starting grid.

The great transformations that occurred in F1 during 1968 began to influence F2 designs, mainly with the understanding of the importance of aerodynamics, with the introduction of wings/ailerons in the cars designs. Practically all cars had some modification in this sense, albeit in a primitive way; some, like the Ferrari and Lotus ones, were appreciated by the reporters present at the place; others were suspect. Especially at Brabham, where some experts feared the device's appearance as much as it was fragile.

On Wednesday morning (of the race week), the testing sessions began but not before a misunderstanding occurred: Carlos Reutemann, who would be the first to start the laps on the circuit, was stopped by shouts, when leaving the pit, by members of the Automσvil Club Argentino (ACA). This happened because the cars had not yet been released by the country's customs to enter the track, and mechanics were only allowed to assemble and check the state of the machines after the trip to the southern hemisphere! But, as always when it comes to motorsport, misunderstandings are soon resolved and Copello, Bordeau, Reutemann and Pairetti used the rest of the day for a reconnaissance of the terrain.

And disaster almost struck the circle on its first day, around 7pm, when Pairetti himself, on a quick test lap near the Tobogγ, lost control of his car and crashed into one of the circuit's protective barriers. The car burst into flames, the Brabham BT23C being completely consumed by fire. The accident did not cost the driver's life, who was almost unharmed, but his chances of taking part in the first round of the season were gone.

The big disappointment of the Temporada was undoubtedly Pedro Rodriguez (#38). With the exception of fifth place in the first race, the other three legs were miserable for the Mexican driver. (photo LAT Photographics)

As the big European stars arrived at the circuit, the times dropped more and more, with the highest caliber drivers adapting to the fast circuit of the Argentine capital. With the end of the test sessions and the official timing sessions, the first row was defined by Roy Winckelmann's Brabham of Jochen Rindt in first position, followed promptly by the two Ferraris of De Adamich and Brambilla.

Even with the best time, Jochen Rindt feared for the reliability of his car, as evidenced by this small speech given to the Argentine press, after securing the first position: "I'm not sure if I can win any of these races in Argentina. The Ferraris have the speed. It seems that, in the end, they will set the pace. Furthermore, they have better 'shoes'. Firestone currently makes the best tyres for F1 and F2." In five short sentences, Rindt gave the clue of what was going to happen in the four races to come.

The start, on that sunny Sunday, went smoothly, except for the general disappointment of the Argentine fans, who on the first lap saw the retirement of Eduardo Copello, the second best Argentine in qualifying, with clutch problems. The development of the race resulted in three main blocks of vehicles: Rindt, Brambilla and De Adamich, opening up an advantage on the pursuers Oliver, Regazzoni and Courage. Further back, Pedro Rodrigues, Pescarolo and Siffert, who just followed their pace, without threatening the trio further ahead, and without being threatened by the remaining Argentine riders who came behind.

The supremacy of the Ferraris soon became evident as both overtook Rindt's Brabham without giving the Austrian a chance to respond. On lap 24, the Italian pair's race became a mere drive to the finish line when Rindt's car began to experience problems with its aileron system and was forced to retire. He joined the aforementioned Copello, Reutemann (lap 2, crash), Jean-Pierre Beltoise (lap 15, cylinder joint) and Silvio Moser (lap 16, axle), as visitors to the pits in the first half of the race.

The race 1 results in a nutshell.

While the Italian pair opened up an advantage, Jackie Oliver emerged as the favorite for third place on the podium, when another Brabham, this time Piers Courage, was forced to stop in the pits due to oil system problems. Regazzoni followed behind Oliver, giving a high chase from time to time, but without posing a real threat to the British driver of the Lotus.

And in this small procession, with Ernesto Brambilla in the lead, closely followed by Adamich's squire, the race ended, completing 70 laps in 1h 35' 20. In addition to being the race winner, Brambilla set the fastest lap, with 1m19.500, with an average speed of 152,304 km/h.

Final standings (race n° 1)

| 1. | Ernesto Brambilla (#12) | Ferrari Dino | 1h3520 | 70 laps |

| 2. | Andrea de Adamich (#14) | Ferrari Dino | 1h3520 | 70 laps |

| 3. | Jackie Oliver (#36) | Lotus Cosworth | 1h3620 | 70 laps |

| 4. | Clay Regazoni (#16) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h3639 | 70 laps |

| 5. | Henri Pescarolo (#10) | Matra Cosworth | 1h3544 | 69 laps |

| 6. | Pedro Rodriguez (#38) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h3617 | 69 laps |

| 7. | Juan Manuel Bordeu (#4) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3529 | 68 laps |

| 8. | Carlo Facetti (#20) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h3549 | 68 laps |

| 9. | Andrea Vianini (#22) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h3612 | 68 laps |

| 10. | Alan Rees (# 32) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3642 | 66 laps |

Not classified

| 11. | Jorge Cupeiro (#34) | Brabham Cosworth | not classified | 62 laps |

| 12. | Jonathan Williams (#26) | De Tomaso Cosworth | right rear suspension | 53 laps |

| 13. | Piers Courage (#2) | Brabham Cosworth | oil system | 29 laps |

| 14. | Jo Siffert (#18) | Tecno Cosworth | fire | 25 laps |

| 15. | Jochen Rindt (#30) | Brabham Cosworth | rear ailerons | 24 laps |

| 16. | Silvio Moser (#24) | Tecno Cosworth | axle | 16 laps |

| 17. | Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#8) | Matra Cosworth | cylinder joint | 15 laps |

| 18. | Carlos Reutemann (#40) | Tecno Cosworth | accident | 2 laps |

| 19. | Eduardo Copello (#28) | Brabham Cosworth | clutch | 1 lap |

| 20. | Carlos Marincovich (#42) | Tecno Cosworth | did not start | 0 laps |

| 21. | Carlos Pairetti (#6) | Brabham Cosworth | accident in test session | 0 laps |

2. Gran Premio Lνneas Marνtimas Argentinas (Cσrdoba, Oscar Cabalιn)

On Saturday morning, before the first race in Buenos Aires, De Adamich told the Argentine press: "Tomorrow, you will be able to see four men who will drive together fighting for the lead: the rest will stay behind. The circuit is not very friendly to 'fierce' racing as we see in Europe where 10 to 12 cars run inches apart. This could perhaps happen in Cσrdoba, which is a much faster track." After seeing the second round, it seems that the Italian driver's words were prophetic.

The Oscar Cabalιn race track, located on the outskirts of the capital of the province of Cσrdoba, was set to be the best race of the season, mainly because the 3,202-metre track resembles a rectangle, offering chances of overtaking at almost every point of the circuit. Even with some more technical points, mainly in the last sector before the finish line, the race would be more of a test for the machines than for the drivers themselves.

The order of favorites, however, had not changed since Buenos Aires: the Ferrari team, with its Dinos increasingly acclimatised to Argentina, had a small advantage, while the Austrian Jochen Rindt was the only one to truly challenge Italian dominance. One of the reasons most pointed out by technicians at the time was the marginal power advantage that the Dino engines possessed over the Cosworths (230hp x 220hp), in addition to the superior torque of the Ferrari engine, since it was a V6. You must remember that the Cosworths were four-pots.

Even with the superiority of the three drivers over the rest of the field, the driver who secured first place on the starting grid was the surprising Swiss Clay Regazzoni, with a time almost equal to the second placed driver, Andrea de Adamich. Both set a time of 58s100, but Regazzoni had the right to start from pole. In third place was Piers Courage. Rindt would start in fourth place, while after a bad qualifying session, Brambilla would start from 14th.

In the second race of the season, Cupeiro leads Rodriguez who is followed by Copello and Bordeu.

Closing up are Rees and Facetti.

But after the official start of the race, the grid was soon torn apart, taking the form of the dispute that would mark the championship: De Adamich soon overcoming his opponents on the front row to quickly take the lead while Jochen Rindt followed in his wake. Behind, a small group composed by the Matras of Beltoise and Pescarolo, together with the Brabham from Courage and the Tecno of Regazzoni.

This small group of four drivers piloting cars from three different brands presented a spectacle of their own, in the fight that would last for 70 laps. The balance between the engines, which were basically the same, did not allow for the possibility of much overtaking; because any mistake would be fatal in the dispute. Thus, with the focus of the four on not making mistakes and handing opportunities to their opponents in the group, it allowed Vianini and Siffert to approach, reducing the difference to a few seconds. Even so, it wasn't enough to threaten the quartet ahead.

Regazzoni (#16), Courage (#2) and Pescarolo (#10) in a small skirmish during one of the races, probably at Cσrdoba. (credits Car Racing 1968 and DPPI)

The only other serious dispute that took place on the track was closer to the end, between British drivers Jackie Oliver and Jonathan Williams, who fought a singular duel between a Lotus 48 and a De Tomaso. One observation about the De Tomaso is that it was nothing more than a refined Tecno chassis with modifications to the front suspension and rear aerodynamics of the car, made by former racing driver and automotive designer Alejandro de Tomaso.

At this rate, in small skirmishes, the race went on. Rindt, with his characteristic style of driving, threatened De Adamich in a fast way, who held the Austrian with an advantage that varied between 2 to 6 seconds. And with the retirement of Brambilla, on lap 46, there was only one Ferrari left on the track facing the horde of Cosworths. But the Dino engine found its ideal environment in Argentina, and no more than one car was needed to secure victory.

The race 2 results in a nutshell.

Andrea de Adamich crossed the finish line in first place after 1h9'22", four seconds ahead of Jochen Rindt. Completing the podium was Frenchman Henri Pescarolo. The fastest lap was credited to Piers Courage, with 56100, at an average speed of 196.197kph.

Another curiosity is that even though it was a fast circuit, with lap times of less than 1 minute, eight of the twenty cars that started managed to finish on the leader's lap, which is a huge number compared to other races.

Final standings (race n° 1)

| 1. | Andrea de Adamich (#14) | Ferrari Dino | 1h0922 | 70 laps |

| 2. | Jochen Rindt (#30) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h0926 | 70 laps |

| 3. | Henri Pescarolo (#10) | Matra Cosworth | 1h0930 | 70 laps |

| 4. | Clay Regazoni (#16) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h0931 | 70 laps |

| 5. | Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#8) | Matra Cosworth | 1h0932 | 70 laps |

| 6. | Piers Courage (#2) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h0933 | 70 laps |

| 7. | Jo Siffert (#18) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h1006 | 70 laps |

| 8. | Andrea Vianini (#22) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h1015 | 70 laps |

| 9. | Pedro Rodriguez (#38) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h0928 | 69 laps |

| 10. | Jackie Oliver (#36) | Lotus Cosworth | 1h0953 | 69 laps |

| 11. | Jonathan Williams (#26) | De Tomaso Cosworth | 1h953 | 69 laps |

| 12. | Carlo Facetti (#20) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h925 | 68 laps |

| 13. | Alan Rees (#32) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h924 | 65 laps |

Not classified

| 14. | Juan Manuel Bordeu (#4) | Brabham Cosworth | not classified | 61 laps |

| 15. | Ernesto Brambilla (#12) | Ferrari Dino | engine | 46 laps |

| 16. | Silvio Moser (#24) | Tecno Cosworth | injection | 34 laps |

| 17. | Carlos Reutemann (#40) | Tecno Cosworth | connecting rod disconnect | 25 laps |

| 18. | Eduardo Copello (#28) | Brabham Cosworth | engine | 12 laps |

| 19. | Jorge Cupeiro (#34) | Brabham Cosworth | engine | 8 laps |

| 20. | Carlos Marincovich (#42) | Tecno Cosworth | oil pressure | 6 laps |

| 21. | Carlos Pairetti (#6) | Brabham Cosworth | car not ready | 0 laps |

3. Gran Premio Empresas Agua y Energia Eletrica (San Juan, Zonda)

A new round, a new track, new challenges. The championship now moved to the unique Zonda circuit in the province of San Juan. Perhaps more than the circuit itself, the scenery was something that was spectacular for the drivers. The track, almost in the shape of a flattened figure 8, was located in the foothills of the Andes, being almost swallowed by the mountain chain.

Despite winning the first race in Buenos Aires, Tino Brambilla suffered from reliability problems with the Ferrari in the remaining three races of the Temporada.

Inaugurated just a year earlier, the track had become one of the main centres of Argentine motor racing, having already hosted touring and Carretera races. But now, with the first event at an international level, the true test of the venue would take place.

The first session of tests and reconnaissance of the track, which even for the Argentine drivers was quite unknown, took place on Wednesday. To the surprise of no-one, two of the first four positions were taken by Ferrari drivers. De Adamich in second, Brambilla in fourth, but the fastest was Swiss Jo 'Seppi' Siffert, in a factory Tecno 68.

Beautiful panorama of the San Juan circuit during the F2 race. Certainly, the drivers were fascinated by the sight of the Quebrada de Zonda, the mountain range that frames the circuit. (photo LAT Photographics)

However, on the eve of the race, when the qualifying times were to be set, the circuit at the base of the Andes gave its first sample of unpredictability when very strong winds swept the track, preventing any activity on the part of the drivers. Because of this, all timing sessions were cancelled, and the times set on Wednesday were used as a substitute for grid assembly!

While for some this was very welcome news, for others it was the worst thing that could have happened: Jochen Rindt, who had been late leaving Cσrdoba, had not been able to arrive in time for the session that took place in the middle of of the week, betting everything on qualifying on Saturday in the end, the gamble ended up backfiring, and the Austrian driver who had been the main challenger for Scuderia Ferrari during the first two races would start from last position of the grid.

Thus, two Ferraris, one Tecno and one Matra would start from the first four positions, with Jean-Pierre Beltoise starting from third. The best driver in the nation that hosted the event was Andrea Vianini, starting only in 12th position which demonstrated the great gap between the most experienced drivers who lived on the European 'circuit' with those who were on the periphery of motorsport.

Jorge Cupeiro (#34) had another difficult race at San Juan. The driver only finished in 12th position out of the 14 final classified finishers. (photo LAT Photographics)

With the wind gone and a beautiful sun reflecting on the mountains that framed the circuit that December 15th, the flag was dropped and the 21 cars that made up the grid took off, lighting up the San Juan valley with the sound of F2 engines. As had become customary, the Ferraris shot into the lead but this time in the company of Beltoise's sky-blue car. The Frenchman had taken Rindt's place in that race of being the nuisance of the Maranello duo. Disputing corner by corner with the Italian drivers, Beltoise in a certain point of the race managed to overtake both Ferraris, leading, even if in an ephemeral way, the race.

Andrea Vianini (#22), Clay Regazzoni (#16) and Piers Courage (#2) fight for the positions in San Juan.

(photo LAT Photographics)

Behind the trio, a fight between the Swiss duo Regazzoni and Siffert developed, with no margin of advantage between one and the other driver: it is worth remembering that both drivers were members of the official Tecno team, and the cars, therefore, were practically identical.

It was more about the driver's skill and his intimacy with the car than the mechanical factors themselves. While Siffert sought to be more technical, in the sense of waiting for the right moments to brake and pass the stragglers on the track, interposing an obstacle between him and his teammate, Regazzoni applied a more aggressive driving, pushing his Tecno to the limit, sliding the rear around to seek maximum traction and track space. The skirmish had become so close that it allowed Jackie Oliver and his sneaky Lotus to close in and quickly get between the teammates.

But if Regazzoni and Siffert didn't even see Oliver's approach, much less did they observe Rindt's furious charge through the grid who due to retirements and his own skill managed to reach fourth place in the race.

The race 3 results in a nutshell.

And as was his nature, the Roy Winkelmann Racing driver would not be content with staying a step away from the podium. This time, with a bit of luck, fourth place became third, when Brambilla's Ferrari made a definitive stop in the pits, with engine valve problems, on the 37th lap.

Because of this too, the battle between the front trio of Ferraris and the Matra became an old-fashioned duel, with each driver looking for the best position to deal a definitive blow to their opponent. And so it was when De Adamich managed to create a small advantage that gave the driver the peace of mind to cross the finish line first, 18 seconds ahead of the brave Beltoise, who demonstrated his best performance so far in the Argentine F2 season. Rindt came in third having set the best lap time of the race as a consolation prize: 1m08.300, with an average speed of 170.247kph.

Final standings (race n° 1)

| 1. | Andrea de Adamich (#14) | Ferrari Dino | 1h2146 | 70 laps |

| 2. | Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#8) | Matra Cosworth | 1h2204 | 70 laps |

| 3. | Jochen Rindt (#30) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h2215 | 70 laps |

| 4. | Jo Siffert (#18) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h2220 | 70 laps |

| 5. | Jackie Oliver (#36) | Lotus Cosworth | 1h2245 | 70 laps |

| 6. | Clay Regazzoni (#16) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h2252 | 70 laps |

| 7. | Carlo Facetti (#20) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h2234 | 69 laps |

| 8. | Eduardo Copello (#26) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h2220 | 68 laps |

| 9. | Pedro Rodriguez (#38) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h2231 | 68 laps |

| 10. | Juan Manuel Bordeu (#4) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h2153 | 67 laps |

| 11. | Andrea Vianini (#22) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h2154 | 67 laps |

| 12. | Jorge Cupeiro (#34) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h2230 | 67 laps |

| 13. | Henri Pescarolo (#10) | Matra Cosworth | 1h2244 | 65 laps |

| 14. | Jonathan Williams (#26) | De Tomaso Cosworth | 1h2227 | 63 laps |

Not classified

| 15. | Alan Rees (#32) | Brabham Cosworth | not classified | 62 laps |

| 16. | Piers Courage (#2) | Brabham Cosworth | engine | 59 laps |

| 17. | Ernesto Brambilla (#12) | Ferrari Dino | engine valves | 37 laps |

| 18. | Carlos Marincovich (#42) | Tecno Cosworth | injection | 16 laps |

| 19. | Silvio Moser (#24) | Tecno Cosworth | front suspension | 5 laps |

| 20. | Carlos Reutemann (#40) | Tecno Cosworth | engine fire | 3 laps |

| 21. | Carlos Pairetti (#6) | Brabham Cosworth | oil loss | 1 lap |

The drivers would now return to the Portenγ capital and the famous Buenos Aires circuit, for the last round of the 1968 Argentine F2 season.

4. Gran Premio Aerolineas Argentines (Buenos Aires, Variant n° 6)

The location of the last championship race would be the same as the first, but the similarities stop right there. In the December 1st presentation, the race was held on the variant of the circuit called n° 9, with 3,413 metres in length, but for the climax of the season the variant chosen was n°6, with 4,208 metres.

For those who saw or perhaps remember any of the F1 championships between 1995 and 1998, this was the same variant that hosted the final moment of the Argentine F2 season in 1968. With the exception of the modifications due to the development in safety during three decades, you can say that circuit n°6 has seen on its surface both Tecnos and Minardis!

In any case, the difference between the two variants used in the Argentine season was quite stark, not simply translating into the lap distance value: while variant n°9 was basically a high-speed circuit, with only one slower section (between curves 3 Entrada a Los Mixtos and 9 Salida del Tobogγ), variant 6 would demand much more from the drivers' technical skills, as the Salida del Siervo was crossed, giving way to another sequence of curves in the heart of the circuit best known as the Confiterνa.

Therefore, everyone once again expected the dominance of Ferrari, which had demonstrated its supremacy on all circuits so far. Both in straight-line speed and cornering agility, the scarlet-red cars were the ones that had dictated the pace of all races so far. Hard to imagine this before the start of the championship, as they came as dark horses after the turbulent years of 1967 and 1968.

Much of this was due to the watchful eye of the Italian team of engineers led by the almost mythological Mauro Forghieri. When resources were given and focus was directed, Ferrari's full competence was demonstrated on the track but, as is known, at the end of the sixties, the Scuderia's effort was divided between Formula 1 and Formula 2 cars, touring cars, prototypes for endurance racing, and road cars. Is it worth asking how many victories that cost? We will never know but the question is up in the air.

The FA68, the first car from the Italian constructor Tecno built for the F2 regulations, proved to be a very competitive machine. Here, Jo Siffert in the last round of the Temporada.

Anyway, at least at the end of 1968, the Scuderia regained some of its lost glory and respect. Already in the official timing session on the Saturday before the race, Brambilla and De Adamich were the fastest, ensuring the two Ferraris once again their spots on the front row. In third place, Jochen Rindt was again playing the role of tormentor for the Italian duo - even if he set a lap time almost 1 second slower.

Even from the front of the starting grid, Ferrari's mood deteriorated rapidly during the afternoon, as is so typical of the Italian team, as the news of Andrea de Adamich's non-renewal with the Maranello team, and his migration to rivaling Alfa Romeo was dropped like a bomb in the pits. After the Argentine press had discoved and unveiled the news, the driver was enraged, and De Adamich's chagrin was further heightened when he discovered that it was Enzo Ferrari who had leaked the information at a press conference in Modena a week earlier.

Carlos Reutemann was the best Argentine in the standings, starting in 11th position. Born in the Argentine province of Santa Fι in the northeast of the country, the hitherto unknown on the international scene had not had much luck in the championship. He had proven to be fast in qualifying but when it came to racing, the combination of bad luck and inferior equipment had cost him the chance to better demonstrate his skills against the more experienced European drivers.

The race scheduled for December 22 would be held in a different way from the previous three rounds, as instead of one full sprint race pattern, the last round was reserved for a scheme of two heats, each having 25 laps. The driver with the smallest aggregate of time from both heats would be the winner.

Rindt, De Adamich and Brambilla lined-up for heat 1 of the last race of the season.

Given the start of the first heat, it seemed that the plot of the last few races would repeat itself once again: De Adamich's Ferrari in first, then came Brambilla; followed by Jochen Rindt's Brabham. Another driver who demonstrated that he had a car to match in the final round was Jo Siffert, who was following the first group.

Another one showing an eagerness to stand out from the rest was Englishman Piers Courage, who tried to maintain a consistent pace, keeping in sight the four drivers who were battling ahead and opening a gap from the skirmish that followed right behind between Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Jackie Oliver. Matra, that for the first time was testing high-mounted wings on its cars, showed inconsistent performance, as its drivers were still adapting to the new technology.

At one point, Beltoise and Oliver came to blows violently, causing part of the rear fairing of Oliver's Lotus to detach from the car, but nothing that disturbed the quarrel between the two drivers who continued to punish each other throughout the first heat.

Right behind, to the happiness of the Argentine crowd, finally a national driver began to emerge in the championship as Reutemann grappled with Regazzoni in a fight that proved to be spectacular for the audience: even though the Argentine was unable to overtake the Swiss, for more than ten laps Reutemann poked his nose in a threatening way, from one side to the other, towards Regazzoni's Tecno. The Swiss driver, however, was not easily scared and soaked up the pressure until the end of the first heat. However, Reutemann had already given his calling card.

Carlos Reutemann was the highlight of the Argentinian drivers in the Temporada. It wouldn't be long before the driver began his journey into the big circle of F1.

Just as a Ferrari one-two was already taken for granted in the first heat, bad luck struck Tino Brambilla once again: the driver leading the race on the final lap heard his engine falter before a dull explosion followed from the engine, and it was all over. An oil leak had destroyed the engine, and the disconsolate driver who had had so much bad luck in the last three races said goodbye to the land of tango.

The driver taking advantage of the problem was De Adamich who, passing through the entrance to Los Mixtos, saw his teammate's despair, and having nothing to do with it, continued accelerating and crossed the finish line with a time of 4814.200, almost six seconds ahead of Rindt. Third was Siffert, with Piers Courage less than three tenths of a second behind.

Standings heat 1

| 1. | Andrea de Adamich (#14) | Ferrari Dino | 4814 | 25 laps |

| 2. | Jochen Rindt (#30) | Brabham Cosworth | 4820 | 25 laps |

| 3. | Jo Siffert (#18) | Tecno Cosworth | 4822 | 25 laps |

| 4. | Piers Courage (#2) | Brabham Cosworth | 4823 | 25 laps |

| 5. | Jackie Oliver (#36) | Lotus Cosworth | 4842 | 25 laps |

| 6. | Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#8) | Matra Cosworth | 4846 | 25 laps |

| 7. | Clay Regazzoni (#16) | Tecno Cosworth | 4858 | 25 laps |

| 8. | Carlos Reutemann (#28) | Brabham Cosworth | 4858 | 25 laps |

| 9. | Henri Pescarolo (#10) | Matra Cosworth | 4920 | 25 laps |

| 10. | Juan Manuel Bordeu (#4) | Brabham Cosworth | 4930 | 25 laps |

| 11. | Jorge Cupeiro (#34) | Brabham Cosworth | 4938 | 25 laps |

| 12. | Jonathan Williams (#26) | De Tomaso Cosworth | 4944 | 25 laps |

| 13. | Andrea Vianini (#22) | Tecno Cosworth | 4950 | 25 laps |

| 14. | Oscar Mauricio Franco (#40) | Tecno Cosworth | 5004 | 25 laps |

| 15. | Ernesto Brambilla (#12) | Ferrari Dino | 4617 | 24 laps |

| 16. | Alan Rees (#32) | Brabham Cosworth | 4848 | 24 laps |

| 17. | 'Cacho' Fangio (#6) | Brabham Cosworth | 4929 | 23 laps |

| 18. | Silvio Moser (#24) | Tecno Cosworth | 3054 | 15 laps |

| 19. | Carlo Facetti (#20) | Tecno Cosworth | 1326 | 6 laps |

| 20. | Carlos Marincovich (#42) | Tecno Cosworth | 1230 | 5 laps |

| 21. | Pedro Rodriguez (# 38) | Tecno Cosworth | 2218 | 2 laps |

End of the first heat, and the preparation for the second one was already in full swing. But even before that could happen, bad luck struck Scuderia Ferrari again. At the start of the second heat, a confusing accident occurred.

De Adamich lost control of his car when he accelerated after the start clearance, heading towards a group of guests and drivers who were standing in the pits. Without having time to react, the Ferrari driver hit directly a group of people standing in the pits, injuring half a dozen people who were in the place, including reporters, spectators and even fellow driver Carlos Marincovich. Confusion settled in the pits, with the police asking for the postponement of the race while other people wanted to go after the Italian driver, to have a little 'chat' with him.

In the end, the conclusion was that the accident was due to a touch on the rear of the car (with Reutemann or Courage as the main suspects) causing a small mechanical balance change that put the car out of control. Both De Adamich and the Ferrari car emerged, at least outwardly, almost intact from the accident, even with half a lap behind the main group. Internally, however, the damage had been done, as would be seen in the second heat.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise ended up in sixth and fifth in the final two races, his Matra equipped with the low rear wing mounted in front of the rear axle. (photo Francisco Bruno)

After calming down and removing the wounded, the race continued at its pace. And, to everyone's surprise, this time it wasn't red that was leading the race: it was British Racing Green, traditional for the Brabham cars. Now, it was finally Rindt's turn to win a victory in Argentine lands! But sometimes, the story likes to be unpredictable, putting a dash of drama where ever possible.

Behind the Austrian followed in order Siffert, Oliver, Courage and the surprising Reutemann who drove like an experienced driver. However, the joy of the Argentine driver would not last long in this second heat when after completing six laps the Brabham refused to continue, suffering from oil pressure problems.

While Rindt was looking for peace of mind in the race, something he hadn't had so far in the championship, another Brabham was chasing him. After jostling for position with Siffert and Oliver for most of the second heat, Piers Courage had broken free from the duo and was now attacking the leader of the race.

Briton Piers Courage was the only one who managed to break the streak of Ferrari wins in Argentina.

From then on the race began to be a seesaw of emotions. First, Jochen Rindt, who had gained a good margin of time ahead of the pursuers, began to have engine problems: he was losing time in the lower gears, which was precious on the twisty circuit of Buenos Aires. With that, the three drivers behind began to close the gap. Jo Siffert, who had the third best combined times (behind De Adamich and Rindt), relied on the problems of both drivers to take first position overall.

However, on the final lap, Siffert started to slow down, which cost him precious seconds on aggregate the official excuse was that Siffert's car started to have the same problem as Rindt's, the unofficial, which was commented at the time, was that 'Seppi' ended up getting confused in the lap count thinking that he had already completed the 25 laps of the second heat when, in fact, there was one still remaining.

Who best capitalised on the problems of all his direct opponents was Englishman Piers Courage who surreptitiously took first position in the race, holding it until the final flag. Jackie Oliver and his Lotus crossed the line in second, in third and fourth were the faltering Jochen Rindt and Jo Siffert, respectively.

Standings heat 2

| 1. | Piers Courage (#2) | Brabham Cosworth | 4854 | 25 laps |

| 2. | Jackie Oliver (#36) | Lotus Cosworth | 4902 | 25 laps |

| 3. | Jochen Rindt (#30) | Brabham Cosworth | 4907 | 25 laps |

| 4. | Jo Siffert (#18) | Tecno Cosworth | 4916 | 25 laps |

| 5. | Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#8) | Matra Cosworth | 4932 | 25 laps |

| 6. | Andrea de Adamich (#14) | Ferrari Dino | 4935 | 25 laps |

| 7. | Andrea Vianini (#22) | Tecno Cosworth | 4936 | 25 laps |

| 8. | Jorge Cupeiro (#34) | Brabham Cosworth | 4938 | 25 laps |

| 9. | Henri Pescarolo (#10) | Matra Cosworth | 4945 | 25 laps |

| 10. | Juan Manuel Bordeu (#4) | Brabham Cosworth | 4955 | 25 laps |

| 11. | Alan Rees (#32) | Brabham Cosworth | 5037 | 25 laps |

| 12. | Jonathan Williams (#26) | De Tomaso Cosworth | 4024 | 20 laps |

Not classified

| 13. | Carlos Reutemann (#28) | Brabham Cosworth | oil pressure | 6 laps |

| 14. | 'Cacho' Fangio (#6) | Brabham Cosworth | oil pressure | 6 laps |

| 15. | Oscar Mauricio Franco (#40) | Tecno Cosworth | clutch | 3 laps |

| 16. | Clay Regazzoni (#16) | Tecno Cosworth | gearbox | 2 laps |

| 17. | Ernesto Brambilla (#12) | Ferrari Dino | engine | 0 laps |

| 18. | Silvio Moser (#24) | Tecno Cosworth | bearing | 0 laps |

| 19. | Carlo Facetti (#20) | Tecno Cosworth | transmission | 0 laps |

| 20. | Carlos Marincovich (#42) | Tecno Cosworth | oil pressure | 0 laps |

| 21. | Pedro Rodriguez (#38) | Tecno Cosworth | injection | 0 laps |

After the times of both heats were combined, Piers Courage was declared the winner of the fourth round of the season with a total time of 1h37'17", 10 seconds less than second placed driver Jochen Rindt. The only qualified Ferrari was Andrea de Adamich, in 5th position overall.

This was Piers Courage's first F2 win, but not the car's first time. On June 23rd, 1968, in the European F2 championship, Jonathan Williams had already taken the BT23C-7 chassis to victory in the X Gran Premio della Lotteria di Monza.

Final standings after both heats (race n° 4)

| 1. | Piers Courage (#2) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3717 | 70 laps |

| 2. | Jochen Rindt (#30) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3727 | 70 laps |

| 3. | Jo Siffert (#18) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h3739 | 70 laps |

| 4. | Jackie Oliver (#36) | Lotus Cosworth | 1h3745 | 70 laps |

| 5. | Andrea de Adamich (#14) | Ferrari Dino | 1h3749 | 70 laps |

| 6. | Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#14) | Matra Cosworth | 1h3819 | 70 laps |

| 7. | Henri Pescarolo (#10) | Matra Cosworth | 1h3906 | 69 laps |

| 8. | Jorge Cupeiro (#34) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3916 | 68 laps |

| 9. | Juan Manuel Bordeu (#4) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3925 | 68 laps |

| 10. | Andrea Vianini (#22) | Tecno Cosworth | 1h3926 | 67 laps |

| 11. | Alan Rees (#32) | Brabham Cosworth | 1h3926 | 67 laps |

| 12. | Jonathan Williams (#26) | De Tomaso Cosworth | 1h3009 | 67 laps |

| 13. | Carlos Reutemann (#28) | Brabham Cosworth | no time | 31 laps |

| 14. | 'Cacho' Fangio (#6) | Brabham Cosworth | no time | 31 laps |

| 15. | Oscar Mauricio Franco (#40) | Tecno Cosworth | no time | 28 laps |

| 16. | Clay Regazzoni (#16) | Tecno Cosworth | no time | 27 laps |

| 17. | Ernesto Brambilla (#12) | Ferrari Dino | no time | 24 laps |

| 18. | Silvio Moser (#24) | Tecno Cosworth | no time | 15 laps |

| 19. | Carlo Facetti (#20) | Tecno Cosworth | no time | 6 laps |

| 20. | Carlos Marincovich (#42) | Tecno Cosworth | no time | 5 laps |

| 21. | Pedro Rodriguez (#38) | Tecno Cosworth | no time | 2 laps |

Even with the defeat in the last race of the season, the Ferrari team had already won enough points to give the Italian constructor the title even before the last race. Andrea de Adamich, who took two first places (in Cσrdoba and San Juan), as well as second place in the first race in Buenos Aires, had a large points lead over the driver in second place in the championship, Rindt, which gave the Italian some peace of mind, even with the seatback of the last race in mind. These two titles, now official, helped to scare away the ghost that haunted Ferrari in the double-race round of Buenos Aires.

The race 4 results in a nutshell.

And so ended the Argentine F2 season, already on the eve of the year 1969. Scuderia Ferrari surprised by its overwhelming performance compared to the other constructors and teams. Just a few weeks later, in the already consecrated 1969 Tasman Series (which was another European inter-season tournament), the Maranello team showed that victory in Argentina was not just due to luck but to the development of a winning car. Brabham emerged as a second force, while Lotus, Matra and Tecno followed close behind, as the main challengers on the European F2 circuit in the 1969 season.

Honoured were the Argentine drivers who were given the unique opportunity to challenge their European fellows. Even with the gigantic gap existing between these two worlds (as was demonstrated in the final standings of each race), many of the factors that prevented the drivers from Argentina from demonstrating their skills on track are not solely and exclusively the fault of this technical gap: see the amount of retirements due to mechanical failures (like Reutemann who had continuous engine problems throughout the season) and the amateurism of the Argentine federation which did not offer equal chances with the heavyweights from Europe.

Why read me?

It's no mystery to anyone that the sixties were one of the most colorful decades in F1 history. The years when amateurism took its last breaths, with the last victory of a privateer, when circuit safety began to become a topic of debate, when technology substantially changed the design of cars, in which drivers, with fewer commitments to their teams, could unfold their talents in other categories as many as they could, by the way.

One of the topics that those most passionate about those years always remember is the small inter-season of the European winter, where the journey of the European circus to the southern hemisphere happened as regularly as the migration of birds. First in Australia and New Zealand, then Africa; the invasion this time was not through the imposition of the sound of weapons, but rather, the sound of Cosworths and Climaxes. But a darker side of the obscurity that these championships were was the arrival of the European circus at the end of 1968 in Argentina, in what became known as the 'Temporada'. The country, which had once produced one of the greatest generations of drivers was now trying to reappear on the world stage in the best possible shape. And maybe it succeeded, at least in that exact year of 1968. Just take a quick look at the stellar grids that were formed in the four races that counted for the championship.

Therefore, it is not surprising that Argentine drivers desperately fought for a vacancy as an opportunity for an international career. Frank Williams signed for the duration of the season with Juan-Manuel Bordeu, who was one of Fangio's protιgιs and also one of the drivers who regularly participated in some of the numerous Formula Junior championships in Europe during the sixties, and Carlos Pairetti, champion at the time of the Turismo Carretera, one of the most important touring car championships in Latin America.

Ron Harris made an agreement with the state-owned YPF oil company to supply him with two other drivers to compose the team's roster during the season. Carlos Reutemann (who already had a victorious career in Argentine touring car racing) and Carlos Marincovich were chosen after going through a battery of qualifiers in a Brabham F3.

Andrea Vianini was another who managed to clinch a spot in the championship, getting a factory-new Tecno 68, mainly because of Pepsi-Cola sponsorship. Eduardo Copello and Jorge Cupeiro were others to get a cockpit.

But then, why is this championship now forgotten? Well, that's a rather difficult question that I won't even try to answer.