The 1958-'61 South American Triangular Tournaments

- Where front-engined Formula One went to die

Part 1: Introduction - A very peculiar championship

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- August 14, 2024

Related articles

- The 1958-'61 South American Triangular Tournaments - Where the front-engined F1 went to die, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1934-'37 Rio GPs - Postcards from Gavea, by Mario Cesar de Freitas Levy/Leif Snellman/Antonio Carlos Barque de Lima

- 1949 Brazilian Temporada - Brazil's forgotten racing days, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1950 Chilean GP - The first, the last and the only, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1966 Argentinian F3 Temporada - It's never too late to revive old passions, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1967 Argentinian F3 Temporada - Time to go south again!, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Argentinian F2 Temporada - The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas, by Lorenzo Baer

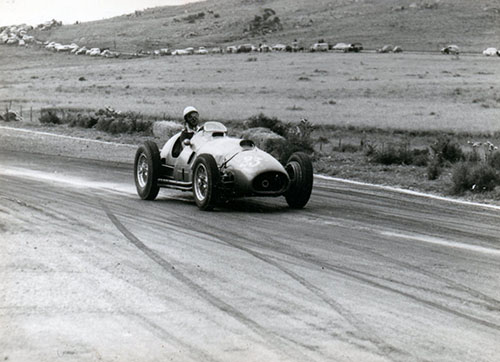

Who?José Froilán González What?Ferrari-Corvette 625 Where?Interlagos When?1958 Prefeito Adhemar de Barros Trophy |

|

Why?

In current Formula 1, the idea of a car surviving more than a year as an organic element of a team seems something inconceivable. With the accelerated developments within the category, the idea of a technological lag is constantly present in the minds of designers, mechanics and engineers, who have as one of their main concerns what the future could bring. The planning from the future starts in the present, and, to not stay behind in this technological race, innovation becomes the buzzword. So, a context of planned obsolescence is almost created, where the 1-year expiration date applies to a Formula 1 car.

However, history was not always like this. Going back in time, a few decades ago, F1 cars used to have a much longer, busy and peculiar lifespan, ending their careers far away from their original owners. The retirement of these machines within the great circus of Formula 1 only meant the beginning of another journey, where, for many more years, these former veterans of Spa or Nürburgring lived a life now in the shadows of their former glories. Many of these found their homes far south of the equator, where, almost in complete ostracism, the great representatives of an era took their last breath.

The reign of Maseratis and Alfas might have ended in Europe at the end of the 1950s, but in South America the supremacy of front-engined cars would continue for a few more years, before finally succumbing to the impetus of modernity. However, in their second life as racing cars, these vehicles would greatly enhance the history of Latin American motorsport, in one of its richest and also forgotten chapters. This is the history of the South American Triangular championships, an era in which F1's past and present converged, providing the last gasp of a golden era of motorsport.

South American motorsport: post-war and the 50s

Despite having started its rise in the 1930s, it was only after the Second World War that South American motorsport began to stand out on the international stage. Initially with the big event in the southern Atlantic – the Gávea GP, held in Brazil – and later expanding with the Argentine Temporadas and the GPs in Uruguay, the South American calendar offered a good range of events, spread across the three main countries in the South American motorsports cone. Because of this, it was not an uncommon sight to watch foreigners competing in these races, witnessing the increasing level of professionalism that permeated South American motorsport: Europeans could finally see that it was no longer about racing against a dozen of semi-pro drivers, with a composition of outdated cars.

Supported to a greater or lesser extent by their national motorsport federations (such as the Argentine ACA or the Brazilian ACB), these drivers originally from the Pampas or Tupiniquim lands became worthy opponents, competing in minimally frank terms in the international races that were held in their home soil. And, as increasingly competitive machinery became available to the South Americans, their results improved considerably, to the point where they finally demonstrated that they could surpass the hitherto unbeatable Europeans and North Americans.

It was at this point that the region's great leap forward in motorsport was made, when not only trophies and good prizes were on offer, but also a great level of competitiveness was included in this package. Drivers like 'Chico' Landi, Hermano da Silva Ramos, Juan Manuel Fangio, José Froilán González, Carlos Menditeguy and Eitel Cantoni raised Latin-American motorsport to a standard comparable to the one expected and promoted by the great European races, and that provided a moment of glory unconceivable few years back, outside the old traditional axis of motorsport.

It was through the big names that South American motorsport caught the attention of the public, demonstrating that a new order of peripheral countries on the globe could also contribute to the development of motorsport. Because of this, the 1950s can be considered the first glorious decade of South American drivers in the single-seater categories, with Argentinians and Brazilians, especially, winning the laurels previously reserved for their contemporaries from the northern hemisphere.

Oscar Mario González drives his Ferrari 375 at El Pinar in a Uruguayan Fuerza Libre event in 1958. González would own the car until the early 1960s, after which this Ferrari simply disappeared from the records.

(credits Jorge Sanguinetti)

Another important factor was that the visibility generated by these drivers in the international spectrum also reflected in the internal environment of these countries, with South American entities taking advantage of the success of their drivers to improve their methods and objectives. The truly national races, which were nothing more than luxury amateur events until the early fifties, began to be organised in more serious tones, as drivers had access to a more qualified infrastructure, close to that present on some European circuits.

Obviously, it is not a question of comparing a race at Petrópolis (one of the main venues of Brazilian motorsport, located in the mountainous region of RJ) with the ones in Spa-Francorchamps or Reims, but rather with races like Cadours or Chimay, which had a certain international status but were far from being the main stages of world motorsport. In comparison, many national single-seater races in Argentina enjoyed a structure similar (if not superior) to that of the temples of world motorsport, largely due to the interest of the Automóvil Club Argentino in leveling up with European national federations.

As already mentioned, the visibility of the drivers was also beneficial in the technological aspect of these championships, as Brazilian, Argentine and Uruguayan drivers now no longer had to be content with the 'leftovers' of Europe, having easier access to vehicles considered cutting-edge for the era. At the beginning of the fifties, countless Maseratis, Alfas and Ferraris, which were previously sold as scrap or to European drivers of dubious quality, found a second home in South America, being driven by some great stars of their time. This technological factor, combined with talent on the tracks, caused a boom within South American automobile federations, with national events multiplying as more top-rated drivers got their hands on more prepared vehicles.

Even though there was a great reduction in international interest regarding South American countries after the retirement of the tracks of their greatest exponents, in the second half of the 1950s, the process of national development and encouragement of motor sports in this region went forward anyway. Due to this and other political and economic factors, the federations of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay increasingly turned inward in the expectation that, in the future, they would once again regain their international spotlight.

In view of the need to reinvent themselves in these times of crisis, the three most important motorsport countries in the South of the Americas decided to come together, seeking to promote their own international Formula Championship: this is how the history of the Triangular begins.

A very peculiar championship

The idea of a unified South American championship dates to the end of the 1940s, when Argentina and Brazil each promoted their own automobile 'Temporada' under Formula Libre regulations. Composed of a series of races in each of these countries (in Argentina, four events were generally held and in Brazil only two), the 'Temporada' concept proved to be an immediate success, attracting worldwide attention as a mini-championship for F1-graded drivers during the winter months in the northern hemisphere. There was, during a fleeting moment in the early 1950s, an interest in unifying these two championships, but this project never got off the ground, mainly due to the failure of the Brazilian Temporada, which, from 1951 onwards, ceased to exist.

Because of this, the first embryo of the South American Triangular can be considered the year 1952 of the Argentine Temporada, when, in partnership with Uruguay, the Argentinians promoted another edition of their famous championship. The traditional four races that made up the championship were divided equally between the two countries, with the ACA promoting two events in Buenos Aires, while the ACU was responsible for organizing another two races on the recently opened El Pinar circuit.

The relationship between Argentines and Uruguayans narrowed throughout the 1950s (even more so after the loss of the Temporada's international status), with drivers from both countries crossing the River Plate to compete in races with their immediate neighbour. On the other hand, Brazil distanced itself from this relationship, due to a series of factors: the most important of them was the decommissioning of the very traditional Gávea circuit, in Rio de Janeiro, in 1954 – which, in itself, was a very hard blow to the ACB. Another point that worked against Brazil was the ever-present difficulties in transporting Brazilian drivers to Uruguay and Argentina, which was more due to inefficiency and the tight budget of Brazilian drivers than to any other logistical factor.

Because of this, little had been done to find a common point between the three countries until 1956, when the great watershed would be drawn in this history. That same year, there were significant changes to the structure of the Automovel Club do Brasil, the most important of which was the appointment of Ângelo Juliano to the position of director of the institution's State Sports Commission.

Juliano was a former racing driver, having driven FIAT, MG and Ferrari cars in several Brazilian events in the first half of the 1950s. Now, the veteran driver found himself in the delicate position of being the figurehead of the São Paulo branch of the ACB, which had become the most powerful in Brazil after the great loss of influence that its Rio de Janeiro counterpart had suffered in 1954. Juliano had inherited an adrift institution, which was urgently seeking a new identity to become internationally relevant again.

In addition to having as a primary objective the restructuring of motorsport in the state of São Paulo, Juliano had a more ambitious scheme to revive the idea of the South American tournament, which had been shelved since the beginning of the decade. Such plan, he thought, would serve both purposes, on the national and international spectrums. Because of this, it didn't take long for the new director to begin outlining the general lines of the resurrected project, alongside other more immediate objectives.

José Froilán González with the Corvette-engined Ferrari 625 during the Prefeito Adhemar de Barros Trophy, the first race of the South-American Triangular Tournament at Interlagos (1958). (credits unknown)

Firstly, seeking to strengthen the automobile scene in São Paulo, Ângelo bought and resold (throughout 1956 and '57) different types of Grand Prix cars, such as old Maserati 4CLT-48s or Alfa-Romeo 308s, at affordable prices to several paulista drivers. After years of continuous use, many of these cars showed significant signs of wear, the most worrying of which were related to the mechanical part of the machines. As a simple measure to remedy this problem, many of these vehicles were adapted to more modern, cheap and powerful engines, the preferred ones being the Corvette and Chevrolet V8. This gave these old cars a new life, which far exceeded that originally intended by their original builders.

With the cars finally available and distributed among the most promising Brazilian drivers, Ângelo took the first step in 1957, promoting a series of large-scale races in São Paulo – in particular, in the Interlagos circuit, which had already become the main mecca of Brazilian motorsport. Races such as the Mil Milhas Brasileiras, the Campeonato Paulista de Automobilismo and the 500 Quilômetros de São Paulo helped to substantially rebuild the image of motorsports not only in São Paulo, but also in Brazil as a whole. Perhaps the most important side effect was once again drawing attention to Brazil. This fitted perfectly into the plan outlined by Juliano, who now had a decisive hand in definitively integrating South American motorsport.

Due to this, between 1957 and 1958, the director of ACB paulista made a dozen trips to Uruguay and Argentina with the objective of opening negotiations with the institutions representing each country regarding the desire to finally create the South American integrated tournament. Both the ACA and AUVO (Asociación Uruguaya de Volantes, which represented the ACU in relation to motorsport events in Uruguay) were impressed with Ângelo Juliano's project, with the rapid process of restructuring Brazilian motorsport being a determining factor in the interest of both institutions.

After months of talks, the now named South American Triangular Tournament came to fruition at the end of 1958. The regulations, simple in their conception and accepted by all parties, defined that the championship would be composed of three legs, one in each country. Furthermore, each federation could have a maximum of three representatives in each race, who would score points towards the championship classification – any extra driver from these countries who registered for one of the races could not score points towards the standings, competing only for financial bonuses and trophies. The 'official' entrants for each nation should be defined in advance for each race, with replacement possible only with prior notice.

In the more mechanical aspect of the regulations, it was accepted by all parties that the formula of dispute would be what was called Mecânica Nacional which, due to the now more international tone of the championship, had become Mecânica Continental. But what this category was all about?

Mecânica Nacional: where the past and present meet

As mentioned in the previous paragraphs, many of the drivers who were due to compete in the planned championship would rely on ex-F1 vehicles, which regularly arrived in small batches in the South American countries after years of service in Europe. Many of these vehicles, running for official teams or privateers, had had the glory of participating in some of the most well-known and revered GPs in the world, having as battle scars the laurels they achieved with their original owners.

But, due to the rapid development of motorsport in the second half of the 1950s, many of these cars quickly began to become outdated. If, in the 1930s, a car from a large team could be used for two or even three seasons, it was already clear by the mid-fifties that one or two seasons became the maximum useful lifetime of a car in a high-end team. So, surplus cars which could still be considered competitive became more abundant and accessible on the market, satisfying the desire of many drivers whose great ambition was to one day drive a Formula 1 car.

Although they could be found at relatively competitive prices on the market, such vehicles most of the time proved to be real monetary traps for their new owners. Engines like the Ferraris and Alfa Romeos needed constant and meticulous attention so that they could perform to their full potential; and, despite the zeal of many of these new owners, issues such as a tight budget and lack of knowledge about such mechanisms ended up completely compromising the performance of these precise machines.

In response to this problem, many of the drivers chose, as soon as possible, to get rid of the original engines and replace them with other options, which presented a much more attractive cost-benefit ratio. This original idea had its roots in pre-war Argentine categories called Fuerza Libre and Fuerza Limitada, which used a mix of single-seater chassis (whether imported or locally produced) combined with modified American production engines.

Restructured after the conflict, both Fuerza Libre and Limitada resumed their positions as the main Argentine and Uruguayan national categories in the 1950s. The first important step in the history of Fuerza Libre races in this post-war phase was the one taken by Asdrúbal 'Pocho' Bayardo in mid-1956, credited as the first driver to combine an F1 chassis with a V8 in South America. The Uruguayan's car of choice was an old Maserati 4CLT-48, which had its original engine replaced by a tuned Chevrolet V8. 'Pocho' didn't take long to start collecting victories with the 'new' car, and, consequently, the idea became widespread throughout the Rio de la Plata basin.

Asdrúbal Bayardo was the pioneer of MN/F Libre in Latin America. After executing his idea of combining an American V8 engine with an F1 chassis, the circuits in South America would never be the same. (credits Jorge Sanguinetti)

Later on the decade, Brazil also adopted this type of formula, which became known as Mecânica Nacional locally. The abundant number of ex-F1 cars was indispensable in the Fuerza Libre/Mecânica Nacional expansion process, as such vehicles were indisputably superior to any car that could be manufactured locally in these countries. Most of the vehicles that would compete in the South American Triangular Tournament, at the end of 1958 had an average age of 5-6 years, coming from the most diverse manufacturers and specifications: Ferraris of the types 125, 375, 500 and 625, Maserati 4CLTs, Alfa 308s, Gordini T15s and even a Talbot T26C would join a contingent of modified sportscars, which would race throughout the three stages of the tri-national championship.

As the powerplants of choice, most of the vehicles were equipped with American engines, as had already happened in the Argentine and Uruguayan categories. The most desired of these devices was undoubtedly the Corvette V8, in the 4.3-litre (1956) and 4.6-litre (1957) versions. As they required few modifications to become competitive racing engines, Corvettes were imported by the dozens for the South American racers.

Added to the equation was the fact that these were engines that were quick to repair, easy to maintain and would offer a surprising increase in performance compared to the old Ferrari and Maserati. Other Chevrolet engines were also favoured by drivers, especially in the 4.6-litre versions, which were enlarged and modified until they became real racing-spec powerplants, transforming the already skittish F1 cars into extremely difficult machines to tame. For example, there are records of Chevrolet engines that raced in the Fuerza Libre with the Wayne package (produced in the USA by engineers Wayne Horning and Harry Warner), which increased the horsepower of the V8s with an ingenious 'twelve port' cylinder, substantially improving the compression rate inside the engine.

In addition to these, other American V8s also found their acceptance among the less fortunate on the grid: Ford, Plymouth, Chrysler and Studebaker proved to be more affordable choices, with each one having its own weaknesses, but also its virtues – which were often exploited to the maximum by the creative South American tuners. Other more peculiar options that found a way to Fuerza Libre/Mecânica Nacional at one time or another were Porsche and MG, which had short-lived stints in the category.

Thus, the first season of Mecânica Nacional/Continental represented the union between the past and the present of motorsport: seven-year-old chassis, equipped with newly manufactured engines! It was time to test in practice whether the dream of the South American championship really deserved to flourish.