Ferrari at Indianapolis: mutual love unanswered

1952: Ferrari at Indianapolis

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- December 5, 2012

Related articles

- March-Porsche 90P - The last oddball at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, by Henri Greuter

- March-Alfa Romeo 90CA - Fiasco Italo-Brittanico, by Henri Greuter

- The Race of Two Worlds - The 1958 "Monzanapolis" bash, by Darren Galpin

- Ferrari at Indianapolis, by Henri Greuter

- 1951: Ferrari and Indianapolis

- 1956: A 'hybrid' against one of Indy's most persistent jinxes

- 1958: At home against Indycars

- 1961-1968: Of phantoms and enfants terribles

- 1971-1973: 'Meet my uncle Franco'

- 1975: A loud insect never leaving the chrysalis as was intended and hoped for…

- Intermezzo: Ferrari and turbocharging

- 1986: Projects 034 and 637, mere blackmail tools?

- 2000-2007: It's Indy, Gino, but not as we know it

- Appendix: The cars

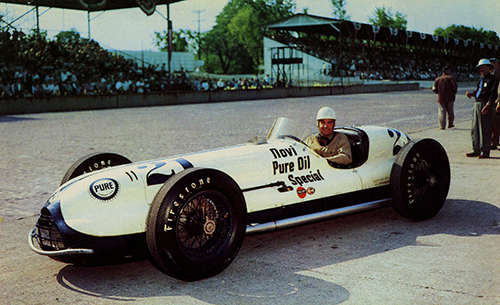

Who?Alberto Ascari What?Ferrari 375 Where?Indianapolis When?1952 Indy 500 (photo First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission) |

|

Why?

A number of interesting developments were taking place early 1952 in the build-up to the race. The Cummins company developed an even more optimized version of their 6.6-litre straight-6 engine suitable for racing at Indy, this one being turbocharged. It was modified to become part of an entire package, with a chassis designed around it. A radical new 'Indy Special' was on its way.

Elsewhere, the capabilities of a supercharged Offy engine were still regarded promising and its developmental efforts were continued by a team guided by an experienced mechanic, Herb Porter. This time the centrifugal blower was replaced for a Roots blower since this type was known to provide more power and torque at lower rpms, making the car more drivable. Raw power was less in comparison with the centrifugal blower but decent acceleration was of more importance at Indy.

Also elsewhere, in the team of millionaire Howard Keck, chief mechanics Jim Travers and Frank Coon concluded that the heydays of front-wheel drive were over. Theirs had been one of the few teams who had followed the concepts and strategies of Lou Moore and fielded a car similar to the nearly invincible Moore-inspired Blue Crowns. They even used a key part of what once was Moore's package. Right after the 1949 race Moore fired Mauri Rose in his anger about Rose's refusal to accept second place behind his team mate, instead going for personal glory. Moore could have ended up with his three cars in first, second and fourth place, cashing the corresponding prize money. Rose's quest for personal glory caused Moore to end up with first, third and thirteenth place instead. When Rose complained to Moore about how the car had broken down on him an argument followed which ended with Moore firing Rose on the spot. Rose was utterly cool about it, which may be proven by the fact that when he left the track one of the first things he did was going to check Duke Nalon's situation, whom he had seen crashing his Novi in one of the most fiery crashes ever at Indy.

Rose was hired by the Keck team from 1950 on. He scored a third place in 1950 and retired after an accident in 1951, having been classified 14th. 1951 had seen no less than six front-wheel drive cars qualifying for the race, all of them built after the war. 1951 definitely wasn't the year with the most FWD cars in the race (that was 1947) but it was the year with the most post-war-built FWD cars in the race ever. However, the race results told a tale for the future if one took a better look at the situation. With hindsight, the upcoming developments were clearer but only a few people saw it coming.

Travers and Coon realized they needed a replacement for their front-wheel drive car. They were lucky their boss Howard Keck had unlimited faith in them, so they got a free hand. One option Keck went for was fairly remarkable, but he wasn't the only one.

Luigi Chinetti did a great job. Ferrari intended to field two factory-supported cars but Chinetti managed to interest three American customers in buying a 375 for Indianapolis. One of the customers was Gerry Grant and his partner John Bartlett. Grant came to Italy in the winter of 1951-'52, accompanied by driver Johnnie Parsons. Multi-millionaire Howard Keck provided his mechanics Jim Travers and Frank Coon with two new cars. One of them was a Ferrari 375.

Ferrari's intentions of entering the '500' first appeared in print on March 18. Some believed the first places in the upcoming race were now spoken for. A number of magazines paid attention to Ferrari and the cars it intended to field, raising interest and lifting the expectations for the Italian thoroughbreds. Many insiders were impressed with the Ferrari and its awesome specifications.

According to the records, Ferrari prepared five of the 375 F1 cars during the winter and spring of 1952. The running gear of the cars was put into new, strengthened chassis which had their wheelbase slightly lengthened compared with the original cars. It has been published that new, strengthened frames were built to put all running gear onto but this is not 100% sure. The actual wheelbases of the cars that survived have been measured in the past and all of them differed a bit. The approximate, average value for the wheelbase is given as 242 mm.

Three of the cars were entered for the Valentino Park GP in Turin on April 6. One of them was driven by Nino Farina who crashed it. The car couldn't be repaired in time to be sent to Indy. Ascari drove another car, leading much of the race until the fuel tank split, with Gigi Villoresi in the third car eventually ending up winning the race.

The first of the cars to arrive at the Speedway was the Grant Piston Ring entry, a car painted white, with red trim, numbered 6, to be driven by Johnnie Parsons, who had won the rain-shortened (345 miles) 1950 race. This car stood out from the other 375s that appeared at the Speedway because of its wrap-around plexiglass windshield instead of the single windscreen. The car was registered as chassis 2 and powered by engine 02. After its arrival in the USA the car had been sent to Frankie Del Roy's shop in East Paterson (New Jersey) where Del Roy, assisted by George Ellis and Danny Eames, had prepared the car for the upcoming race.

As already mentioned, millionaire Howard Keck had bought a Ferrari 375 which was looked after by his top mechanics Jim Travers and Frank Coon. Frank Coon was send to Italy in order to have a look at the car on site at Italy and learn how to maintain it. He arrived on April 12, saw to it that the car was shipped to New York by boat and flew back to the USA on May 3. Travers and Coon had put the engine of their car onto a dynometer and found out that the V12 produced good enough top-end power. Nevertheless, Jim Travers had his reservations about the Ferrari and he focused on the other car in the Keck team. Travers had gone as far as describing the Ferrari as "a mess" and he didn't wanted to bring it to the Speedway. But the Keck car did show up after all, painted light blue with red trim and numbered 38. The chassis number of this car was 4, its engine has been reported as having markings of a 5 on the block but a 4 elsewhere. It arrived at the Speedway on Sunday May 11, although it had no driver assigned yet. Bill Vukovich, entered for the other car in the team, took it out for some laps but stuck to what he was assigned to. Eventually the Ferrari ride went to Bobby Ball.

The third customer 375 had ended up with Johnny Mauro, a driver who had gained more of a reputation at the Pikes Peak hillclimb then at Indy. For fans of Italian-built racing cars, Mauro was a known name since in 1948 he had driven what until that moment had been the last Alfa Romeo to ever race at Indy. The car was no longer fast enough in 1949 and Mauro failed to qualify yet again. It has been mentioned that Mauro primarily bought the car to use it at Pikes Peak and that driving it at Indy was more showing off than a serious attempt at making the field.

Alfa Romeo debuted at Indy in 1990 with a factory-supported team. Their track performance was far from impressive but their PR was fantastic. Between Bump Day and Carb Day they organized a press conference with Roberto Guerrero and the man who was the last driver ever to race an Alfa in the “500”. Johnny Mauro entertained everyone with his stories about his last outing with an Alfa in 1948. (photo HG)

Mauro had obtained some last-minute sponsorship and his car, numbered 35, was entered as the Kennedy Tank Special. The car was painted white and had blue numbers with a red trim. The chassis number of this car is unknown although it is believed to be 3. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that the engine number is also known as 3.

Ferrari 375s were either red, or in the case of the Thinwall Special green. Seeing a 375 in any other color means you are looking at one of the cars that was at Indy in 1952. This is how Johnny Mauro's pride and joy looked. If its achievements made Mauro proud remains to be seen. (photo First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

And then there was the factory entry. The driver Ferrari entered was Alberto Ascari, one of the heroes who in the year before had helped to end the reign of the near invincible Alfetta 158 and had almost won the world drivers title.

The Ferrari was entered as number 12, colored red with white trim. According to investigations, this car was numbered 1 among the 375s and had engine 1 or 01. The car differed from the other three in apparently having a longer wheelbase: a reported 100 inch or 2540mm. The car arrived in the first week of practice (Thursday May 8 is given as the date) and was subsequently prepared for the race by two Italian mechanics. Ascari meanwhile dealt with the local press, assisted by Tino Martinoli (sent by Ferrari) and a local man, John Cuccio. The latter was assigned to the team by the Speedway management and worked as a translator. Ascari started his rookie test with the car on Sunday May 11. Due to rain he was only able to finish this mandatory test on Tuesday May 13. He impressed many with his patience and skills. But then the hard work began: in the following days the track was plagued by lots of rain, leaving little opportunity to drive. However, during the laps that Ascari did do it was apparent that there was a big problem.

The factory-supported Ferrari shared the misery that also befell the customer cars: it simply wasn't fast enough. Ferrari provided additional support by sending over a crew of mechanics, accompanied by none other than engine wizard Aurelio Lampredi. The car was fitted with three double-choke Weber carburettors and the men made a phone call to Italy with the request to airfreight a new manifold with three four-choke carbs, which duly arrived. It required modifications to the car's bonnet to install them. Needless to say, that work was carried out as well.

None of the Ferraris tried to qualify during the first weekend of qualifying. So the stage was left to another car to steal the show. Whatever humiliating comments Enzo Ferrari may have had in mind (and had actually said!) about the Offenhauser, it would be interesting to know his thoughts about the engine in the car that qualified fastest on Pole Day. Much to anyone's surprise, the pole sitter would be Freddie Agabashian driving the turbocharged Cummins Diesel entry. By far the heaviest car entered, it had actually worn down its four tyres to the canvas during its qualifying attempt but it was fast! So a hopped-up truck engine had taken the pole at Indy.

Should there ever be made a shortlist of the ten most innovative and significant Indycars, this car most definitely would make the list. Not because of its successes but for being a pioneer of technologies that would be successful only years later. Freddie Agabashian in the revolutionary Kurtis-Cummins Turbodiesel, a significant racing car in motor racing history, perhaps not for the immediate future of Indy but certainly for its long-term future. (photo copyright IMS Photos)

For Indy standards it had been a remarkable weekend, since a mere seven cars made a qualifying attempt on the Saturday known as Pole Day. When the following day rained out again the first weekend ended with 26 spots left for grasp.

Travers and Coon came with an interesting modification to their 375 right after that first weekend of qualifying. One of their partners they worked closely with was Stuart Hilborn, who had built a fuel injection system suitable for the Offy racing engine, so Travers and Coon had their 375 engine fitted with this system. It fitted nicely within the V and for a modification on the spot it looked very good. The fuel injection worked fairly well on the engine. Driver Bobby Ball managed to do a lap with an 134.4mph average. If Ball could manage such a speed in qualifying he would qualify for the race. But despite the fact that the Keck entry was faster in practice than the factory car, Keck eventually withdrew the car from the event. He did so on request of his mechanics Travers and Coon in order for them to focus their efforts on the team's other car. We'll get to that car later on. Travers has stated that Keck was rather annoyed about the withdrawal of his valuable Italian thoroughbred but his mechanics at the track simply had no faith in the car. They wanted to concentrate on their second car. And if that wasn't enough, driver Bobby Ball made it clear that he didn't like the Ferrari. Luckily for him, he wasn't without a ride after the Ferrari's withdrawal, as he moved over to the #55 Ansted Rotary Engineering Special, an Offy-powered Stevens chassis.

The factory team also changed the fuel supply on their car that weekend. They installed a new inlet manifold with three four-choke carbs on the engine to replace the three dual-choke Webers. The manner in which the team obtained the manifold is a story in itself.

Italy's prime motor journalist Giovanni Canestrini hadn't bothered to go to Indianapolis but on his return from England his wife waited for him on Milan airport with a another packed suitcase so he could instantly fly to Indianapolis instead of coming home! He made the journey with Aurelio Lampredi and Ferrari's team manager Nello Ugolini. Disaster struck once the threesome arrived at Indy and discovered that the manifold they were supposed to bring along accidentally had been sent off to St. Louis instead! Fortunately for the Italians, the package was delivered a few hours later and the next day the carbs were installed on the engine. But the entire system was taller than the original carbs and the bonnet of the car didn't fit properly. This proved the least of the problems and was eventually taken care of.

The thought came up in the team to ask Bill Quinn if he was willing to talk with race director Wilbur Shaw about allowing Ascari to start the race anyway, without the need to qualify. Quinn refused to do so since he knew that Shaw would never go along with such a proposal. Using promoter's options to fill the field or add to it had never been an issue for the Speedway. Even as late as in 1947 when after a lot of political turmoil only 30 cars had qualified there was room for three more cars to be added to the field. It didn't happen.

With the second and last weekend of qualifying coming up rapidly, the pressure in the factory team grew, as well as that between the Grant team and the factory team. The Grant team felt that they got too little support by Ferrari. The problem for them was that they had more than enough to deal with, since their own car wasn't fast enough either. In return, the factory team was upset about the Grant team using Halibrand magnesium wheels. According to the factory that upset the settings of the car.

A white elephant at Indy, the Grant Piston Ring Ferrari, much fancied but depite all efforts a non-starter at Indy in 1952. (photo First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

Parsons had never got the car over 132.5mph, despite all his efforts. Parsons eventually gave up on the Ferrari, even declining his team owner's offer for a substantial amount of money to qualify the Ferrari. During the last weekend of qualifying Parsons moved over to Jim Robbins's team which fielded a Kurtis-Offy. Of all cars available, this was the exact car with which he had finished second in 1949 and won in 1950. He qualified the car 31st but finished 10th. Driver incapability was definitely not the reason for Parsons failing to qualify the Ferrari.

There are stories saying that Parsons was considered for a 1953 drive with the Ferrari team in Europe but that deal was also off.

The #6 Grant entry was also tried by Walt Faulkner. Walt was definitely not a veteran driver with many years of experience under his belt, since 1952 was only his third year at the Speedway. Nevertheless, if anyone had the right to say if a car was good or wasn't, Faulkner was one of them. He had burst onto the Indy scene in 1950, his rookie year, and truly stunned everyone when he qualified on pole with the fastest 1- and 4-lap average. But if that wasn't enough, he broke the qualifying records set by the late Ralph Hepburn in 1946 with the powerful front-wheel drive Novi, generally accepted as by far the fastest car at the Speedway. One year later it was Novi driver Duke Nalon who showed the speed of the Novi by reclaiming the track records when he qualified on the pole. Faulkner wasn't ready to defend his record but one week later he was and won the qualifying records back again, even though it brought him only the 14th starting spot. Despite the speeds he showed in practice, his team owner in those years (the legendary JC Agajanian) had fired him for 1952 so he was available. Faulkner took the drive in the Grant Ferrari but didn't like it for one bit. Faulkner has been cited as having said “So this is the great Ferrari?” followed by some undisclosed comments in which Faulkner made it clear that the car would be better off when sent back to Italy. To add insult to injury, Faulker made comments to Parsons expressing that he felt sorry for Johnnie to have ended up in the Ferrari.

Then Ferrari mechanics Antonio Reggiani and Stefano Meazza found another tweak in order to improve the Ferrari's speed when they put 3-inch velocity stacks on top of the carburettors. That proved to be good for a speed increase of some 3mph.

The only 'all red' Ferrari at the track, its number appropriate given the number of cylinders in the engine. The only one of the much fancied Ferraris that made it into the race after lots of work.

(photo First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

During the final weekend of qualifying Ascari managed to qualify the Ferrari late in the Saturday afternoon with a speed of 134.308mph. Once qualifying was over and done with, Ascari occupied the 19th starting spot, inside of row seven. Due to Indy's peculiar qualifying system in which drivers are ranked according to their qualifying day and only then according to speed, it could happen that the fastest qualifier didn't start on the first row but on the next-to-last row. Chet Miller, driving one of the heralded Novis, was the last driver to make the field on Monday May 26. Rain had made qualifying impossible on Sunday May 25 and the day had ended with two starting spots still open. Since there were still so many eligible cars left that were able to make the field it was no option to nominate two lucky drivers. And so qualifying was extended for another day. Miller made the field in a rather unusual manner. That Saturday May 25 he had made a qualifying attempt in which he first broke the one-lap qualifying record and then broke his engine. A wrecked piston was discovered and the Novi team ordered a piston that would be air-freighted out of their home base in California. Two days later Miller made another qualifying attempt late in the afternoon and this time he finished his qualifying attempt with a new record over four laps. The new record notwithstanding, he still ended up on the 27th starting spot. Had the starting field been ranked according to qualifying speed Chet would have been on pole while Ascari would have been 25th. Another curious situation was that Miller stood on the outside of row 9, while left of him on the 26th spot was Jim Rigsby, the slowest qualifier that year! This was the only occasion in the history of the “500” that the slowest and fastest driver in the field were lined up next to each other.

The IMS Photo Shop cooperated in the release of postcards featuring qualified cars. This postcard is showing the 1952 qualifying picture of Chet Miller, fastest qualifier with new track records. It was to be Chet's last-ever race at the Speedway. One year later, driving this very same Novi, he was killed in a crash on the Friday before Pole Day. (photo copyright IMS Photos)

Bobby Ball had qualified the #55 Ansted two places ahead of Ascari, in 17th place. Walt Faulkner had the misery to lose his track records but he also failed to qualify for the race.

Ascari's qualifying performance, however, became one for the record books nonetheless. Perhaps the speed itself wasn't a record, Ascari's consistency was. The time difference between his fastest and slowest laps was a mere 0.08 seconds. His third and fourth laps were identical. Historically, Indianapolis never cares so much for lap times since the focus has always been on average speed. Ascari's lap speeds were listed as 134.208, 134.368, and 134.328 for the third and fourth lap. It certainly proved that Ascari managed to get the most out of his car during his entire qualifying attempt and that there wasn't much speed left in the car.

It has been often mentioned that in order to remain fast enough, Ascari was actually using the gearbox of his car, shifting down a gear for the corners and back into top gear on the straights. But according to team member John Cuccio this wasn't the case at all. Only on one practice day the car was tried with a higher final-drive ratio forcing Ascari to shift on the track. Since it didn't gain him any advantage the original final-drive ratio was installed back again.

Danny Oakes tried to qualify the #6 Grant car on that last day of qualifying. He started the attempt with less than 10 minutes to go before qualifying ended. Since he was too slow he aborted the attempt. The #35 Kennedy Tank and the #38 Keck car never appeared in the qualifying line for an attempt. In practice and qualifying the Ferraris certainly had proven to be a failure. Somehow, Oakes had impressed Ascari enough to nominate him as his relief driver.

Ascari qualified for the race after many hard efforts, but for the race itself prospects were better. A number of cars had qualified using fuel injection on their Offy engines since this gave more power at the expense of higher fuel consumption. No problem for qualifying but for the race it was a different matter. Several teams replaced the fuel injection for carburettors to be used in the race. Another power-enhancing trick used by many teams was doping the fuel with 'pop', or nitromethane. Even though this enhanced the power output, the technique was unsuitable for the race since it also raised fuel consumption figures. None of those tricks had been carried out on the Ferrari #12. It was qualified in a trim that came much closer to its race specification than that of its opposition.

Ascari's race strategy was to keep the revs below 6400rpm, resulting in laps averaging 128mph. Two pit stops for fuel and tyres were planned.

In contemporary race reports Ascari and the Ferrari were rated as fearsome competitors in the actual race, despite the fact that the Ferrari was acknowledged to lack torque. This would give the Offy-powered opposition an opportunity to overtake Ascari out of the turns, purely on acceleration. However, Ascari proved to be a quick student and on his 22nd lap he performed a high-speed pass on several cars in a single move that was noted by many and earned him tons of respect with the onlooking railbirds. Eventually Ascari ran as high as 8th but after 40 laps, while in 12th place, it all went wrong. Ascari spun off in Turn Three, didn't hit anything but came to a standstill. Then the Ferrari was carried off the track by wrecker crew. Ascari tried to prevent this and make it back to the pits but his inability to speak English made it impossible for him to explain his intentions to the track workers.

Ascari's retirement was described as follows in a 1952 race report.

The right rear-wheel bearing had frozen and due to its regular rear axle, thus being fitted with a differential, the car spun, made a complete revolution and came to a standstill on the grass. The wild gyration had caused the wire spokes to be torn off from the right rear wheel, leading to the retirement of the car.

Other publications state that that the rear wheel simply collapsed, most likely caused by the stress of the high-speed left-turn-only character of the track.

Ascari was eventually classified 31rd. There are publications which state that Ascari could have won the race and that the Italians were convinced they had a decent chance actually do well in the race. The matter remains, however, that the car had been less than convincing in practice. It was perhaps true that Ascari had qualified in a setup closer to what he was going to use in the race, compared to his opponents. If the mechanical failure hadn't occurred, who knows what might have been possible, purely on reliability?

The Ferrari impressed few railbirds, but the same can't be said of its driver. Ascari impressed many onlookers and despite his inability to speak decent English, he was well liked by many at the Speedway.

Bobby Ball was even less fortunate than Ascari. His race was over after 36 laps and he was classified one place below Ascari.

Ferrari hadn't brought a technical revolution to the Speedway. Nevertheless, the year 1952 is remembered as a year of major technical revolution at Indy. Two cars were responsible for this. One of them was two steps too far too early. The pole-sitting Cummins Turbo Diesel of Freddie Agabashian could not follow the leaders' pace but acquitted itself decently. Regrettably the car had one design flaw: the turbocharger's inlet sat at the front and after 76 laps the car had to be retired because the turbocharger had clogged up. It would take a few years before its tilted engine concept would re-appear at the Speedway. It would take even more time before the turbocharger re-appeared at the Speedway. The Cummins Turbo, however, was the first to use these technologies. They would later make a name for themselves, first at Indianapolis and later on, especially with regards to the turbocharger, in other types of racing.

The second car to revolutionize Indy that year was the car which made Jim Travers and Frank Coon so disinterested to work with Howard Keck's Ferrari. Together with chassis builder Frank Kurtis they had created a new, experimental car in which they tried some of their ideas. It took some time for them and their driver to understand the car and make it work, but once it did they didn't even consider trying to make the Ferrari work. A justified decision: the car in question was the Kurtis-Offy KK500, entered as the #26 Fuel Injection Special. The KK500 was the first of the so-called “roadsters”, the most charismatic of Indycars to appear at the Speedway. Roadsters typically had their (Offy) engine in the left side of the frame, with the cockpit to the right, the driver sitting next to the driveline. The concept worked fantastically once Travers, Coon and driver Bill Vukovich had worked out how to set up the car. In the race Vukovich laid down a dominating performance and led most of the race. He would have won the race if the car hadn't developed a steering problem causing Vukovich to crash with eight laps to go. But Travers, Coon and Vukovich had shown the future to Indy.

The most significant new car of 1952 that was to revolutionize Indy in the upcoming decade. Vukovich drove this car from 1952 until 1954. He almost won 1952 and did win in 1953 and 1954. The car was retired in 1955, and after tragic circumstances was refurbished in the 1953 colors and donated to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum.

(photo HG)

Vukovich's misfortune enabled a big Ferrari enemy to win the biggest race of his career up until then. Troy Ruttman, driving the #98 Agajanian Special with chief mechanic Clay Smith, had the pleasure to win the race, Ruttman becoming the youngest ever winner of the “500”. Ruttman definitely didn't drive the best car in the field, that had been Vuky's KK500. But as with the Carrera Panamericana, Clay Smith had prepared the car he had to work with in the best possible way, giving Ruttman a competitive drive, enabling to pounce if the best cars in the field would fail. Ruttman's average over the distance was 128.922mph, a speed little more than the speed range of Ascari's race strategy. In how much has this fuelled the idea that Ascari could have won the race?

A car typical for the very early fifties. Rear-wheel drive, Offy-powered, suitable for the rough dirt tracks and capable of holding its own at the Speedway: Troy Ruttman's Agajanian Special, winning car of the 1952 Indy 500, the last ever of the dirt car-style cars to win at the Speedway. (photo Mike George, used with permission)

Looking back in Indy history, 1952 became a memorable year. Of all the years that made up the fifties, it had the most technical variety regarding engines and chassis technology, and it was a year with firsts and lasts for a number of principles and concepts.

Why the Ferrari 375 had failed to make a decent impression at Indy was fairly easy to understand. The power output of the engine was comparable to that of the Offies, the primary opposition to deal with. The V12 gave away at least 100hp on the supercharged Novi V8 but the Novi needed much more (methanol-based) fuel than the Ferrari. In its days the Novi was rated as a favourite to win the race but with hindsight it was anything but that. Even if mechanical troubles would stay away (a thing that rarely happened to Novis…) it still was an outsider at best.

The downfall for the 375s was the lack of torque their engine produced. This prevented a decent acceleration out of the corners and onto the straights. The Ferraris did reach top speeds comparable to their average opponents but it took more time to reach that speed and they had less time to run at top speed before the next corner came up. The Offy four-banger, long-stroke as it was, perhaps revved much slower than the Ferrari but already at low rpms it produced levels of torque that enabled a tremendous acceleration out of the corners. The Ferraris were beaten getting out of the corners. Power was important to reach high top speeds but torque was just as important. In fact, Meyer & Drake, the builders of the Offenhauser engine, had found out that lesson themselves. Their 1951 experiments with a 3-litre centrifugally supercharged Offy were deemed a failure because although the block delivered some 50 to 60 more hp the drivers using the engine complained about the lack of torque and acceleration. For 1952 the factory had built up a 3-litre Offy with Roots blower instead but the blower broke down during a test so the team that was to use the engine had no other option than to use a centrifugal supercharger again. Driver Andy Linden did a good job with it, qualifying second fastest on Pole Day. He was, however, the first retirement in the race.

In the July edition of Road & Track magazine, the following comparisons were published about the Ferrari V12 and Offenhauser Straight 4.

| Ferrari V12 | Offy | |

| Bore | 80.0mm | 109.5mm |

| Stroke | 74.7mm | 117.5mm |

| Approx. hp | 380 | 325 |

| Peak power rpm | 7500 | 5500 |

| Piston speed | 3565ft/min | 4000ft/min |

The Offy's power output, in particular during practice, could be somewhat higher when using fuel injection and nitromethane fuel. At first sight the Ferrari values look much better and promising. However, the one figure not listed in this stat (torque) was the decisive factor in their practical use. Enzo Ferrari may have made downright insulting comments about the Offy, using words related to some kind of agricultural vehicle about it, the Offy had humiliated his thoroughbreds.

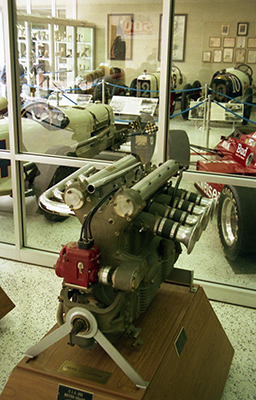

A 270 Offy engine with fuel injection. In 1952, the Offy ran on carburettors in race conditions most of the time. Big, high, not exactly light and with maintenance rather complicated because of its integral cylinder head. But other than that: simple and all you needed at Indy in the fifties. (photo HG)

Other setbacks for the car were related to its road-racing backgrounds. Road racing required multiple gears while at Indy the tremendous torque of the Offy enabled cars with this engine to be fitted with a two-speed gearbox that was much lighter than the Ferrari five-speed. Road racing also required better and larger brakes compared to Indy, which was yet another massive difference in weight. So the 375 had a weight handicap due to its road-racing heritage, and the additional weight had its effects on both cornering speeds as well as acceleration.

Thus, Ferrari's first Indy adventure ended in a rather subdued manner, with some moments of embarrassment. Interestingly enough, the July edition (post-race) of Road & Track was rather positive about the Ferrari, as well as the influence the magazine had had in bringing more technical variety and interesting new developments to the Speedway. Was this justified?

In one respect, however, Enzo could be pleased. With three cars of his cars sold on the spot, he was relieved of some redundant hardware and got at least some money for them in return. There is talk about each of the three cars having been sold for $30.000 each. Jim Travers suggested that Howard Keck paid some $58.000 for his car! Even if it was $30.000 each, then Ferrari had done tremendously well for cars that, frankly spoken, achieved so little, because with only a single car qualifying from the four of which so much was expected one cannot be very positive about their Indy careers. Now perhaps a second car could have qualified if Travers & Coon had been more committed to the Ferrari but they weren't, and with the benefit of hindsight that was more than justified given the other car they had in their team.

So did it make sense for Ferrari to try again one year later, using the experience gained in 1952 to improve the cars?

There were certainly a couple of easy remedies, wheels and rims for example. That is if the Italians were man enough to realize that the wire wheels they used weren't up to the job. The #6 Grant car had been tried on Halibrand magnesium wheels but the failure of that car to reach qualifying speeds was blamed by Ferrari factory members to the use of these wheels!

Much work was required on engine performance. Any power advantage of the V12 over the Offy (if there was such an advantage to begin with) had proven of little value. The lack of torque had to be compensated in order to improve the car's acceleration. And what kind of major engine rebuild would that have taken? The easiest solution on paper would have been to reduce the bore and lengthen the stroke to remain a 4.5-litre. But firstly, did the construction of the V12 offer such possibilities? And secondly, was this possible against reasonable costs?

A simple return to the Speedway with the cars as they had been in 1952 made little sense.

375 follow-ups

The disappointing 1952 adventure didn't fully wipe Indy from Enzo's mind but the plan for taking part in 1953 was simply started too late to stand a chance. The 1953 car was supposed to have a 3-litre supercharged V12 engine. Like the 4.5-litre it had two valves and a single overhead camshaft on each row of cylinders but eventually this car, to be driven by Alberto Ascari, wasn't ready in time and the entry was withdrawn. It says something about the impression that Ascari had made the year before that he was offered a drive by an American car owner (Ernie Ruiz) instead. Ascari had to turn down the invitation.

What is believed to be the chassis for this 1953 project was a chassis numbered 0388. This was based on an undisclosed 375 chassis, according to several publications most likely being the Ascari car of 1952. Reports say that the intended 3-litre engine (with a bore and stroke of 68mm each) was tested on the bench as late as September 1953 and was rated with an impressive 505hp. Track testing followed but the project came to an end when the engine blew. Other reports tell that the engine was never fitted to the car since it blew. The engine in question has been referred to in Ferrari literature as the 250/Nautico which suggests that it was being developed for use in some kind of boat. Whatever the plans might have been, it wasn't available for any use anymore.

So the intended Indycar 0388 was fitted with a 4.5-litre V12 engine instead and sold to Luigi Chinetti in early 1954.

Johnny Mauro had entered his Ferrari for the 1953 Indy 500 again. It appeared in the entry list under number #47 but the car never arrived at the Speedway.

A 375 was entered in 1954 for Luigi Chinetti, in the name of his wife Marion. It is near certain that the entry was made for this particular car, chassis 0338. It was numbered 47 and named Ferrari Special. The car used Borrani wire wheels with forged center sections and had a four-speed gearbox. Bore and stroke for the engine have been listed as 3.30 by 2.67 inch (83.8x67.8mm). This would mean that the engine was even less long-stroke than the 1952 cars were. What effect would this have on the engine torque?

1954: a new year, and new chances for Ferrari? (photo copyright Bob Mount Pictures, courtesy First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

Some sponsorship came from American magazine Car Live. The car was a late arrival, however, appearing only a few days before the last day of qualifying. It looked horrible, specially when compared to the new hot cars at Indy, the roadsters. The bonnet had a big air scoop, reminiscent to the one on Ascari's car two years before while large bulges had appeared on the sides in between the wheels. The driver sat very high in the car compared to the drivers in a roadster.

All elegance that the 375s once had was gone in this Indy version. (photo copyright Bob Mount Pictures, courtesy First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

At first sight the car simply looked out of place and outdated compared to its American-built opponents.

The story is told that the car was scheduled to be driven by Gigi Villoresi, but he never arrived at Indy.

It remains the question how much 0388 was mechanically different from the cars that ran at the Speedway in 1952, other than the aforementioned details. In general it appears as if the car was nearly identical to 1952 specs, making its competitiveness very doubtful. Only one of the four cars had barely qualified in 1952, and that wasn't without last-minute modifications. More seriously, thanks to the arrival of the Indy roadster much of the opposition had faster cars, since during 1953 and early 1954 Frank Kurtis had sold a fair number of cars based on the 1952 car he had built for Travers & Coon. The Offy roadsters reached high 130 averages, while reportedly the Ferrari narrowly topped 130mph as it had done two years earlier.

If all of this wasn't enough, its late arrival ensured that the team really shot itself in the foot. Time was running short for the team to sort out the car. Most of the top drivers who knew their way around the Speedway were still available. Freddie Agabashian was one driver who gave the car a try but the car was said to handle badly, with a top speed that was too low. An undisclosed Italian mechanic who was familiar with the 375 was flown over to Indianapolis to assist in dialing the car in. His lack of local experience with the Speedway was another reason why Ferrari #47 stood little chance of making a decent impression at the Speedway. Another driver listed to have driven the car was Danny Oakes. But the “500” started with 33 cars as usual, and each and every one of them would be powered by a 270 CI (4.5-litre) Offy.