Ferrari at Indianapolis: mutual love unanswered

1956: A 'hybrid' against one of Indy's most persistent jinxes

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- December 5, 2012; updated: March 26, 2020

Related articles

- March-Porsche 90P - The last oddball at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, by Henri Greuter

- March-Alfa Romeo 90CA - Fiasco Italo-Brittanico, by Henri Greuter

- The Race of Two Worlds - The 1958 "Monzanapolis" bash, by Darren Galpin

- Ferrari at Indianapolis, by Henri Greuter

- 1951: Ferrari and Indianapolis

- 1952: Ferrari at Indianapolis

- 1958: At home against Indycars

- 1961-1968: Of phantoms and enfants terribles

- 1971-1973: 'Meet my uncle Franco'

- 1975: A loud insect never leaving the chrysalis as was intended and hoped for…

- Intermezzo: Ferrari and turbocharging

- 1986: Projects 034 and 637, mere blackmail tools?

- 2000-2007: It's Indy, Gino, but not as we know it

- Appendix: The cars

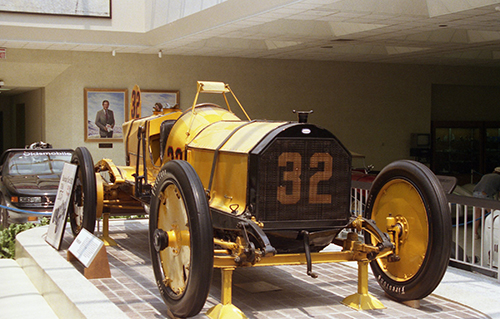

Who?Nino Farina What?Kurtis-Ferrari Bardahl Special Where?Indianapolis When?1956 Indy 500 |

|

Why?

This chapter was updated early 2020. The book The Race To Make The Race, Indianapolis 1954-1963, written by Greg Littleton, contains some additional details about the efforts discussed in this chapter. Permission to quote relevant information from the book was obtained from Greg Littleton and is included in this updated version of the chapter.

Ferrari's next - and third - Indy project, also in the fifties, appears to be the most promising of attempts undertaken in that decade, and perhaps it was the one with the best planning as well, at least if it came to the equipment to be used. In 1955, the Italian office of the Bardahl oil company financed the construction of a genuine Kurtis roadster: a type 500D, with chassis number #387-55. The car was brought over to Italy. At the Ferrari factory, while being looked after by and with support of factory staff and Enzo Ferrari, a six-cylinder engine of the Le Mans-type 121 engine was fitted to the car. This engine, with serial number 0630, had a bore and stroke of 102x90mm, giving a capacity of 4412cc, well within the 4.5-litre limit. The compression ratio was given as 9.0 to 1. This type of engine had become best known as the 121 but was also known as the 446S or 735LM when using Ferrari's traditional manner of using the capacity of a single cylinder. Power outputs of 360hp at 6300rpm to 380hp at 6500rpm have been given for this engine. Carburation was by three Weber carburettors, type 500DCO/A3. Hilborn fuel injection was tried but discarded in favour of the carbs.

Power-wise this engine was in the ballpark as Offies were producing similar power figures. I haven't found torque figures for the Ferrari but since it was an oversquare engine I wonder whether it reached the values of the long-stroke Offy. In that case, as in 1952, acceleration out of the corners was looking suspicious for this engine. Perhaps this may explain why the car wasn't fitted with two-speed gearbox that was standard for Offy roadsters but a three-speed instead.

Sadly, the car wasn't ready in time for what became a dramatic Month of May. One year later, however, carrying Bardahl sponsorship. the car was present, to be driven by the 1950 World Champion Dr. Giuseppe (Nino) Farina. The car arrived somewhat late on May 12, and by then practice had been on the way for quite some time. Farina had already been on the track, having taken his rookie test in a Ferrari 375. The car, the 0338 we already mentioned, was also entered as a Bardahl Ferrari but entered as #91 in the name of Luigi Chinetti's wife, just like in 1954.

The Kurtis-Ferrari hybrid was handed over to and maintained by Americans Paul Meyer and Jess Beene. Even though they knew a thing or two about oval racing, with midgets in particular, this was their first experience at Indy. So they had the disadvantage of having little to no personal experience at the Speedway while neither had their assigned driver.

A Ferrari-powered hybrid remains a rarity.

(photo Bob Mount Pictures, courtesy of First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

If that wasn't enough a of setback, the chemistry between Farina and the pair was missing. It's mentioned in the 1956 Clymer that the crew was a mixture of American and Italian mechanics who failed to understand each other due to language problems. According to Paul Meyer, who has talked about his 1956 Indy experiences, Farina's unfamiliarity with Indy expressed itself by the Italian being unable to find the groove and his inability to discover the way to drive fast at Indy. He used the brakes too much and as a result wore them out way too fast. Now had he been fast enough…

Farina had received help from two American drivers who also sorted out the car. One of them was rookie Johnny Baldwin. On first thought you may wonder what he could have added to helping out Farina, but Baldwin also drove the #91 V12-powered car, so the team obviously had some kind of faith in him.

The ungainly looking 0388 was back for another crack at the Speedway. But how serious could we take this entry? Johnny Baldwin was driving the car. (photo Bob Mount Pictures, courtesy of First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

Another helping hand came from the far more experienced Freddie Agabashian. He had been one of the most surprising pole winners ever when he put the unusual turbocharged Cummins Diesel on the pole in 1952. But still all that assistance wasn't enough for Farina to find the necessary speed.

Agabashian went out in the car on Monday, May 21, and was has been quoted as telling that the engine needed some work but the car handled beautifully. Other assistance to the US-bound team was provided by Ferrari itself: they had sent chief mechanic Luigi Parenti to Indianapolis.

Farina blamed the Americans for doing a poor job on the car. This was too much to accept for them and they replaced Farina with rookie driver Earl Mutter who, with speeds of over 136mph, was instantly faster than Farina! The temperamental Italian then insisted on getting his car back. Meanwhile, changes to the car and engine caused all kind of arguments. The original carbs on the engine were replaced by a Hilborn fuel injection system but Meyer wanted to change over to the use of methanol.

In his book The Race To Make The Race, author Greg Littleton included the following about this situation that took pace on Friday, May 25.

Nino Farina has been struggling in the Ferrari, which had recently been using gasoline instead of methanol. It seems this was Farina's choice. Ollie Bardahl ordered Chief Mechanic Jess Beene to switch the Ferrari back to alcohol. Apparently Mr. Bardahl and Farina are not seeing eye-to-eye on this matter and Bardahl stated: "If Nino will not drive it with alcohol, we'll get another driver." Farina has been running laps, with effort, around 131. Earl Motter was asked to take the car out and immediately turned in a lap of 136 using alcohol. Beene said that when Farina would come in from a run the brakes would be smoking hot but they were not hot at all whet Motter pulled in. Another crewman said, "I don't think Nino wanted to go fast."

The interesting question for which no answer has been found yet is of course why Farina was refusing to run on alcohol fuel and insisted on using gasoline. It was the preferred fuel of choice at Indy at that time. I have not found specific details about how much the actual Ferrari engine block had been modified in order to run on methanol.

On one occasion the Americans seriously suggested taking out the Ferrari engine to install an Offy instead! This was logical thinking: there were more Kurtis 500D chassis around and with Offy power most of these were faster. So the one thing different on the Bardahl car was most likely the culprit, that is, if a driver that wasn't decent enough was omitted as a variable.

The situation became confusing when Farina dragged representatives of the sponsor (Bardahl) into the matter. These made it clear that the Ferrari engine remain in the car and that Farina was its driver. Practice time was nearly over by that time, the last weekend of qualifying was coming up.

Putting a new driver in the car with the aim to qualify the car within two days of time, the chance of such a plan to succeed looked small. Even for a well-experienced driver it would have been a challenge to sort out the car, 'blend' within the team, and make it into the field. There were still four spots open in the field, to be filled that last weekend. But the Saturday (May 26) rained out entirely, but yet there was still one day to go.

However, the last day proved to be a near wash-out. Speedway management had promised a guaranteed qualifying time of two hours once track conditions permitted such. Eventually qualifying resumed, and the field got filled too. 63 minutes of the promised time were still left when again rain started to fall, so Speedway management announced that these 63 minutes would be honoured the next (Mon)day. But according to the 1956 Clymer you must have been at the track that day to believe the flooding because of the torrential rain. With the race scheduled for upcoming Wednesday and the Speedway staff faced with the monumental job of preparing the facilities to make the race possible, the management had no other option than to declare the field as filled and final. This didn't sit well with the entrants denied an attempt to qualify. But eventually common sense prevailed and the unlucky drivers and owners accepted the situation.

For the record: Duke Dinsmore was one of the four drivers who did manage to put his car in the race and his speed of 138.43mph was the slowest of all drivers in the race. So what chance Farina or any other driver in the car would have had to qualify?

And indeed, it took a mammoth effort of the track management to prepare the facilities so that the race could actually be held and to accommodate the massive crowd in the infield as usual.

The 1956 winning car was A.J. Watson's first car he built all by himself, driven by Pat Flaherty. Here it is seen in 2006 in the IMS Museum as the centrepiece in a recreation of a garage as they looked in the old Gasoline Alley that was torn down in the mid-eighties. You can see how Watson-built roadsters had their engine installed: upright and as far to the left as possible. (photo HG)

So the Kurtis-Ferrari hybrid had failed because of all kinds of reasons. This wasn't strange at all since history, or rather Indy tradition, was against the car. Back in 1956 people may have been forgiven for failing to notice why even beforehand the Bardahl car didn't stand a chance. With another fifty years of history to look back upon, however, it's much more obvious to understand why the Bardahl Ferrari was doomed to fail, if only because of sheer tradition alone.

Indy has at least two well-known curses or jinxes. The oldest of those is the Novi jinx. The 1952 part mentioned the Novis already. Part of their legendary status at the Speedway, apart from their speed, was the incredible amount of misfortune that befell these cars. The Novis didn't win a single race but some of their bad luck can be traced back to wrong planning, engineering and unsuitable components.

The second one is more recent: the Andretti curse. Mario Andretti won the fifth “500” he participated in and appeared destined for more Indy glory, but in the 24 starts that followed he rarely made it to the finish, let alone came close to winning the race. At least Mario won a race. His son Michael was denied that pleasure, as was Mario's second son Jeff. Their nephew John was also denied the satisfaction while Mario's grandson Marco is still looking for his first ever “500” victory. Marco was so unlucky to be the first driver to get out of Turn 4 in the lead and head for the chequered flag before being beaten on the final straight. Recently, JR Hildebrand equalled the performance so Marco can console himself by knowing he isn't the only one who suffered that particular fate.

Another persistent curse that was very stubborn yet knew a couple of exceptions is the 'once-a-dozen' jinx that befell Lola. From the mid-sixties until 1996 Lola entered cars in most of the years during this period. In the years between 1989 and 1996 the amount of Lola cars in the field handsomely surpassed 50%. Nevertheless, despite such huge opportunities of victory Lola can only boast three victories: 1966 by Graham Hill, 1978 by Al Unser Sr and 1990 by Arie Luyendijk, all three exactly 12 years apart. In all other years, even with the field on occasion containing up to 25 Lolas, they were beaten by a non-Lola minority, most often a Penske. Now compare this to only three Galmer cars ever having raced at the Speedway, in just two editions of the race. Yet one of those three won an Indy 500 (1992).

In other words: for whatever reason, Indy seems to have its own rules and traditions that can't be properly explained. In 1956, Ferrari added to what with hindsight appears to be another jinx keeping the Speedway in a firm grip, even though few realized its presence. Like the 'Once a dozen' jinx that struck Lola this jinx wasn't entirely consistent but allowed for a few exceptions: up until 1956 only the first ever “500” (1911) and the first post-war race (1946) were won by cars with six-cylinder engines. In the years that followed 1956 six-cylinder success remained very limited. Up until 2012 pure-bred racing six-cylinder engines intended for Indy were hardly even built. In the post-war era only a few have been used. Millionaire Joel Thorne used the Art Sparks-designed Sparks straight-six engines in both blown and unblown shape but apart from victory in 1946 these engines didn't set Indy on fire and disappeared after 1949.

The first-ever 500 winner was the Marmon Wasp driven by Ray Harroun. It was one of only a few six-cylinder-engined cars in the field and incredibly enough the only pre-war race winner using a six-cylinder engine. (photo HG)

George Robson won the 1946 Indy 500, beating the 'six jinx' with only the second car ever that won the race with a six-cylinder engine. If that wasn't unusual enough, the car was also to be the last ever to win at Indy using a mechanically driven (centrifugal) supercharger. But was the 'six jinx' perhaps involved with the fact that a few months later George Robson lost his life in a crash? (photo HG)

It appears as if after 1946 Indy was struck by a curse for six-cylinder engines, can we call it the 'six jinx'? So do you need more support for the existence of such a 'six-jinx'?

Before the war Harry Miller designed a straight-six for his fabled 4WD, rear-engine Miller Gulf cars. It's a story in itself to explain why these cars failed and why after the war we only saw a very few appearances. Then there was Joe Lencki, a most remarkable character who had ordered a straight-six with the Offenhauser Engineering Co. This was an engine described as effectively a six-cylinder Offy. Lencki entered the engine in the last few years before the war and on an irregular basis in the post-war era as well, but after 1949 it never qualified for all kinds of reasons. So it is fair to conclude that the lack of success for 'sixes' was related to the small number of such engines appearing at the track, and that those that did appear didn't make enough of an impression to encourage further use of the concept.

The 'six jinx' remained in force well after the failure of the Kurtis-Ferrari. Few sixes were tried in the years that followed. The most prominent one was Porsche's flat-6, a car with two (!) Porsche flat-sixes (each driving one axle) practiced in 1966 but failed to qualify, but that car at least appeared at the track.

It didn't happen on track but another story illustrative of the six jinx's effectiveness was about the 1980 Porsche engine. This engine was derived from a production unit, the ever faithful 911 engine. It never even appeared at Indy when rule makers 'abused' the fact that it was a six-cylinder to keep Porsche out of Indy. Involved in a controversy regarding boost levels permitted for engines with a given number of cylinders, the rule makers declared that only four-cylinder engines were permitted a boost advantage over other engine configurations. In other words: sixes were seen as equal to an 'eight' but the only victim of the rule was the one engine USAC wanted to keep away from the Speedway. 1980 was the second year of the controversy between USAC and the newly formed CART organisation but it has been said that the only thing USAC and CART wholeheartedly agreed on was that both didn't want Porsche factory participation.

Attempts with V6s of stock-block heritage, however, were welcomed in the mid-eighties but yielded only a single third place as best ever result. There were certainly some serious attempts with such engines but with hindsight we must conclude that the results seem to tell that an engine with a production background simply wasn't the right starting point. Some of the efforts and results obtained with these engines read like a big joke.

It required a 2012 rule change making V6 engines the only allowed engine option to get a winning car powered by a six-cylinder engine. With all 33 starters running a six-cylinder, the 'six' couldn't lose anymore, so the 'six jinx' was finally over and done with. But the mishaps that befell the 1956 Kurtis-Ferrari fit perfectly in the sorry history of 'sixes' at Indianapolis, and surely contributed to the 'six jinx'.

This entire 1956 Kurtis-Ferrari enterprise got an strange footnote after all. Based on what we saw of Farina's success, one would imagine him not to return to Indy anymore. Yet that is exactly what he did in 1957. This time, however, he drove a regular Kurtis-Offy roadster. But things did not go well again for Farina and on May 15, he had the car being testhopped by Keith Andrews. Regrettably, Andrews crashed the car and was killed at the spot. The car was not repaired and Farina called it a day for that year and all his Indy attempts.

Special thanks to Greg Littleton for the permission to quote from his book The Race To Make The Race.