Tin-top kings

Author

- Mattijs Diepraam

Date

- July 30, 2010

Related articles

- Carel Godin de Beaufort - The last knight of Grand Prix racing, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Hans Herrmann, Jo Siffert & Jochen Mass - Three generations of sportscar superiority, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Hans Heyer - One for the record?, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Tom Kristensen, Gil de Ferran, Dario Franchitti & many others - Missing out on F1, by Mattijs Diepraam

- JJ Lehto - A bad crash at a bad time, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Gijs van Lennep - As smooth as aristocrats can be, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Bernd Schneider - AMG's Bernd rubber, by Mattijs Diepraam/Andrew Winter

- Nino Vaccarella & Bob Bondurant - Sportscar greats of the sixties, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Manfred Winkelhock - German's single top F1 drive, by Rainer Nyberg/Mattijs Diepraam/William Dale Jr

Who?Steve Soper/JJ Lehto What?BMW Motorsport McLaren F1-GTR Where?Donington Park When?1997 FIA GT Donington 4 Hours (September 14, 1997) |

|

Why?

Most motor racing history’s sportscar and touring car greats once actively pursued a single-seater career before settling down in the tin-topped world of prototypes, GTs and saloon cars. Toine Hezemans, Steve Soper and, to a lesser degree, Klaus Ludwig are the exceptional exceptions to this rule of thumb.

Instead of failing to make it to Formula 1 Hezemans and Soper never showed any real interest in open-wheeled machinery, preferring to grow their rich and satisfying careers by exclusively racing cars with fenders and room for at least one passenger, while young Ludwig's career in touring cars was already fully blossoming during the years he double-timed in single-seaters. As they did so this trio of tin-top kings became the yardstick for legions of single-seater refugees attempting to become the new Hezemans, Ludwig or Soper.

Heat heze

Motorsport is filled with famous families, but the Hezemans family from Holland is among the few that can boast a motor racing heritage going back for three generations. Like the Pilettes and the Andrettis, granddad was the first Hezemans to drive racing cars, with grandson still very much active in GT racing today. Toine Hezemans – son of Thieu, father of Mike – is the middle man in the Hezemans generation game and arguably the most successful of the three. He has one thing in common with father Thieu and son Mike, though – all three never so much put a thought into starting a single-seater career.

Born into motor cars, Toine profited from traveling to the circuits at a very young age. While dad remained a gifted amateur earning his money through his Porsche dealership, at one time giving the career of Dutch sixties hero Carel Godin de Beaufort a decisive boost, Toine quickly grew into the consummate tin-top professional, becoming a major factor of the works efforts by Abarth, Alfa and BMW. Gifted with engineering nous and a keen sense of vehicle dynamics, which started developing when as a teenager he built his own Porsche-based special, Toine was the mechanic’s dream when it came to technical feedback.

What is today considered the usual route for aspiring youngsters – stepping up from karts – came natural to Hezemans, even though he was among the first to successfully make the switch. Again, father Thieu was instrumental, owning one of the first karting tracks of the Netherlands, in Vaals, also the site of the country’s one and only hillclimb event. Toine never cut his ties with the karting world, as he would later take over the role as Holland’s official Rotax importer. The Hezemans family still runs an indoor karting centre in their native Eindhoven, one of the first to open in the country.

Toine in front of the Gelo truck at Zandvoort during his time with the Weinberg-sponsored Porsche team.

(photo Cor van Veen, used with permission)

Toine shifted his attention to cars in the mid-sixties and competed on a national level, racing Alfa Romeos and Porsches at Zandvoort, Vaals and Welschap, the local Eindhoven airfield track, against rivals such as Gerard van Lennep, Hans Koster and team mate and team boss Ed Swart. His first national title came in 1966 when he won the 850-1000cc class of the Group 2 Dutch touring car championship racing an Scuderia Auto-Swart (SAS) Racing Abarth 1000TC. In the four-race championship, he often outgunned the 1300cc Minis of Dudok van Heel and Oskamp and also won Vaals overall by entering in all three classes and taking BTD in the Stichts Racing Team (SRT) Alfa 1600 GTA, beating mercurial talent Wim Loos.

His talent was soon noticed across the small country’s borders, and at the next event – the traditional late-summer Trophy of the Dunes at Zandvoort – Toine brought an official Autodelta GTA, and to make people sit up some more he took a fine second place in Division 1 of the Limbourg GP round of the ETCC at Zolder, racing the Swart Abarth, and added a third place in the late-season Zandvoort round. Abarth soon supplied Swart and SRT with works-prepped vehicles, Hezemans following Swart into Europe. A first Division 1 class win came at no less a place than the Nürburgring in 1968, Toine sharing an SRT Abarth 1000TC with Ab Goedemans after their works car failed in practice.

With Swart staying in Division 1, it was time for young Toine to move up to the big boys, as SRT entered a Division 3 Group 5 Porsche 911 for Toine and Bob van der Sluis. Toine immediately made his mark in the opening race at Monza, dominating until the engine gave up. In Budapest, Toine finished third in class, the overall win going to Gijs van Lennep’s DNRT 911. After another third at Brands Hatch, Toine teamed up with Gijs to win the Nürburgring 6 Hrs in the SRT Porsche, beating Autodelta’s De Adamich/’Paco’. At Zandvoort, Hezemans followed up with another unbeatable performance, gaining him third in the championship.

The Hezemans/Van Lennep Porsche chasing the Dieter Basche/Dieter Glemser BMW 2002 Ti turbo and the Rolf Stommelen/Georg Loos Porsche 911, the early leaders in the 1969 Nürburgring 6 Hrs. (photo Jim Culp)

It was all change in 1970, when Group 2 and 5 were mixed into a new set of regulations. In the interim state of manufacturers playing themselves in with the new rules, Alfa got it dead right by homologating a mean-looking lightweight 1750 GTV named 2000 GTAm, and signing the Porsche driver that defeated them at the ‘Ring in the previous year. As it was, Hezemans ran away with the title by winning at Monza, Budapest, Brno and Jarama. He added some fine sportscar success by finishing third at Sebring, sharing an Autodelta T33/3 with Masten Gregory.

Ford getting a hand of the rulebook meant a Capri RS2600 whitewash in 1971 but Toine still won the opener at Monza while a string of class wins kept him in the hunt for the overall title until the final round. At Jarama, he finally had to succumb to Dieter Glemser. Helping out Autodelta in their sportscar effort brought more success in 1971, as Hezemans joined local hero Nino Vaccarella to claim a popular Targa Florio win in front of the jubilant Sicilian crowd. Again with Vaccarella, he took fifth in the Nürburgring 1000kms.

The Hezemans/Vaccarella pairing finished third in the 1972 Sebring 12 Hrs, and joining Facetti Toine took fifth at the traditional ETCC opener at Monza, but that was the end of Toine’s involvement with Alfa Romeo, as Autodelta gave up its challenge to Ford. In sportscar racing, he returned to Abarth to team up with Arturo Merzario in the Abarth-engined Osella SE-201, while in touring cars he switched to BMW, which had now become Ford’s main rival. Driving for Alpina, he took third at Zandvoort, with Gerold Pankl and a young Niki Lauda as his team mates. A one-off in the Frami Capri at Silverstone and a Div 1 GTA at Jarama saw Hezemans end a relatively dismal season.

He was back with a vengeance in 1973, though. In a tough battle with Ford, Toine’s Alpina slowly gained the upper hand, and he followed up three second places with three consecutive wins at Spa (the blue-riband 24 Hrs), Zandvoort and Paul Ricard, helped by rapid Austrian Dieter Quester being switched to Toine’s car, replacing Australian Brian Muir. Hezemans finished the season as the clear champion, ahead of Muir, Quester and Ford’s Jochen Mass.

A switch to Ford in both national touring cars and the ETCC, joining former rival Glemser in the European Ford Köln effort, failed to act as a lucky charm to the Cologne team, Hezemans’ first 1974 victory only coming in the final ETCC at Jarama. Toine was now thirsty for even more powerful cars and so he joined the Gelo (Georg Loos) team, initially to be part of their WSC effort, but also taking in the European GT championship from 1975 on.

Unique footage of the 1971 Nürburgring ETCC meeting, with all the big guns present.

European GT initially ran as a trophy but was later given championship status by the FIA. Conceived as a battling ground for Porsches, Ferraris and De Tomasos, Porsche proved to be the dominant force, and it still was when Hezemans joined the championship in 1975. Essentially a battle between the Gelo and Tebernum teams, the 1975 title race became an affair to be sorted between championship regulars John Fitzpatrick, Clemens Schickentanz and Hartwig Bertrams, the latter taking the honours in the all-conquering Carrera RSR. Hezemans finished third in the championship.

With Kremer back for 1976, Gelo and Tebernum joined forces in the final year of Euro GT. The new Porsche 934 Turbo proved to be a bull ride but when the driver remained in the saddle would be unbeatable against the ever shrinking competition. Tim Schenken joined Hezemans at Gelo-Tebernum, while Wollek and Heyer were signed by Kremer. Max Moritz also entered a pair of Jägermeister-liveried 934s for Kelleners and Stenzel but the depth of the field was shallow to say the least. Hezemans won the championship by winning five of seven rounds, after which Euro GT was dead and buried.

All of Germany’s Euro GT stars, however, had their main podium elsewhere: the Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft, with its own peculiar mixture of touring car and GT rules, allowing the crop of the ETCC and Euro GT to compete on level terms. This meant that Ford, BMW and Porsche were battling it out annually on their home ground, as the DRM circus travelled from the hallowed grounds of the Nürburgring and Hockenheim to airfield circuits such as Mainz-Finthen, Diepholz and Kassel-Calden, and the place that would DRM’s (and later DTM’s) spiritual home, the Norisring.

Hezemans’s first acquaintance with the DRM came at the 1973 Eifelrennen: he took pole and won but was ineligible for points. He repeated his pole in the 1974 edition but finished second to Stommelen’s similar Capri RS3100. Another guest appearance followed in the 1975 Geldrennen (‘Money Race’), an additional all-star race at the Norisring. In Gelo’s Carrera RSR Toine beat team mate John Fitzpatrick to the big prize. In fact, it was a gift in return to the Dutchman moving over for ‘Fitz’ in the Euro GT support race.

1976 was Toine’s first full season of DRM, combining it with his European GT programme. Division 1 driver Hans Heyer easily won the championship but Toine did win three Division 2 races, including the German GP support race in the aftermath of Niki Lauda’s fiery accident.

In 1977, the DRM decided to follow Group 5 rules, which was a big success initially, as it allowed in the mighty Porsche 935s. In the early Group 5 seasons, DRM was effectively the place to be, as the World Sportscar Championship barely survived its barren years. Hezemans joined the Division 2 Ford Grab Weisberg Werkzeuge team but rarely managed to score in his Escort II RS. Still part of the Gelo WSC team, Toine together with Stommelen and Schenken won the Nürburgring 1000kms and came third in the Silverstone 6 Hrs. A third Le Mans appearance for Gelo, however, came to nought when the team’s two cars were retired after having qualified 8th and 9th. A guest appearance in the Zandvoort ETCC race, joining runaway champion Dieter Quester in the Alpina-BMW 3.0 CSL, led to inevitable victory.

Hezemans heading local hero Toine Suykerbuyk through the Hugenholtzbocht at Zandvoort.

(photo Cor van Veen, used with permission)

Hezemans’s final year of glory came in 1978 when he won four major sportscar races in the Porsche 935, including the Daytona 24 Hrs, in which he joined Rolf Stommelen and Peter Gregg in the Brumos team. Driving for Weisberg Gelo, he also won at Mugello (with Fitzpatrick and Heyer), the Nürburgring (with Heyer and Klaus Ludwig) and Watkins Glen (with Fitzpatrick and Gregg). The win at the Glen was made famous when the trio finished the 6-hour race with a 935 that was missing the driver-side door. A broken piston, however, continued Toine’s luckless run at the Sarthe, that had started so well with fifth overall and a Group 4 class win in Gelo’s Carrera RSR in 1975. The WSC wins were by an equally impressive run in the DRM, where Weisberg’s money had now been transferred to the Gelo Porsche team in Division 1. It turned Hezemans into a fiersome title challenger, and he only just lost out to Division 2’s Harald Ertl, although the Dutchman was the best of the Div 1 runners, ahead of Kremer rival Bob Wollek and Gelo team mates Fitzpatrick and Ludwig. His title chances ran aground by retiring at the Norisring but also by falling out with team boss Georg Loos and a ill-concealed attempt to strike a deal with the Martini Porsche works team.

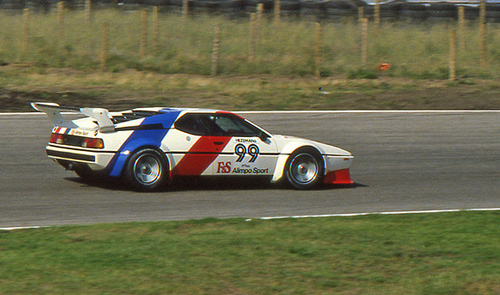

His fruitful liaison with Loos having ended in acrimony, a final challenge awaited Toine in 1979 when, with the support of F&S Properties (the controversial real estate company run by Ton Fagel and Bob van der Sluis), he joined the BMW M1 Procar trail. Hezemans and Van der Sluis had remained friends since their joint days in Dutch touring cars – even though Bob had won his 1971 up-to-1300cc title by turfing Hezemans off the road, which eventually led to a suspension of his racing license and subsequently cost him a lucrative BMW works deal. Their respective children Mike and Chantal would later earn their first marks in karting with the Hezemans Rotax team. In the No.99 Team Alimpo M1 supported by BMW Holland, Hezemans took on celebrity rivals such as Lauda, Jones, Piquet, Fittipaldi, Regazzoni and Andretti.

Procar originated from a FIA decision that would have rendered the M1s obsolete for Group 5 racing. Instead, BMW competition boss Jochen Neerpasch came up with the idea of a one-make series to still make use of their expensive machinery, and to attract name drivers the series would join Grand Prix weekends on the European continent, setting the scene for what is now common with the Porsche Supercup and the GP2 Series. BMW Motorsport would hand out five of its M1s to the five best drivers from Formula 1 practice, with respected touring car teams such as Schnitzer, Eggenberger, TWR, Konrad and GS Tuning filling up the field. Project Four would enter a car for Niki Lauda, and Osella entered BMW Italia-supported cars for a rotating line-up including Bruno Giacomelli and Elio De Angelis.

Toine in the Alimpo Sport-run M1 at Zandvoort in 1979. (photo Cor van Veen, used with permission)

The touring car specialists signed up the big names of their trade as well: Quester, Kelleners, Höttinger, Stuck and Brun were among the tin-top stars challenging the F1 guns. Hezemans ho proved to be suitably adapted to the challenge as well. While failing to win a race he picked up enough points positions, including second in the season opener at Zolder to finish fifth in the 1979 standings. In the DRM, meanwhile, Toine showed up in the Eifelrennen with an experimental overbored Division 1 Capri III Turbo. Even though it failed to stand up against the phalanx of 935s it managed to beat Marc Surer’s works BMW M1.

When Toine quit racing he quickly transformed into a constructor and a team boss, today still running the Carsport Holland team in FIA GT. His entry into GT Racing, along with son Mike, came in 1996, when he took over the Lotus effort in the BPR GT championship lock, stock and barrel. Proving his versatile business exploits, Hezemans also developed real estate in the US and the Dutch Antilles and at one time even owned his own airline.

King Ludwig

The careers of Toine Hezemans and Klaus Ludwig overlapped during their DRM days, culminating in 1978 when they became team mates at Gelo. At that time Ludwig’s biggest triumphs would still lie ahead of him, though, starting the very next year when he took his first title of international acclaim by becoming the 1979 DRM champion. He would repeat the trick in 1981.

Klaus Ludwig is Germany’s most successful tin-top driver by far and hence fully deserving of his nickname König Ludwig (‘King Ludwig’). As opposed to his touring car contemporaries Stuck, Stommelen, Mass and Ertl he never competed in a Formula 1 race, although he did race at F2 level when in 1976 he raced Willi Kauhsen's uncompetitive March-Hart 762 to three points-scoring finishes at the Salzburgring, Nogaro and Hockenheim, while taking third in the non-championship Eifelrennen. But did he have any need to be successful in single-seaters? By then, Klaus was already the man everyone wanted to have under their roof.

Ludwig made his DRM and ETCC debut in 1973 when Hezemans was at the height of his ETCC power. As a youngster teaming up with Karl Ludwig Weiss in the Grab Ford Siegen Capri RS2600, Klaus finished fifth (and best-placed Ford) in the Nürburgring round of the ETCC. One month later, at the very same ‘Ring, he finished ninth, right head of Weiss, in the August DRM race. From that moment on, Ludwig would be a regular in both championships.

Still with the semi-works Grab Ford Siegen team, his first DRM win came the following season, when he took victory in the Hockenheim Preis der Nationen (‘Nations Prize’). With Heyer, Ludwig crowned the year with a remarkable victory in the 6-hour ETCC Nürburgring enduro also counting towards the DRM when the pair beat the big Division 1 cars in their Escort RS1600. Klaus finished his first full DRM third in the final standings, also adding three second places and two thirds to his tally. Ludwig gained third place in the 1974 ETCC rankings as well, helped by his 6-hour win, a fourth at Vallelunga, a sixth at Zandvoort, and another win at Jarama, sharing with both Heyer and Hezemans in the works Capri.

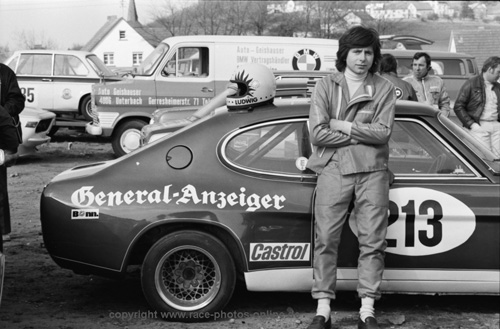

Two wonderful pictures of a very young Klaus during the Nürburgring 300km event in 1973.

(photos Rudolf Schoettel, used with permission)

Ludwig failed to appear in the ailing ETCC in 1975 but made sure he was right here at the top in the DRM, where Zakspeed Ford team mate Hans Heyer became his closest championship rival, along with Albrecht Krebs in the Division 1 Schnitzer CSL. With the aim of monopolizing all the Division 2 points, the powerful Escort RS helped Heyer and Ludwig slug it out for overall titles honours. Heyer had been the natural successor to Dieter Glemser, while young Ludwig was placed at Zakspeed at the behest of Ford Cologne.

Erich Zakowski, however, feared that the two would be taking too much points from each other in their battle against Jürgen Obermoser’s BMW, and there was more unease when Zakspeed wasn’t just entrusted with Ludwig but with the works second-generation Escort as well, while Zakowski thought he could do a better job. He probably did when he completed his own second-generation Escort RS but the car was fast as well as unreliable. In the middle of the season, Ludwig was switched to the ex-Mass Division 1 Capri in order to take on Krebs and the Porsches while Heyer was left to fight Obermoser in Division 2 in the ex-Ludwig Escort II RS. Krebs’s retirement in the final race at Hockenheim meant Heyer took the title ahead of Ludwig.

In 1976, it was Heyer first and Ludwig second again for Zakspeed, in the final year of DRM’s splendid isolation by still allowing old-school Group 2 and Group 4 cars. Faced with the new challenge of Porsche’s fast but frugal 934 turbo, the Zakspeed pair used their Division 2 dominance to good effect when Gelo’s Hezemans and Kremer’s Bob Wollek failed to capitalize on their Porsches’ speed advantage. Ludwig won his division at the Norisring and twice at the Nürburgring but Heyer won four times to easily edge out his team mate.

Two somewhat lacklustre years followed in 1977 and 1978. Because of his F2 commitments - which became a total disaster in Kauhsen's rechristened Renault-powered Jabouille J2 - Klaus failed to appear as a regular in the first season of Group 5 but gave a quite a demonstration of his abilities when he was drafted in to race the difficult BMW 2002 turbo in the Nürburgring Super Sprint season-closer and won. At Gelo in 1978, Ludwig teamed up with Hezemans and Heyer again, to combine the DRM and the World Sportscar Championship in its underwhelming Group 5 years, and their star performance came at the Nürburgring 1000kms event, when they won on aggregate after a victorious first heat and second place in the second heat. In the DRM itself, Ludwig won one race, the GP support event at Hockenheim, and finished sixth in the final standings.

An inspired switch to the rivals at Kremer set Klaus up for major stardom, as he took the 1979 DRM title by storm in Kremer’s all-conquering new K3 version of the 935. Up against Gelo’s superteam of Wollek, Fitzpatrick and Schurti and the Liqui Moly Joest duo of Stommelen and Volkert Merl, he won all eleven DRM rounds bar one (and finished second in that one). This meant he was a shoo-in for the overall title, as Division 2 rivals Heyer (Zakspeed Capri III Turbo) and Manfred Winkelhock (Schnitzer 320i Turbo). With team mate Axel Plankenhorn, Ludwig was also successful in the World Sportscar Championship, finishing second at the Nürburgring (albeit beaten by Gelo’s supertrio) and at Brands Hatch (trailing Joest’s remarkable rejuvenated 908/3). Moreover, teaming up with the Whittingdon Brothers, Kremer and Ludwig won ahead of two Dick Barbour 935s at Watkins Glen.

The Ludwig/Niedzwiedz Sierra Cosworth on display at AMI Leipzig. (photo eplusm)

Group 5, however, was now at the point of falling over its own cost spiral, and the Group 5 depth kept on dwindling in 1980. Ludwig and Kremer fell out ahead of the DRM season, and even took their conflict to court. The reason was an offer one can’t refuse by old love Ford to the new DRM champ: a new Division 1 Capri III Turbo. Ludwig signed on despite his Kremer contract still running for another year. He eventually won, leaving Kremer to promote Plankenhorn to its position as lead driver. There was sweet revenge at the traditional opener at Zolder where Ludwig’s Capri failed scrutineering, while anger raged in the final corner of the Jim Clark Memorial at Hockenheim where leaders Ludwig and Plankenhorn tried to claim the same piece of asphalt. Ludwig was first to recover and thus won ahead of the hapless Kremer team. It was the first of five wins but it wasn’t enough beat Heyer for another DRM crown. BMW’s Stuck also finished ahead of Ludwig in the final standings. Klaus made amends in 1981 by driving the Division 2 Zakspeed Capri Turbo to his second DRM title, again being nigh unbeatable, before entering into the Group C era.

Initially staying with Zakspeed and Ford to join Winkelhock, Surer and Klaus Niedzwiedz for a flawed WSC campaign with the dismal C100, but soon switching to Joest, a new chapter in Ludwig’s tin-top career started. Klaus formed formidable pairings with Bob Wollek and Henri Pescarolo, and a sixth place at Le Mans in 1983 (with Wollek and Stefan Johansson) was followed up by triumphs in the 1984 (with Pesca) and 1985 editions (with Paolo Barilla and ‘John Winter’). The same winning trio failed to finish in 1986, although Ludwig did set fastest lap. Klaus’s WSC outings with the Zakspeed Ford C1 remained disastrous, however, while he also made occasional appearances for Kremer, their early-eighties row now long forgotten.

Meanwhile in DRM, the C100 proved as difficult a beast as in the WSC, Ludwig and team mate Niedzwiedz reverting to the Capri Turbo at times to haul in the points. Klaus did manage to win twice in 1982, however, at Hockenheim and the Nürburgring, while Joest still had to make do with Porsche’s 936. Nonetheless, Wollek was champion for Joest. With the 956s on steam there was no stopping Bob Wollek in 1983, and Stefan Bellof (Brun) and Jochen Mass (Joest again) after him. Zakspeed’s own C100’s conversion, the C1, proved to be equally fast but flawed, Ludwig invariably setting fastest laps of the race before heading towards another retirement, although the C1 eventually became a contender in DRM’s swansong season in1985, and won against lesser opposition in the Interserie championship, allowing Niedzwiedz to take the 1984 title.

The James Hardie Bathurst 1000 was included in the 1987 WTCC, and Ludwig and Eggenberger stunned the locals by putting the Sierra on pole at the Mountain. The Soper/Dieudonné sister car went on to win, ahead of Ludwig/Niedzwiedz, but it all came to nought when months later the Sierras were eventually disqualified.

In 1987 Ludwig decided to leave the fast and dangerous world of Group C racing, moving to the WTCC and embarking on the new DTM trail, born from the decision to open up the DRM to Group C sportscars. Slowly taking over the traditional DRM calendar, the DTM burst into prominence when the DRM finally collapsed in 1985. Klaus had already become an instant winner with the Sierra XR4 Ti, cleaning up the final four 1985 rounds and also guested in 1986 and ’87, winning the Nürburgring round in the latter season. Meanwhile in the 1987-only WTCC, armed with the follow-up Sierra RS Cosworth, he won the Nürburgring, Brno, Wellington and Fuji rounds with Klaus Niedzwiedz, to miss out to BMW’s Roberto Ravaglia on the title by a single point in a championship that was as competitive as it was political.

In 1988, with Mercedes tempted to join BMW and Ford for the first of a run of classic DTM seasons, Ludwig decided to spearhead Ford’s attack full-time. Armed with the new Sierra Cosworth to take on BMW’s E30 M3 and the Mercedes 190E 2.3-16, won the title after a close-fought season, taking double wins at Zolder and Wunstorf and one of the Norisring heats. The WTCC now having reverted to the ETCC, Klaus remained with Eggenberger but his 1988 attempt at international touring car glory ended in fourth place in the championship. Initially having started with 1987 team mate and namesake Niedzwiedz, Ludwig was switched to the Steve Soper car from Jarama on, and it led to three wins, immediately winning at Jarama, then at the Nürburgring (obviously) and in the final ETCC race at Nogaro, after which the rumourous ETCC/WTCC was laid to rest.

The ETCC now over, the reigning DTM champion made a surprise switch to Mercedes in 1989, the marque he would become synonymous with until the twilight of his career. He had a hard time defending his title, eventually lost to BMW’s Roberto Ravaglia, and was involved in a serious accident at the Nürburgring when luckless Armin Hahne collected Ludwig’s spinning 190E head-on at 170kph. Hahne broke his arm on impact. Ludwig himself had to skip the Nürburgring 24 Hrs support event because of an acute kidney problem. Luck deserted him in other early-season races as well, and he could only finish 11th in the final standings by virtue of a late-season spree of double wins at Diepholz and the Nürburgring.

Ford pulled out at the end of 1989 when governing body ONS decided to ban turbo engines in favour of 2.5-litre atmospherics. The gap Ford left behind was quickly filled by Audi. Their four-wheel drive quattro and its powerful V8 engine proved invincible against the best that BMW and Mercedes could muster. BMW’s Johnny Cecotto became Audi’s main rival in 1990 but it was Ludwig who kept his 190E 2.5-16 Evo2 in the hunt for Mercedes until the final 1991 round at Hockenheim. With Audi’s advantage cut back in 1992 – leading to its withdrawal in 1993 – the season was up for grabs for Mercedes. Indeed, Ludwig ran out the convincing champion to become the first to double up DTM titles.

Klaus chasing M3 at Zolder in 1989.

With the new Class 1 regulations for 1993, the newcomer with a bespoke Class 1 design would always conquer. And so it happened, as Alfa Romeo left the opposition for dead with its 155 V6 TI. Ludwig finished fourth in the championship. With the new-for-1994 C-Class, Mercedes went on the counter attack, and Ludwig duly wrapped up his third title. It would take until 2001 before his rightful heir at Mercedes, Bernd Schneider, would equal that statistic and eventually beat it.

Being at the pinnacle of tin-top racing, Ludwig became a first-hand witness of two FIA championships spiralling out of existence by budgets rocketing through the roof. First, the international DTM follow-up called the ITC collapsed, quickly followed by FIA’s first incarnation of its International GT Championship. The German didn’t leave without winning at least one of them, however. He first helped fellow DTM master Schneider to the 1997 title, winning at the Nürburgring, A1-Ring, Sebring and Laguna Seca, before teaming up with single-seater hotshoe Ricardo Zonta in 1998.

By then, the Mercedes CLK-GTR had already trumped the McLaren F1-GTR, the Panoz GTR and Porsche’s 911 GT1. Its follow-up CLK-LM, that appeared at the Hockenheim round in June, was in a class of its own, leaving Mercedes to win all rounds of the 1998 championship. Ludwig and Zonta took the Oschersleben and Dijon rounds, while Schneider and Mark Webber triumphed in five more rounds. The German/Brazilian combination finished runner-up to most of those Schneider/Webber victories, and a late-season push to win three-in-a-row at the A1-Ring, Homestead and Laguna Seca edged Ludwig and Zonta in front of their team mates.

It certainly meant going out on a high for Klaus, as he officially quit his active racing career at the same time Mercedes pulled out of the GT1 championship it had just killed by its dominance. It took a mere half-season before Ludwig made his ‘comeback’, though, and a winning one at that. Driving a Zakspeed Viper, he was part of the crew that won the 1999 Nürburgring 24 hours. His true comeback came in 2000 when the DTM resumed service as the Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters. It would only be for one year but he wouldn’t leave without a win at the Sachsenring. After his second retirement in two years he returned as the official DTM ‘taxi driver’, then as an ‘amateur’ to compete in the Nürburgring 24 hours between 2004 and 2006, joining the Alzen brothers in their Porsche entries. His son Luca is now an upcoming talent in the German ADAC GT championship for GT3 cars, driving for the Abt Audi team.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s Soperman!

Among Ludwig’s chief rivals during their DTM and FIA GT1 days, and a team mate in their time at Eggenberger in the WTCC and ETCC of ’87-‘88, Steve Soper was beginning to make his name as a touring car star chasing glory all over the world. In his late thirties he ended up in what was the pinnacle of touring car racing and eased into GT and even prototype racing when BMW made the plunge, although Steve never made a secret of his hatred of endurance racing.

Soper was a relative late-bloomer, even though he started racing at a very early age. Almost his entire twenties were spent racing Minis, Imps and Fiestas. Debuting at Silverstone club level, Steve switched to Special Saloons Championship and the one-make Mini 1275 GT Championship, which he finally won at his fourth attempt in 1979, already at 27 years of age. He was champion again in 1980, now in the Ford Fiesta Cup, and made his touring car debut in 1981 when approaching his 30th birthday.

Jumping back and forth between the BTCC and the MG Metro Challenge, he became part of Rover’s assault on national touring car glory. Soper won the Challenge, and made his name with several BTCC class wins. He also stretched his legs by racing a Fiat X/19 in the STP Championship. In 1982, the MG Metro class wins continued in the BTCC, leading to ETCC Division 1 appearances. At the time, Division 1 was filled up with local drivers, and so Steve’s ETCC debut came at Donington Park, joining veteran and BTCC team mate Richard Longman in Austin Rover’s Metro. They won their division. Back at Silverstone at the end of the season, they finished an unclassified second in Division 1 but his 1982 form was enough to prove to Rover that Soper was a good bet for the big Rover Vitesse in 1983.

It became a dominant year for Soper, with five wins, amongst which his very first in the Vitesse, to claim the championship – until the moment the hydraulic valve tappets on his Rover V8 engine were deemed to be illegal. Soper and Jeff Allam also did their home rounds of the ETCC, as well as the Nürburgring and Zolder rounds, but to no great success, the Vitesse not quite up to speed with the TWR Jaguars and the Schnitzer and Eggenberger BMWs. Until that day in September, that is, when Soper, now paired with Dakar star René Metge, won the rain-hit RAC TT at Silverstone, beating a phalanx of seven 635i’s. Another two mean feats were his qualifying the Vitesse fifth and fourth at the ‘Ring and Zolder respectively, places he’d never seen before, and ahead of several BMWs raced by drivers with local knowledge. Soper also made his Le Mans debut, as he joined Allam and James Weaver in Mazdaspeed’s Mooncraft-prepared 717, to finish second in the Group C Junior class, only outrun by their team mates Yorino/Terada/Katayama.

The 1984 ETCC season with Rover, Steve first paired to Jeff Allam and then to Armin Hahne and Jean-Louis Schlesser, was a consummate disaster, as the Vitesse recorded an impressive string of non-finishes, all attributed to mechanical failures matching the reliability of Rover’s road cars. It wasn’t until the Salzburgring round in July that Soper finished a race. However, normal service was resumed at the Nürburgring one week later and Austin Rover didn’t even bother to show up at the final two rounds at Zolder and Mugello.

In 1985, TWR picked up what was left of Rover’s works programme when it swapped its championship-winning Jaguar XJ-Ss for a new challenge, developing the Vitesse into a race-winning proposition while it supported Jaguar’s entry into Group C. Soper went along for the ride, as he joined the ETCC team from Donington on, finding himself in the same car with Hahne and Schlesser again, but now in its famous Bastos and Texaco livery, having won the first two ETCC rounds handsomely through the able hands of Win Percy and Tom Walkinshaw himself. These continued merrily on their domination of the early part of the championship, while Steve turned his back-up appearances into success by third at the Salzburgring and second at the Nürburgring, both with Belgian Eddy Joosen, and then second again at Silverstone and Nogaro, with Schlesser.

Meanwhile, however, the Volvo effort by Eggenberger came on strong during the second part of the season, and with one round to spare the Brancatelli/Lindström pairing snatched the title away from Walkinshaw/Percy’s hands. The late-season arrival of Ford’s new Sierra XR4 Ti proved a shape of things to come, and with Eggenberger defecting from Volvo to take up Ford’s challenge in 1986, the Sierra became a car to fear in probably the most hotly contested ETCC season ever – both on and off the track. Soper took the plunge and signed with Ford.

In a topsy-turvy year marred by countless protests, Rover, Volvo, BMW, Ford and occasionally Holden all battled hard for the wins in the top division. Even though the Sierra was quick on occasion – Soper’s pole at Brno and his fastest lap at Silverstone testimony to that – it was unreliable as well, especially in the turbo department. For a long time a third place at Hockenheim and a fourth at Nogaro were the best Steve and team mate Klaus Niedzwiedz could muster. With Sigi Müller, Soper and Niedzwiedz finished sixth in the Spa 24 Hours. It all turned around at the final round at Jarama, however, when the Brit and the German beat the three TWR Vitesses to the win.

It was the prelude to another step up for Soper, as the ETCC morphed into the WTCC in 1987. The world championship became a dismal failure because of a lack of entries and a seemingly endless string of disqualifications, and it was axed after a single year of existence. Only 15 cars were fully paid-up and eligible for points, with Alfa pulling out ahead of the overseas races, and after Ravaglia was handed the 1986 ETCC championship four weeks after the final race had run, the Italian also won the WTCC behind the green table – such was the amount of illegal practice going on. The Monza opener turned into a farce when the Sierras were excluded ahead of the race because of Eggenberger illegally changing its electronic injection while the BMWs were thrown out after the race when it was found that their roof tops were made from fantastically thin sheet metal. Ford was in the docks again at Bathurst when Eggenberger illegally modified the rear-wheel arches. It robbed Soper and team mate Pierre Dieudonné of a famous win, months after they had celebrated it. The pair kept their win at Calder Park one week later but while Klaus Ludwig in the other Sierra RS Cosworth was challenging for the title with a strong late-season run, Soper was left in sixth place in the championship. The best memory of the year came at the Nürburgring where Soper teamed up with Klauses Ludwig and Niedzwiedz to win the 24 Hours.

The 1988 ETCC became another scalp for Ravaglia, extending the Italian’s amazing run of consecutive international touring car titles, but this time Steve came a lot closer, in the end losing out by a mere seven points. In the final Sierra incarnation, the RS 500, Soper won the four of the first five rounds, taking the spoils at Monza, Estoril, Jarama and Dijon and looked on a canter towards the championship but then BMW came on strong, helped by a double points haul at Spa. Ford allowing Andy Rouse private Kaliber-liveried Sierra to beat the Soper/Dieudonné works car at Silverstone didn’t help either. Eggenberger also entered four BTCC rounds. Steve won at Thruxton and came second to Rouse at Brands after an epic tussle.

The thrilling finale to the 1992 Spa 24 Hours, Soper edging out Van de Poele going into the final lap.

The final editions of the ETCC had been thrilling but predictable. The entry numbers kept going down, the protesting had become something of a culture, and the ETCC divisions had turned into Ford, BMW and Toyota monopolies, all leading to the championship’s demise. By default, the DTM would be the leading international touring car championship in 1989. Ford, meanwhile, faced something of an exodus, as Ludwig departed for Mercedes while Soper tied the knot with BMW, the marque he would become synonymous with.

Steve had already guested for Ford in the later parts of the 1987 and 1988 DTM championships, drafted in to help Manuel Reuter and Klaus Ludwig’s title assaults. It gained him a third at the Salzburgring in ’87 and two second places at Wunstorf in ‘88. Now he would be a full-time DTM driver, and a BMW driver at that. Steve’s third DTM, the traditional early-season Eifelrennen, already brought a double whammy with two wins and two fastest laps. Many more fastest laps and numerous top-five placings later, Soper ranked fifth in his first full DTM season.

The Audi years would follow in 1990 and ’91, but still Soper and his M3 Sport Evolution managed to go one better in 1990 to finish fourth in the final standings. Having switched from Zakspeed to Bigazzi, Steve repeated his double win and double fastest in the Eifelrennen and racked up several podiums as well. He was fifth again in ’91, a year of even more Audi dominance. The win-and-fastest-lap double came at Hockenheim this time, releasing him from the Hockenheim jinx that plagued him for so long. More wins came in the second races at Diepholz and Brno.

In an interesting move, the 1991 season saw Soper two-timing by returning to race in the BTCC as well, finishing fourth in the title race. This scheme continued in 1992 when Steve raced the proven E30 M3 in Germany while debuting BMW’s new E36 318is in Britain, where the 2-litre foundations were being laid down for the Super Touring rules that would later spread across the continent. Soper’s part-time contract with the semi-works Vic Lee team allowed his home country to get re-acquainted with his spectacular, no-holds-barred style.

It probably became a tad too spectacular in the final round at Silverstone. Soper’s team mate Tim Harvey, Toyota’s Will Hoy and Vauxhall’s John Cleland were all still in with a chance of the title. With the field exploding with support drivers, including Soper, It all developed into somewhat of a slug match. First Soper and Leslie (Vauxhall) connected, leaving Robb Gravett (Peugeot) to smash into Soper’s BMW. Demoted to last place and his car’s back-end firmly demolished, Steve began a race to catch up. Setting an incredible pace, he caught up with the championship and profited from Harvey and Hoy knocking each other up to move up to fifth, with championship contender Cleland ahead of him in fourth, just enough for the Scot to be champion. Now riding shotgun for Harvey, Soper then also dealt with the Vauxhall. Cleland was left unimpressed, giving the Surrey man the finger after the pass. John would soon be fuming even more when Harvey also went past and was quickly allowed into fourth place, Soper now morphing into Harvey’s tailgunner. The following scenes were instant tin-top classics, as Cleland barged his way through on the BMW’s inside at Brooklands with Soper closing the door. Momentarily, the Vauxhall was on two wheels, leaning against the BMW, but when it became planted again it was ahead. Then, into Luffield, Soper retaliated by taking to the grass in his effort to regain the place. Instead, a game of billiards was the result, putting both cars out on the spot, enabling Harvey to cruise to fourth place and the championship. An outraged Cleland jumped from his car and looked set to attack his nemesis before deciding against it. He was later quoted as stating that Soper was “an animal”.

The BTCC outings possibly detracted from his DTM programme, as he only managed ninth in the 1992 rankings in the season that went all Klaus Ludwig’s way. Steve still won the first race of the AVUS weekend, though, and also added the second Norisring heat to his tally. The Spa 24 Hours produced a spectacular final few laps when, out of the Bus-Stop chicane, with just one minute to go, Soper muscled his Bastos-liveried Bigazzi BMW M3 past local hero Eric van de Poele’s FINA-sponsored Schnitzer example to claim an unexpected last-gasp win – by a mere one second! – in the Belgian traditional.

Putting one over the Schnitzer boys was rewarded with a full-time Schnitzer drive in the team’s 1993 BTCC programme, with Joachim Winkelhock as his team mate. The crack German outfit was sent across the North Sea when BMW GB decided to pull out of the BTCC, leaving its race team Prodrive to do the Subaru WRC programme, while Vic Lee Motorsport was liquidated in the wake of its team boss’s arrest on drug charges. At the zenith of Super Touring, BMW’s E36 faced serious opposition from all-comers, including Vauxhall, Toyota, Nissan, Peugeot and Renault, some of which had turned into thinly veiled works efforts. BMW responded with a works team of their own, and showed their E36 318i wasn’t half as uncompetitive as BMW GB feared. They started with a one-two at Silverstone, Soper ahead of Winkelhock, with Soper also winning the third round at Snetterton. The rest of spring and summer was all about Winkelhock, the German taking five wins on his way to an unassailable championship lead. Soper backed him up and finished second in the standings, way ahead of their nearest rival, Ford’s Paul Radisich.

Next stop Japan, as Soper took the identity of a gai-jin to race in the JTCC, claiming the title at his second attempt. Now into his forties, Soper followed BMW into a new arena: GT racing with the BMW-powered McLaren F1-GTR. In preparation for 1996 Le Mans edition, Soper and Bigazzi joined the BPR Global trail at the fourth round at Silverstone, where his team mate was none other than Nelson Piquet. The pair finished fourth, but it would have been a win if Bigazzi had put in some more fuel. Soper also grabbed pole for the occasion. At Le Mans itself, Soper was again the fastest of the McLarens, as he joined Jacques Laffite and Marc Duez to finish 11th overall. In the GT1 class, however, it was consummately outpaced by Porsche’s new 911 GT1.

When the BPR Global Series morphed into the FIA GT Championship in 1997, Schnitzer moved in to replace Bigazzi, and Soper joined a line-up of JJ Lehto (previously engaged with the GTC McLaren team), Peter Kox and Roberto Ravaglia. With Lehto, Steve fought valiantly against the powerful Schneider/Ludwig pairing in the equally powerful new Mercedes CLK-GTR. BMW look impressive in the first three rounds, when Soper/Lehto won twice at Hockenheim and Helsinki while Kox/Ravaglia took the spoils at Silverstone. Wins at Spa and Mugello kept Soper and Lehto in the championship lead as Bernd Schneider enjoyed a fruitful summer to close the distance. The two final overseas races proved disastrous, though. All looked well with pole at Sebring but an engine fire ten laps from the end put the McLaren out of the running, and gifted Schneider the championship lead. Then, Schneider and Ludwig won again at Laguna Seca, putting the issue beyond doubt. It was scant consolation for Soper that he won the Macau Giua race late in the year. Le Mans ended in a DNF for Soper/Lehto/Piquet while the sister car of Kox/Ravaglia/Hélary took third.

Soper in the Schnitzer-run BMW Motorsport McLaren F1-GTR at Donington Park in 1997 The race was won by Schneider/Wurz in their CLK-GTR, with Soper/Lehto finishing third. (photo Tony Harrison)

Now at a pristine 46 years of age, Soper was set for the new challenge of endurance racing – that is, even more enduring than the 4-hour races he had got used to in FIA GT. With the McLaren F1-GTR usurped by the CLK-GTR, especially in its unbeatable 1998 guise, BMW copped out of GT racing to step up to pukka Le Mans prototypes. This was a trade they had never practiced before, so they teamed up with their F1 partners Williams and had Indy constructor G-Force build the chassis. The result was the unspectacularly named V12 LM. Matched with Tom Kristensen and Hans Stuck, Soper bowed out of the 1998 Le Mans 24 Hours when a wheel bearing gave the ghost. To BMW’s frustration, it was proved to be a simultaneous defect since the sister car of Cecotto/Winkelhock/Martini had succumbed to the same fate only moments earlier. When the works efforts of Mercedes and Toyota also failed Porsche was the last one to laugh.

When Don Panoz started the American Le Mans Series in 1999, BMW found a platform to race its improved V12 LMR prototype regularly throughout the season. Dyson and Rafanelli entered their Riley & Scott MkIIIs, and Porsche brought its 911 GT1 Evo, to be run by Champion Racing. Ferrari 333SPs and Panoz’s impressive Reynard-built LMP-1 Roadster-S ‘Batmobile’ provided further variation. Steve rejoined Lehto and Kristensen for the Sebring 12 Hrs season opener and won first time out, beating the Dyson Riley & Scott-Ford driven by the classic ALMS trio of Weaver/Leitzinger/Forbes-Robinson. Soper would be paired to Lehto again for the rest of the season as they rejoined the championship in the fourth round at Sears Point. Steve duly won again, ahead of the Brabham/Bernard Panoz. At Portland, the Australian and the Frenchman turned the tables, and they repeated the trick in the Petit Le Mans at Atlanta, where Soper was joined by Joachim Winkelhock and Bill Auberlen. The final two rounds were Soper and Lehto’s again but it wasn’t enough, as Johnny O’Connell and Jan Magnussen did just enough to hand Panoz the inaugural LMP title by two points. The 1999 Le Mans result made up for all of that, of course, since Winkelhock, Martini and Yannick Dalmas managed to beat the Dallara-penned Toyota GT-One and the two Audi R8Rs (incidentally also Dallara-built!) to a popular victory for the all-white V12 LMR. Steve was added to the line-up of 1998-spec BMW V12 LM of Price + Bschr Racing, and co-driving with Auberlen and team boss Thomas Bschr finished fifth.

More ALMS followed in 2000 but now Audi had joined the fray. Soper teamed up with Auberlen and Jean-Marc Gounon for Sebring while Lehto was transferred to the Jörg Müller V12 LMR. The Audis had them covered, though, running away to a dominant one-two. Lehto/Müller and Gounon/Auberlen would be the ALMS season regulars and the former pair two took wins at Charlotte and Silverstone before Audi steamrollered the championship. For Soper it was time to consider retirement, but not before he had one last go at the BTCC. A surprise switch to Peugeot’s 406 Coupé saw him miss out on a win at Oulton Park, in his 100th BTCC start. His swansong race came at Macau in a Peugeot 306. A violent accident at Brands Hatch had been the clincher – it was time for ‘the greatest saloon car driver of all time’ to hang up his helmet.