Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park

Part 10: Penske PC23 - a home for the engine

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- December 4, 2009; with September 25, 2014 additions

Related articles

- March-Alfa Romeo 90CA - Fiasco Italo-Brittanico, by Henri Greuter

- March-Porsche 90P - The last oddball at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, by Henri Greuter

- Penske-Mercedes PC23-500I - Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park, by Henri Greuter

- Introduction

- Part 1: Penske Racing at Indianapolis - new standards

- Part 2: Ilmor Engineering at Indianapolis

- Part 3: Mercedes, Benz and Mercedes-Benz at Indianapolis up until 1993

- Part 4: Equivalency formulas - waiting for things to go wrong

- Part 5: Stock blocks - keeping them rolling and promoting 'Born in the USA' technology

- Part 6: Indianapolis 1991 - Chevy And Rich Team owners

- Part 7: The Speedway narrowed, its speeds lowered

- Part 8: The forerunner

- Part 9: Pre-May '94 plans

- Part 11: The 1994 Indycar season until mid-April

- Part 12: The unfair advantage and when others have it

- Part 13: Practice during the 1994 'Month of May'

- Part 14: Other bespoke-design 209s

- Part 15: From the last weekend of May '94 to the end of the season

- Part 16: Could the Mercedes Benz 500I have been stopped in time?

- Part 17: Creating an extinct species without it being forbidden, initially at least

- Part 18: The 1995 '500' - Did the Mercedosaurus bite its masters after all?

- Part 19: A possible twist of fate for Rahal-Hogan and Penske as a legacy of the 500I

- Part 20: Re-evaluation of our verdict

- Part 21: PC23's further active career after 1994

- Part 22: USAC’s points of views and some answers

- Part 23: The loose ends that didn’t fit in anywhere else and the epilogue

- Part 24: "Plan your work; work your plan" - Chuck Sprague on the PC23

- Appendix 1: Specifications

- Appendix 2: Car and driver appearances and performances during the Month of May 1994

- Appendix 3: Chassis, entry, practice and race numbers in 1994

- Appendix 4: PC23's 1994 results sans Mercedes Benz 500I

- Appendix 5: PC23's 1995-'96 results sans Mercedes Benz 500I

- Appendix 6: A reflection on the PC23 chassis used by Team Penske in 1994

- Appendix 7: A review of Beast by Jade Gurss

What?Penske PC23 chassis When?early 1994 |

|

Why?

Before giving attention to the main subject, the 1994 Penske PC23, it is appropriate to pay some attention to the predecessor, the 1993 type PC22-Chevy/C. Knowing more about the PC22 enables one to get a better understanding 'where the PC23 came from'.

After two frustrating seasons struggling with unsuccessful Alan Jenkins-designed Penske cars and customer March cars, Roger Penske recruited Nigel Bennett from Lola. Bennett's first design for Penske, the 1988 PC17, formed the foundation (the “Archfather”) for a series of evolutionary cars. The 1989 PC18 was an evolution of the PC17 and the 1990 PC19 was an update of the PC18. The most significant change on the PC19 was that the exhaust flow was no longer released at the center of the car, above the gearbox, but at the end of the left sidepod. And instead of a single wastegate near the turbo, each cylinder bank had its own wastegate, also venting off at the end of the sidepod. The 1991 PC20 was inspired by the 1990 PC19 and introduced a transverse gearbox. Yet another 'update', but still a descendant from the '88 PC17 was the 1992 type PC21-Chevy/B.

The 1993 car, the PC22-Chevy/C was the most radical departure from the basic concept with which designer Nigel Bennett had started back in 1988. We are running a bit ahead of things to come but to understand the significance of the '93 PC22 for Team Penske it is worth mentioning that it formed the basic concept that was refined over the years up until 1996. The ‘94, '95 and '96 Penske CART contenders can all be traced back to the 1993 concept.

The PC22 was a very good car, better than its records show and these are impressive already. Emerson Fittipaldi won three races with it, including Indianapolis. Teammate Paul Tracy did even better with five victories that year. Despite this, the drivers of Team Penske both had missed out on the CART title, in Fittipaldi's case by a few points. Some misfortune but also too many driver errors prohibited clinching the title. Nigel Mansell became champion instead, given the fact that he was a rookie within CART this was quite a surprise. Paul Tracy however can be excused to some degree since 1993 was his first full season in CART. In 1992 he had done a limited program as third Penske entry but eventually taking over when Rick Mears was forced to cut back his season due to injuries.

At Indianapolis the PC23 had not delivered an earthshaking performance during the first week of qualifying; Tracy had qualified 7th, Fittipaldi 9th. During the second weekend of practice, however, the team managed to sort out the cars properly, not in the least because of the valuable assistance of the retired Rick Mears who served as a consultant for the team. On race day, Fittipaldi in particular had a car that was a real threat when it really mattered: the final stages. Having worked his way to the front, he was able to make his move for the lead with 16 laps to go and remained there to take his second '500' victory. Curiously, this was the only victory on an oval track for the PC22-Chevy/C.

The 1993 Penske PC22 had been a very good tool that season with only minor shortcomings, the most obvious one to see the lack of being able to win on short ovals.

Rule changes ordered for the 1994 season made smaller rear wings on the short ovals mandatory and Team Penske put in a lot of test efforts to minimize the effects of these rule changes. In fact, one of the priorities within the design was to find the most aerodynamic efficiency on the shorter ovals. Some work on the transmission was done as well. Other than that, the new car was very much based on the successful predecessor. There had been plans to fit the PC23 with a mechanical active suspension system but this plan had to be shelved due to a ban by CART on such technology.

The resulting chassis itself was therefore not as revolutionary for CART standards as it could have been. However, it was an example of evolution improving a good concept into an even better one, designed to offer the option to become revolutionary for one, specific race. The most important one in which it had to compete.

It was the policy of Team Penske to have a new car for next season ready before Christmas the previous year in order to run the car early on at both Firebird and the Phoenix oval. The new Ilmor 265D was also ready for being tested from mid December on in the new for 1994 PC23.

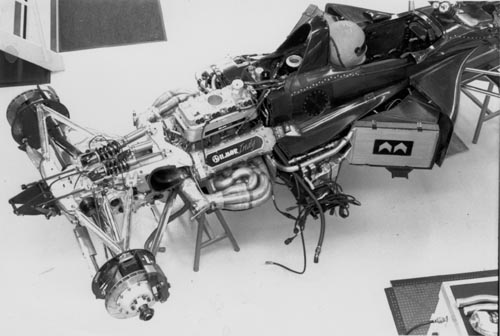

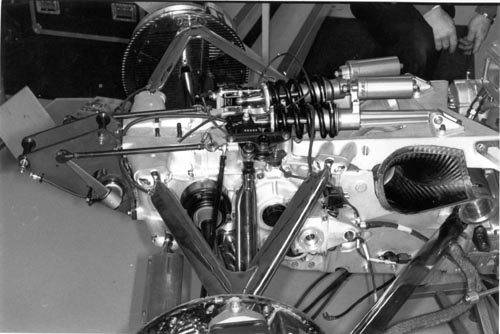

This is one of the PC23 cars fitted with an Ilmor/D, built up at the factory. These pictures were taken in December 1993 by Tony Matthews and he used them to create the cutaway drawing he made of the car. (photos copyright by Tony Matthews, used with permission)

About the Indianapolis version of the PC23

The most obvious part was a new engine cover, required because of the much higher engine. The people at the factory who had to make these parts were told that it was something related with Indianapolis but no details as of why. But the people at the factory were used to making special parts for Indianapolis.

A less visible but obvious modification was a much stronger gearbox, to cope with the higher power and torque the pushrod engine provided. Geoff Ferris took care of the design of the gearbox. At that time the engine was internally known as the 265E or the E. Since the E turned lower RPMs, the gearing in the box had to be different too. The gearbox for the E engine used a different drop gear ratio. The E box had a 27:22 ratio, the D box had a 26:23 ratio. This enabled the use of the same final drive ratio and gear ratio selection for both boxes.

Despite being stronger, the two gearboxes were of approximately the same weight, thus causing only a minor shift in the weight balance if such was noticeable.

The E engine was slightly lighter then the Ilmor 265D, although because of its longer inlets the center of gravity of the entire engine was higher than that of the D, thus changing the overall balance of the car a bit.

The car was not heavily modified in order to increase the corner speeds. One could almost say that for using the Ilmor 265E the PC23 was adapted for, but not perfected to make the most out of what the 265E engine could provide.

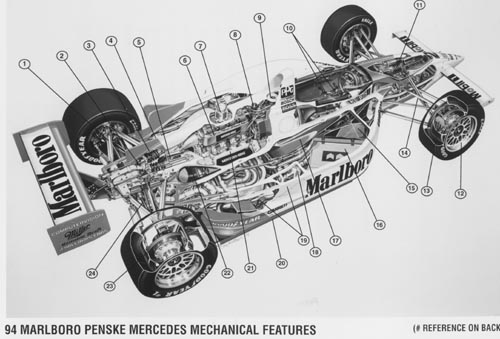

This cutaway drawing of the Penske PC23-500I was included in the Team Marlboro media kit, released at Indianapolis. Tony Matthews made it and how that came about is a story in itself.

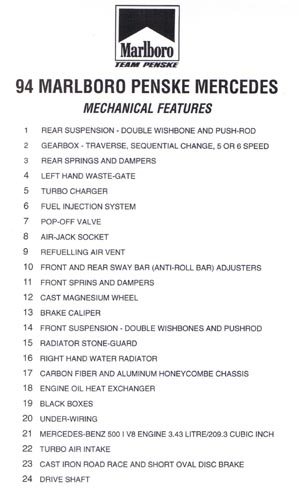

The backside of the picture had the legend for the numbers on the picture above.

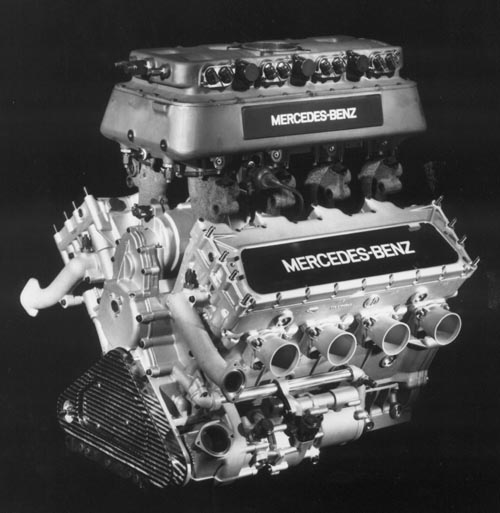

This was the only picture of the engine included in the Mercedes press kit as released at Indianapolis that May. The picture could also be found in the media kit about the 1994 Louis Schwitzer Award released by the Society of Automotive Engineers.

The first tests

The first tests with a 265E engine took place at the end of January '94. Even that happened in the utmost secrecy. Penske's US workshop was located in Reading, PA. Adjacent to the building there was another business building, owned by Penske Truck Leasing. A very small group of engine engineers led by Kevin Walter built a completely separate, secret workshop (known as the “Taj Mahal”) in one of the buildings on the terrain. The engines were built up there. Testing them on the dyno however was done in secret in the main building during the night. The engines were run until they broke so the weak points were discovered. The employees who arrived in the morning found out to their surprise that the water of the dynomometer was still warm.

One month later the first tests with an engine installed in a car took place, at the Nazareth Speedway, owned by Roger Penske. At that time the project was still carried out in the utmost secrecy but now there was the risk of the secret coming out. The Andretti family lived in Nazareth and if by chance Mario found out about the tests at the track and heard the engine noise, he might understand what was going on. Fortunately for Penske and Ilmor, Mario was out skiing.

Addition made in September 2014: Nigel Bennett and Jade Gurss, respective authors of the books Inspired to design and Beast, both end the legend that Mario Andretti never found out anthing about the secret tests at Nazareth. Both say Andretti eventually confessed he heard the noises from the track and realized something secret was going on, although he didn't link those with an Indycar project. Thus so much for Ilmor and Penske's luck that Andretti was skiing that winter when they were testing. Nevertheless, there was one strike of fortune for both Ilmor and Penske with regards to Mario. Although he had heard the tests and was aware of something happening at Nazareth Speedway, Andretti pretty much shrugged it off and didn't give it any further thought. One could say that Andretti heard the alarm bells ringing, yet ignored them.

The PC23 was by that time already sorted out in its regular version, powered by the Ilmor 265D. The test team had at least a chassis at its disposal that was fairly well known. All tests with the 265E pushrod thus could be carried out with the car that was going to use it.

Paul Tracy carried out the tests on Nazareth in nasty conditions. It was winter and Pennsylvanian winters can be severe. So was the winter of 1994.

Addition made in September 2014: In his book Beast, author Jade Gurss reveils that although it is the better known fact that Paul Tracy carried out most of the tests in Nazareth in the winter of 1994, it was Al Unser Jr who made the first miles onboard of the 265E-powered PC23-004 'mule'. He did two days of testing in a three-day period before Paul Tracy took over.

The tests were carried out under the direction of the newly assigned engineering manager Grant Newbury. Newbury had been Fittipaldi's race engineer but took a kind of supervising position for 1994 and was no longer assigned to work with a particular driver. The track was covered in snow so snow ploughs were out to make the track accessible. Tracy's engineer Nigel Beresford recalled that the snow itself was piled up in the pit lane and reached such a height that, when standing in the pits, it was impossible to see the car running unless you climbed up that mountain of snow. Apart from the snow, it was so cold that Paul had to wear a bulky ski suit in order to remain running. His running time was limited to runs of 20 minutes or so before he had to quit since he had become too cold to continue. The team ran the engine till it broke, brought the car back to the shop in Reading (one hour away), tore the engine down and reported what had broken to Ilmor in England.

Other than at Nazareth, another Penske-owned track was used to test the engine. The high-speed banked Michigan oval also saw numerous tests being carried out with the engine.

A lot of work was carried out those first months of the year to make the Ilmor 265E durable enough to endure a 500-miles race. And all of this work was carried out in the utmost secrecy, both in the USA by the Penske team members as well as at the Ilmor factory in England. The men in charge on both continents had assured that their staff wouldn't say a thing to anyone. In America, this was one of the things that Roger Penske had done himself. Crew member Nigel Beresford told the following about how Roger told his staff about the existence of the E.

“Once the project reached the point where the engine had to go in the car then Roger came to the workshop in Reading to talk to the whole team – this was not something he did very frequently because he relied heavily on Chuck Sprague, Clive Howell and Karl Kainhofer to run the team and execute his directions while he concentrated on building the corporation. Roger gathered everybody together in the small dining area and talked about the importance of maintaining the secret. He warned everyone that if the secret got out then it would be like “cutting your pay check in half” – i.e. everyone would stand to benefit well if the project was a success (i.e. we won Indy) but we would all lose a lot if it got banned.”

Apart from the engine the gearbox could also be rated as a, to some extent, new component. Initially the box had some reliability problems with the bevel gears that were used to transfer the torque.

The majority of the test work had been done by Tracy and Al Unser Jr. Emerson Fittipaldi lived in Florida and needed time for his business enterprises. Paul Tracy on the other hand lived closer to Nazareth and Michigan. He was also pretty much the youngster within the team, the team mate of the two most recent winners at Indianapolis. A lot of the test work was simply running laps. Given his junior status as well as yet more chance to get track time Paul was assigned to most of the running sessions with the 265E-engined test car. But although the job came to him given his position in the team, he acquitted himself admirably with the work at hand and his work was praised by the engineers.

Addition made in September 2014: For more details on the PC23 I recommend the book Inspired to design by Nigel Bennett. For more details about the development of the 265E I recommend the book Beast by Jade Gurss.