Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park

Part 3: Mercedes, Benz and Mercedes-Benz at Indianapolis up until 1993

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- September 22, 2009; updated December 13, 2012

Related articles

- March-Alfa Romeo 90CA - Fiasco Italo-Brittanico, by Henri Greuter

- March-Porsche 90P - The last oddball at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, by Henri Greuter

- Penske-Mercedes PC23-500I - Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park, by Henri Greuter

- Introduction

- Part 1: Penske Racing at Indianapolis - new standards

- Part 2: Ilmor Engineering at Indianapolis

- Part 4: Equivalency formulas - waiting for things to go wrong

- Part 5: Stock blocks - keeping them rolling and promoting 'Born in the USA' technology

- Part 6: Indianapolis 1991 - Chevy And Rich Team owners

- Part 7: The Speedway narrowed, its speeds lowered

- Part 8: The forerunner

- Part 9: Pre-May '94 plans

- Part 10: Penske PC23 - a home for the engine

- Part 11: The 1994 Indycar season until mid-April

- Part 12: The unfair advantage and when others have it

- Part 13: Practice during the 1994 'Month of May'

- Part 14: Other bespoke-design 209s

- Part 15: From the last weekend of May '94 to the end of the season

- Part 16: Could the Mercedes Benz 500I have been stopped in time?

- Part 17: Creating an extinct species without it being forbidden, initially at least

- Part 18: The 1995 '500' - Did the Mercedosaurus bite its masters after all?

- Part 19: A possible twist of fate for Rahal-Hogan and Penske as a legacy of the 500I

- Part 20: Re-evaluation of our verdict

- Part 21: PC23's further active career after 1994

- Part 22: USAC’s points of views and some answers

- Part 23: The loose ends that didn’t fit in anywhere else and the epilogue

- Part 24: "Plan your work; work your plan" - Chuck Sprague on the PC23

- Appendix 1: Specifications

- Appendix 2: Car and driver appearances and performances during the Month of May 1994

- Appendix 3: Chassis, entry, practice and race numbers in 1994

- Appendix 4: PC23's 1994 results sans Mercedes Benz 500I

- Appendix 5: PC23's 1995-'96 results sans Mercedes Benz 500I

- Appendix 6: A reflection on the PC23 chassis used by Team Penske in 1994

- Appendix 7: A review of Beast by Jade Gurss

Who?Ralph de Palma, Rupert Jeffkins What?Mercedes 140 'The Grey Ghost' Where?Indianapolis When?1912 Indianapolis 500 (picture courtesy of IMS) |

|

Why?

Mercedes Benz has been represented at Indianapolis ever since the very first '500', although this happened by the two companies separately since they were still independent at the time. Mercedes, Benz and/or Mercedes Benz haven't been regulars at the Speedway but nevertheless their cars were involved in some of the most historic events at the track. They also put their names in the record books as the first to bring a certain piece of technology to the Speedway.

In 1911 it was Spencer Wishart who finished 4th with a Mercedes 140. Two Benz cars, driven by Billy Knipper and Bob Burman, also started the event and were classified 18th and 19th respectively.

Wishart was back one year later with his Mercedes but this time he retired before the halfway point and was classified 15th. And had the second Mercedes in the race that year been the only ever Mercedes in any 500-miles race, the name of Mercedes would have remained legendary,

Ralph de Palma drove a slightly modified Mercedes 140 (a 1908 GP car) nicknamed 'The Grey Ghost' in the 1912 race. In lap 3 he took the lead and lapped the entire field at least once up until his 196th lap. Then a connecting rod in the engine broke, slowing De Palma down but the wrecked engine cried enough in De Palma’s 199th lap, as the car came to a standstill in turn four. Together with his riding mechanic Rupert Jeffkins, De Palma pushed the car to the finish to be credited with 199 laps, eventually classified as 11th. No less then 196 of his 199 laps he had led the race and still he lost it and, because of having failed to complete the distance, he didn’t get a dime of the price money. Only the top-10 cars were eligible for prize money and only as long as they had driven the entire distance. Which, in the case of the 10th place finisher had taken almost 9 hours!

De Palma’s lost race of 1912 was one of the legendary moments in the history of the '500', not the least for the gracious manner in how De Palma accepted his cruel fate. Ever since 1912, De Palma had been the all-time leader in leading most laps. He remained so until Al Unser Sr curiously enough equalled De Palma's record ij 1987 and eventually broke it one year later.

Seen in 1988 and 1990 in the collection of the IMS Museum, a Mercedes said to be the car driven by Ralph de Palma in 1912. Perhaps an even more legendary car than the Mercedes de Palma used to win the race three years later. (photos HG)

De Palma’s 1912 race caused two records to be written that still stand to this day. No other driver has led the race for 196 laps without winning it. Secondly, no other driver than 1912 winner Joe Dawson has ever won the race by leading such a small amount of laps. The only two laps he led during the entire race were the last two!

Belgian Theodore Pilette drove a Mercedes chassis powered by a Knight engine to fifth place in 1913, a respectable result given the fact the car had the smallest engine of the field. The lone 100% Mercedes car that year was 'The Grey Ghost' driven by Ralph Mulford, who was classified 7th after losing much time when he ran out of fuel. One year later Mulford finished 11th with the same car.

In 1915 it was almost 1912 all over again. Ralph de Palma was back at the Speedway and adding up to his tally of laps in the lead, again driving a Mercedes GP car, this time the 4.5-litre 1914 model that had won the epic GP of France that year. And again, with just three laps to go the engine broke a connecting rod! This time, however, Ralph managed to nurse his wrecked engine to the finish line and win his well-deserved '500', still in a record speed average. It was to remain De Palma’s only '500' victory ever but he could so easily have won at least three more during his fine career.

In 1923 Mercedes wrote another kind of history at the Speedway. During World War I, the company had gained valuable experience making superchargers work on airplane engines. The technology was promising enough to gain additional power from racing engines. The engine formula at Indianapolis at that time was for 2-litre engines, having gone down from 3-litre in order to reduce the speeds a bit. Supercharging appeared to be a suitable method to reclaim some of the power. At that time the knowledge about supercharging and the gains it provided was still so small that the rule makers of those days didn’t see it as an advantage over non-supercharged engines and required some kind of equivalency formula. Anyone who wanted to use a supercharger was free to put it on its engine and take the risk of the device being the cause of retirement…

Mercedes was among the pioneers in using supercharged engines on racing cars. In 1923 they entered three supercharged cars at Indianapolis. These were generally accepted to be the first-ever blown cars entered and raced in the '500'. They were not, however, the first supercharged cars ever at the Speedway. That honour went to one of the blown Chadwick 'Great Sixes' that ran in one of the 1909 events.

The three Mercedes cars were driven by Karl Sailer, Christian Lautenschlager and Christan Werner. Sailer finished in 8th place, Werner ran as high as third for a while but was classified 11th, last of the cars that made it to the finish with the entire race distance covered.

A remarkable detail about this 1923 effort is that it's the only time until 1994 that the Mercedes factory was officially involved in an Indianapolis enterprise. All previous attempts had been with privately entered cars.

One year later it was Ora Haibe who started in the '500' with a privately owned Mercedes car, classified 15th after having started 17th. His car was one of the previously raced factory cars which was sold off instead of shipped home to Germany.

According to Karl Ludvigsen’s splendid book Quicksilver Century Mercedes had been close to sending at a team to Indianapolis in 1938 but eventually it didn't come so far after all.

It would take more than 20 years after Haibe’s 1924 race before another Mercedes car appeared at the Speedway. But if you want to talk about a car that appeared at Indianapolis with a reputation and high expectations, it was this car.

During the war Mercedes had hidden a number of its racing cars all over Germany and occupied Eastern Europe. One of these was a 1939 W154-type Grand Prix car fitted with a M163 V12 engine, chassis W154/9. This car was discovered in Czechoslovakia. It went to England but it was eventually sold to American Don Lee. Lee had a reputation at Indianapolis for entering exotic (read European) racing cars for the '500'. Back in 1938 the rules at Indianapolis had been changed in order to attract the European top teams. But other than some privately owned Maseratis and Alfa Romeos none of it happened. But at long last, one of the invincible German-built supercars was to appear at the Speedway, be it as a private entry. The Don Lee team entered the car for 1947 with Duke Nalon as its driver.

Duke Nalon in the Don Lee Mercedes W154 (picture courtesy of IMS)

When doing research on the Novi legend I had the privilege of interviewing Duke Nalon on several occasions, be it on long afternoons or just a short chat about a detail. During one of our long afternoon talks the year with the Mercedes came up for discussion as well.

1947 was marred by the dispute between the ASPAR-organized drivers demanding a higher percentage of gate income and the Speedway management who refused to give in. Duke was in sympathy with ASPAR’s demands but did not join them in their boycott of the Speedway. He realized all too well that he had one of the potentially fastest and best cars ever entered at the Speedway to his disposal and joining ASPAR meant that he was going to lose the ride. He couldn't bring himself to giving up the car that could well be his best-ever chance of winning the 500.

Nalon recalled the car was comfortable, the seat fitted him well. The backside of the seat was marked 'Von Brauchitsch'. Duke stated that “It was the most comfortable race car I ever drove. It had comfort to it and it had three-position shock absorbers. When you had a full load of fuel, you had 42 gallons in the cowl and about 45 gallons back here. And you had to take the steering wheel out to get in and out.”

Preparing the engine had been a challenge. Duke recalled that Riley Brett, the famous mechanic who worked with Offenhauser, somehow had obtained the blueprints of the 91 CI (1.5-litre) Mercedes V8 engine that ran at Tripoli. (That must have been the 1.5-litre M165 engine.) Using these drawings, the team could prepare the car and sort out all the oil and other linings. Duke got the prints from Brett and chased parts for getting the work done. Using the drawings for guidance, the mechanics sorted out the oil lines on the engine and eventually got the engine ready for running. Duke was told: “You gonna be here in the morning because we’re gonna fire up the car.“

When Duke did arrive the following morning, car and engine were taken apart…

Tommy Lee, the owner of the car, came in at night and had said to his crew that if they could fire up the car next morning they could do it now as well. So they fired the car up and had the engine idling, instead of revving it up every now and then. As a result, the fuel condensed in the manifold. Since the engine was canted in the frame the rear end of the engine sat lower in the car than the front part so rear cylinders were loading up with raw fuel, and it hydraulized the rear cylinders, breaking the rods and one piston.

New connection rods were made, but replacing the well-balanced forged piston was another matter. Eventually the team could get a sand cast replacement piston and Duke was able to qualify the Mercedes later in the month. Duke qualified 18th but showed the car's speed by setting the second fastest qualifying speed. Only Bill Holland in one of the FWD Blue Crowns had been faster.

The car couldn't live up to the expectations on Race Day, Nalon retiring after 119 laps with piston failure. And yes, it had been the replacement piston that failed.

Duke was all too aware of the fact of Mercedes cars requiring a massive staff of mechanics to get the most out of them, having seen the Mercedes team in action, and driven against them in the pre-war Vanderbilt Cup races at Roosevelt Field. The Don Lee team only had a single civil engineer working on the car, a man who had hotrods for hobby.

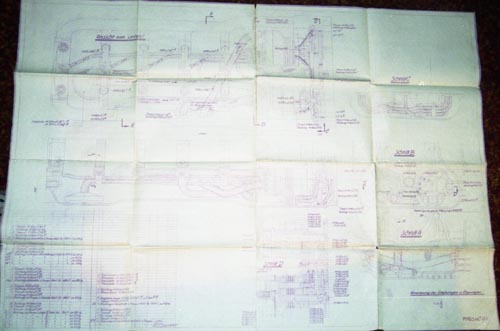

I'm not permitted to tell where and when I saw these drawings. But it was in the USA and they are told to be some of the drawings used by the Don Lee team to prepare the Mercedes engine. The M154 marking, however, identifies them M154 V12 drawings, so these can't be the M165 V8 drawings that Duke Nalon told about. So is this another set of drawings or was Duke mistaken? Given my experience with Duke I find it difficult to believe he was mistaken about the contents of Brett's papers he talked about… (photos HG)

Duke had obviously not lived up to Lee's expectation because he wasn't hired for the car next year. Instead the car went to Ralph Hepburn, the driver who had been ASPAR's president the year before and as a result had lost the ride in Lew Welch’s Novi, the car in which he set the track records in 1946. Hepburn had remained without a drive in 1947 but for 1949 he was to be back an a 450+ hp car. But he never qualified or raced the Mercedes.

Lew Welch had assigned his two Novis to Cliff Bergere and Chet Miller but both men had difficulties with the temperamental brutes. With Pole Day coming up, Cliff Bergere had yet another spin and damaged his car slightly. He claimed a technical malfunction having caused the spin but chief engineer Bud Winfield felt it impossible that given the Novi's specifications an accident like Bergere's could have taken place. It remains a matter of who you want to believe to decide whether Cliff Bergere left the team (as he told) or was fired (as some Novi team members that year said).

In need for a driver able to tame his monster car, Lew Welch offered the Novi to Hepburn again and 'Hep' was unable to resist a return to the car he had called 'his baby'. What happened is history: Hepburn did sort out the car during the practice session that took place in between qualifying but didn’t qualify. The following day, when the car was converted to the setup he ran in 1946, Hepburn was killed in a fierce accident during a practice run.

More misery for the Novi team came when Chet Miller had informed Lew Welch he wanted to be released from his contract since he couldn't get on terms with the Novi. Welch respected the decision and let Miller go. Chet ended up in the Don Lee Mercedes. He qualified in the middle of the field, without any earth-shattering speed but had to retire with oil problems on Race Day after 108 laps. He was classified 20th. The Novi vacated by Miller was taken over by Duke Nalon.

The Mercedes, great car as it was, was the wrong car at the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong team. It was too complicated for the Don Lee team. To extract the maximum results the car needed the attention of factory mechanics. But even they would have had a hard time making the car work reliably on a track unlike anything else the V12 had ever been used on.

The Don Lee Mercedes holds one curious distinction. In the two years it ran it was involved in the careers of the three most famous drivers of the FWD Novis. Duke Nalon and Chet Miller actually drove the Mercedes in the race while Ralph Hepburn never got that far.

For 1949 the Mercedes was sold off. It went into the possession of eccentric millionaire team owner Joel Thorne. Thorne had the mighty (complicated) Mercedes V12 engine taken out and replaced it with one of his exclusive Sparks Straight Six engines. The bonnet of the car didn’t fit anymore so a new one was made, making the car look downright horrible. Thorne drove it himself but failed to qualify the mutilated car. How must Alfred Neubauer have felt when he saw it?

Neubauer was present at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1949 in order to study the possibility of a works Mercedes effort. The factory had recovered some of their pre-war cars although these were no longer suitable for Grand Prix racing. That category was now for 4.5-litre non-supercharged or 1.5-litre supercharged engines. But Indianapolis still permitted the use of 3-litre supercharged engines so the old W154 cars were still eligible for the Speedway.

Neubauer spent some time with what was one of the two most professional teams at Indianapolis, Lew Welch’s Novi team, after which work was undertaken to adopt the W154 to high-speed oval racing and be ready in time for the 1951 race. W154s ran in Argentina that year but failed to make a decent impression, leading to the plans of driving at Indianapolis to be called off.

According to Karl Ludvigsen's Quicksilver Century Mercedes undertook one surprising effort in 1956, Yes, that's after the company's racing program was brought to an end in the wake of the Le Mans nightmare when Mercedes left the sport on top as World Champions in both sportscars and Grand Prix racing. During 1956 studies were carried out to see whether a Formula 1 streamliner fitted with the 3-litre straight-eight sportscar engine had a chance of being competitive at Indianapolis in 1957. After extensive study, the plan was called off, however. It didn’t mean a lack of Mercedes participation at Indianapolis in 1957, since one obscure sighting of a Mercedes at Indianapolis must be listed: W154/9 made one final appearance at the Speedway as late as 1957! The old ex-Lee, ex-Thorne chassis had ended up in the hands of Edward Shreve, who entered it as the #84 Safety Auto Glass Special, driven by Danny Kladis. The engine bay, which had been filled by a straight-six in 1949, was occupied by another straight-six. This time, however. the car was powered by a Jaguar engine…

Driver Danny Kladis was a very colourful figure in IMS history with a record for which few will envy him. He qualified for his first '500' in his rookie year 1946 in a Granatelli Brothers-prepared Miller-Ford and was classified 21st in that event. He had no rides in 1947 to 1949 and in 1953. The remaining years up until 1957 he failed to qualify! 1957 was to be Kladis’ last year in which he participated as a driver at the Speedway.

Danny was asked about his 1957 adventures and some of his comments were included in the Day-by-Day report dated May 8th. It read as follows:

“I practiced it but it wouldn’t go, I’d shift coming out of #4 to get up speed, then I had to downshift it going into #1. I was so busy, it was crazy. It had about 50 levers in it to jack weight (actually four, one for each wheel). It was a formula one car with a five speed transmission. I don’t think anybody ever put it in fifth gear. They’d need a mile run to do it.”

Given the circumstances such as the age of the chassis, the engine that was used and the driver's previous record, it is almost needless to say that the car failed to qualify.

And that was, for the time being, the end of any Mercedes involvement in the history of the Indianapolis 500.

Another legendary Silberpfeil and how it almost lost some of its legendary status

The organizers of the prestigious Tripoli Grand Prix were so fed up by the string of victories by German-built cars since 1934 that they decided on a rule change for their 1939 event. In the Grand Prix category, the Italian opposition of primarily Alfa Romeo and Maserati had been overwhelmed by the German teams, but in the voiturette category, the Formula 2 of its days, there was no German representation. The Italians had that category, which called for supercharged 1500cc engines, all for themselves. By organizing the 1939 race for voiturettes instead, the organizers counted on an Italian-built winner as apart from Tripoli all major Italian events for single-seaters were held for voiturettes.

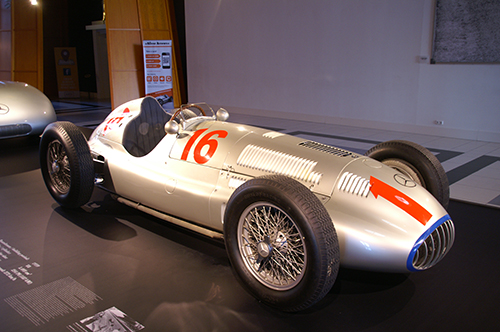

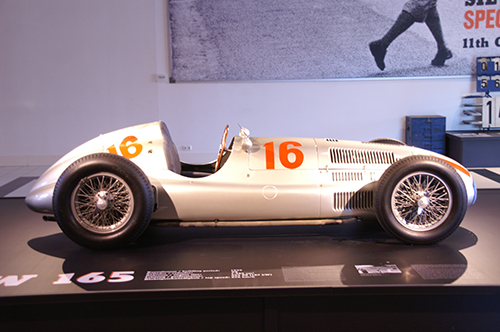

However, both Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union undertook the effort to build a new 1.5-litre car in order to participate in the event after all. It must be pointed out that maybe nowadays Monaco is rated as the most glamorous and prestigious GP but in the pre-war years Tripoli was the glamour event on the calendar. The Auto Union never made it but Mercedes managed to have their car designed and built in eight months' time. The engine was a supercharged V8 designated M165 and built into the car named W165. Two cars were built and tested and sent to Tripoli to be driven by Herrmann Lang and Rudolf Caracciola.

Although virtually brand new, the two Mercedes cars had the legs on the entire Italian-built opposition and scored a convincing 1-2 victory, humiliating the Italian cars in the process. For a multitude of reasons, neither of the two W165s was used in other events that year, even though development on them did take place with the eye on the future. That future was cut short when war broke out. The two cars were hidden near Dresden.

Mercedes driver Rudolf Caracciola and his wife Alice Hoffmann already lived in Switzerland before World War II broke out and remained there during the war. Caracciola then contacted the Board of Mercedes during 1941 with the suggestion to give him one of the W165s as compensation for not being fully paid his salary and other incomes. Mercedes was willing to cooperate but getting the cars out of Germany was a near impossibility. But somehow (and the men behind that must have had a story worth telling!) some Mercedes employers managed to get both cars to Zürich, Switzerland and delivered them to the local Mercedes importer. Being German property, however, the cars were immediately impounded by the authorities. After a number of events (more on those later) Caracciola went to court in Switzerland to re-claim the cars but he lost the case. Instead, the cars were put up for sale. Eventually, the Swiss Mercedes Benz importer turned out to be the highest bidder and thus saved the cars for the company.

After the war, when Mercedes was ready to do some racing again with the pre-war cars they still had left, plans arose to revive the W165s by building new cars, all of this taking place in 1951. By that time, however, it became clear to Mercedes race director Alfred Neubauer that the highly supercharged 1.5-litre F1 cars were fighting a losing battle against the unblown 4.5-litre cars. When the Grand Prix formula adopted 2-litre unsupercharged engines instead, any future for the existing W165s or its newly built descendants was gone.

And so the Mercedes W165 went into the history books with a remarkable record. There are more brand new engines and cars that won their first-ever race but that hasn't happened very often in important racing formulae at (World) Championship level. The 1967 Lotus-Cosworth DFV was another but it didn't take a double victory.

But even rarer is the feat that a brand new car wins its first race, only to never race again anywhere in whichever event. It would take until 1994 before that happened again when the main subject of this series of articles performed the same feat. The curious detail about this 1994 car is of course the fact that although Mercedes had nothing to do with the design and manufacturing of the engine, it's still officially known as a Mercedes-Benz. And as with its 1939 predecessor, it was a blown V8 engine.

But there is another reason why this story is told here.

Even though the cars were impounded, Rudolf Caracciola received an invitation by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in early 1946 to try and qualify for the upcoming 500-miles race! Caracciola managed to get temporary possession of the car and together with some helping hands he got the car up-and-running and ready to be shipped to the USA. The Mercedes factory had nothing to do with this effort. The temporary release, however, didn't allow for the car to get out of the country. This ended the plan to run the car at Indianapolis. Which surely would have ended the car's unique status as the winner in the only race in which it ever competed.

Caracciola went to Indianapolis after all in order to acquaint himself with his options for the following year. He was then hired by millionaire Joel Thorne to drive one of his cars. During a practice accident he was injured gravely and needed to stay in the USA to recover. He and his wife became the guests of the new track owner Anton Hulman and his wife. This cemented a friendship between the Caracciolas and the Hulmans of which the evidence still can be seen at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum.

After Rudy's death in 1958, his collection of trophies and prizes was donated to the museum and put on permanent display. I am pretty sure that a number of European race fans with interest for the Silberpfeile era will regret they must travel to the USA in the knowledge that the very same IMS Museum gets so many visitors who couldn't care less about the trophy collection of a driver whose name doesn't mean anything to them.

It is speculative, of course, but it remains an interesting question: how different would things would have been if Caracciola had been permitted to bring the W165 to Indianapolis? Eventually, his trophies went instead and as a result will remain there forever. Here they are, on display in two cabinets of the IMS Museum. (photos HG)

As for the fate of the two W165 cars, eventually they went back to the Mercedes museum. One of them is in running condition and occasionally appears on car meetings. In late 2012 the car was part of a factory-supported exposition of Silberpfeile in the Dutch Louwman Museum. If the Tripoli track at Mellaha would still exist there is a good chance that the historic relevance of the W165's achievements would be even better understood and appreciated.

The Mercedes-Benz W165 on display in the Louwman Museum, The Hague, The Netherlands, December 2012. (photos HG)

For more detailed information about these Mercedes racing cars and the story about the W165 that almost went to Indy I recommend Karl Ludvigsen's Quicksilver Century and Rudolf Caracciola's biography Meine Welt.