Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park

Part 5: Stock blocks - keeping them rolling and promoting 'Born in the USA' technology

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- September 22, 2009; updated May 24, 2012, and July 28, 2012; with September 25, 2014 additions

Related articles

- March-Alfa Romeo 90CA - Fiasco Italo-Brittanico, by Henri Greuter

- March-Porsche 90P - The last oddball at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, by Henri Greuter

- Penske-Mercedes PC23-500I - Mercedosaurus Rex at Indianapolic Park, by Henri Greuter

- Introduction

- Part 1: Penske Racing at Indianapolis - new standards

- Part 2: Ilmor Engineering at Indianapolis

- Part 3: Mercedes, Benz and Mercedes-Benz at Indianapolis up until 1993

- Part 4: Equivalency formulas - waiting for things to go wrong

- Part 6: Indianapolis 1991 - Chevy And Rich Team owners

- Part 7: The Speedway narrowed, its speeds lowered

- Part 8: The forerunner

- Part 9: Pre-May '94 plans

- Part 10: Penske PC23 - a home for the engine

- Part 11: The 1994 Indycar season until mid-April

- Part 12: The unfair advantage and when others have it

- Part 13: Practice during the 1994 'Month of May'

- Part 14: Other bespoke-design 209s

- Part 15: From the last weekend of May '94 to the end of the season

- Part 16: Could the Mercedes Benz 500I have been stopped in time?

- Part 17: Creating an extinct species without it being forbidden, initially at least

- Part 18: The 1995 '500' - Did the Mercedosaurus bite its masters after all?

- Part 19: A possible twist of fate for Rahal-Hogan and Penske as a legacy of the 500I

- Part 20: Re-evaluation of our verdict

- Part 21: PC23's further active career after 1994

- Part 22: USAC’s points of views and some answers

- Part 23: The loose ends that didn’t fit in anywhere else and the epilogue

- Part 24: "Plan your work; work your plan" - Chuck Sprague on the PC23

- Appendix 1: Specifications

- Appendix 2: Car and driver appearances and performances during the Month of May 1994

- Appendix 3: Chassis, entry, practice and race numbers in 1994

- Appendix 4: PC23's 1994 results sans Mercedes Benz 500I

- Appendix 5: PC23's 1995-'96 results sans Mercedes Benz 500I

- Appendix 6: A reflection on the PC23 chassis used by Team Penske in 1994

- Appendix 7: A review of Beast by Jade Gurss

Who?Jim Crawford What?Lola-Buick T89/01 Where?Indianapolis When?1990 Indianapolis 500 |

|

Why?

If we need to discuss the subject of stock blocks at Indianapolis…

Well, their use started way back in 1911. The majority of the participating cars in the very first 500-miles race were stripped and hopped-up production cars with production based engines.

Stock blocks never had a prominent role in Indianapolis history compared to other varieties of US racing where their share was - and is - more substantial if not outright dominant. But the Ilmor 265E found its origins in their presence.

The subject of stock blocks at Indianapolis is too extensive to be discussed in a single part. So the story is broken up in smaller pieces, each focusing on one main topic. It's not that everything in these articles is of importance to the Penske-Mercedes PC23 but I think a decent overview of the history of stock blocks at Indianapolis is justified in order to understand why these engines are so important to Indy and how it eventually led to the PC23-500I becoming a reality.

So the stock-block factor is divided into four sections:

- The first decades and the normally aspirated engines up to 1994

- The earliest blown and turbocharged projects

- The first years of the Buick era

- How the genie was bottled and corked

The first decades and the normally aspirated engines up to 1994

As we said, the use of stock blocks at Indianapolis started way back in 1911. But in the late tens and the twenties they stood no chance against the overhead camshaft racing engines. However, in the late twenties, the years of the board tracks, racing the high-tech 1.5-litre (91CI) supercharged Millers and Duesenbergs had become high-speed processions in which overtaking rarely took place. Moreover, the jewelish cars were out of reach financially to everyone but the very wealthy. Sanctioning body AAA decided to open up competition by restricting the cars and outlawing all high-tech including supercharging and four valves per cylinder. Two-man cars were prescribed, and engines simplified while the maximum capacity was enlarged to 6 litres (366 CI). The majority of production engines qualified for this.

In racing history, these rules became known as the 'Junk formula'. Many believe these rules outlawing the glorious Miller 91s were a result of the depression that started in October 1929 but that's not the case. The Junk formula was already agreed upon before the stock-market crash happened. As if AAA knew what was to come…

So with the arrival of the Great Depression the racing world was at least prepared. Despite the limited finances, the starting fields grew to numbers of over 30 cars again. But it came with a price: more cars, each with two men on board, meant that the thirties became the bloodiest, most lethal era at the Speedway.

Although rules allowed stock blocks up to 6 litres (366 CI) between 1930 and 1936, a stock block never finished any higher than third, with Cliff Bergere in 1932. Smaller engines with a racing pedigree (DOHC technology) weren't going to be beaten by the stockers.

In 1932 and 1933, Studebaker entered a fleet of Rigling chassis powered by straight-eight Studebaker Premier 8 engines. This car, driven by Cliff Bergere in 1932, came home third, the best-ever result for a stock block engine for a long time to come. (photo HG)

Studebaker also won a pole position, courtesy of Russ Snowberger in 1931, so one could say that Studebaker was pretty much the factory scoring the best results. But they were by no means the only company represented at the Speedway.

There have been a few attempts with Chrysler engines in Indycars. This car, however, is the only car with Chrysler power to have ever raced at Indianapolis. It ran the 1932 and 1933 races. When its active career was over, it was rebuilt into a Grand Tourer, street legal and all. Stock block technology returning to its roots… I located this car in 1997 in the Nationaal Automobiel Museum at Raamsdonksveer, the Netherlands. Some time after that, however, it was sold off and disappeared out of sight. (photo HG)

Other examples of the junk formula racers were the Hudsons. This one, owned by the Nationaal Automobiel Museum at Raamsdonksveer is supposedly Chet Miller’s 1932 car. (photo HG)

The longest lasting attempt was the 1935 Ford project. Edsel Ford and Preston Tucker ordered Harry Miller to built ten front-wheel driven chassis powered by Ford V8 engines. Only four cars were finished in time to qualify for the race and all retired with frozen steering gears. In later years, some of the Miller chassis were fitted with various other engines and some of them gained creditable results, supporting the knowledge that the chassis itself was a fine piece of equipment. The original Ford V8s had some 160 to 170hp. Team owner Lew Welch fitted one with an Offy and gained a third and a sixth place with it. In 1941 Welch tortured the poor chassis when he had the brand new supercharged Winfield V8 built into it. That engine is better known as the Novi. The extra 80 kilos of weight and 450hp made the fine-handling Miller turn into an evil-handling monster. With power reduced to some 250 to 275hp the car performed acceptable enough for driver Ralph Hepburn to race it and even finish fourth with it.

The 1935 Miller-Ford owned by the IMS Museum. Several of these cars are still in existence today. (photo HG)

Another of the 1935 Miller-Ford cars. This one was photographed in 1999 when it was privately owned and part of the Racing Car Museum's collection in Bedford, IN. (photo HG)

Some of the very exclusive Duesenberg production engines were also used in the junk formula years. Because of their overhead camshafts they offered more potential than a number of other pushrod stock blocks of contemporary size. Here is one such Duesy engine. (photo HG)

Although the stock block never won the big prizes, particularly in the early years of the junk formula (when it had yet to be proven that engines with a racing pedigree still had an advantage) they helped to keep Indianapolis and racing alive and got it through the difficult first years of the Great Depression.

In the part about equivalency formulas I mentioned the early-fifties attempt to give the stockers a full litre of additional capacity and how that rule was killed off instantly once such an attempt appeared to stand a good chance against the Offies. By that time the most serious option coming from Detroit, with the highest degree of sophistication, was a V8 with a single camshaft operating two valves through rocker arms and pushrods. Reading the list of cars that failed to make the race as printed in Jack Fox's 'bible of the Indianapolis 500' you find several cars fitted with engines that must have had a stock-block heritage. Names like Chevy, Cadillac, Chrysler and Studebaker appear in the lists covering the first half of the fifties. In the second half of the fifties I found a deSoto and a Jaguar.

Front-engined stock block-powered roadsters remained a rarity. Chuck Chenowth built and entered a smallblock Chevy-powered roadster for the 1960 race but the car arrived late and never made it onto the track. One year later Mike Magill drove this handsome-looking sleek creation but persistent oil leaks prevented any serious runnings and during its second qualifying attempt the Chevy blew. Not entered in 1962, the engine was more durable in 1963 but neither Bud Tinglestadt nor Mike McGreevy nor Colby Scroggin was able to find any speed in the car.

Mickey Thompson brought stock blocks prepared for racing to Indianapolis in 1962 when he fitted his rear-engined cars with Buick V8s. Dan Gurney managed to qualify one of the cars. One year later, Thompson came with yet more cars including the tiny wheeled 'Rollerskates' while switching to Chevrolet engines. The Kimberley Specials - rear-engined as well - were Buick-powered but failed to qualify.

Ford built aluminium versions of the Fairlane stock block in 1963 for use in the Lotus and was rewarded with Jim Clark’s fine second place. Cliff Bergere’s record finish for a stock-block engine - third in 1932 - was bettered at last.

Chuck Daigh’s rear-engined Thompson-Buick. He failed to qualify but Dan Gurney made the race in another Thompson entry. (copyright First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

Mickey Thompson’s new cars for 1963 were nicknamed 'rollerskates' and had Chevy engines. This is the titanium chassis driven by Masten Gregory who failed to qualify the car for the race. (copyright First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

The Lotus-Ford prototype, 'the Mule', in the Spring test session. The engine lacks the tuned exhausts that were used later on. (copyright First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

I'm not allowed to tell where and when I saw this engine but this is one of the nine original 1963 aluminum Ford Fairlanes that were used for the 1963 Lotus-Ford project. (photo HG)

The Fairlane engine was then developed into a DOHC Quadcam version but that is a different story. But it deserves mention here that the DOHC Ford Quadcam in all its varieties was derived from a stock-block design.

One of the most bizarre cars ever at the Speedway was the 1966 Valvoline Special #79 entered by Albert Stein. It was a conventional tub frame but carried two normally aspirated 2-litre Porsche flat-6 production engines of 911 background - one in the front, one behind the driver, each driving an axle. Driver Bill Cheesbourg failed to qualify the ungainly creation.

In the late sixties the rules again allowed for additional stock-block capacity and so Dan Gurney finished second twice in his Weslake-Ford in 1968 and ‘69. However, this project doesn’t entirely qualify as stock since Gurney used specially designed cylinder heads designed by Harry Weslake.

By that time (1968) the engines to have were the turbocharged 2.8-litre DOHC engines that from 1969 on were reduced to 2.65 litres. The development level on these engines reached such levels that normally aspirated engines, be it DOHC or with pushrod technology, became a waste of effort.

When the turbine engines were banned the STP team reverted to an incredible variety of cars and engines, including Plymouth V8 stock blocks of 5.2 litres (318CI). None of these managed to qualify at Indianapolis. That year, Mario Andretti won with the turbocharged Hawk-Ford STP entry. The car above is a 1969 Gerhardt-Plymouth. Art Pollard drove it in the 200-miles race on the high-banked oval of Dover on August 24, 1969, an event counting towards the USAC National Championship. Stockblocks rarely won in paved USAC races but this is one of the few to ever achieve the feat. (photo HG)

There were no attempts with normally aspirated stock blocks during the early seventies. The rugged turbocharged Offies were capable of a fairly reliable four-figure power output so no way that any sensibly sized atmo engine still able to fit into an open-wheeled single seater could ever achieve such power levels. During the mid-seventies the boost controlled Offy, Ford/Foyt V8 and Cosworth DFX were still no match for atmo stock blocks.

But from 1979 on, the normally aspirated stock block became a viable option again This was enhanced by USAC who had already increased the maximum permitted capacity of normally aspirated stock blocks up from 5.2 to 5.8 litres. This, in addition to even more restricted boost levels for the turbocharged purebred racing engines, brought their power outputs back to levels that were attainable for stock blocks as well. By the way, the 5.8-litre capacity was also used in NASCAR and so USAC hoped that some of the knowledge obtained in NASCAR could inspire the USAC scene. And of course, the technology was readily available too…

Phil Threshie was the first driver since Dan Gurney who qualified a normally aspirated stock block. His Kingfish-Chevy was the only non-turbocharged car in the field in 1979. Starting 29th he was classified 17th and running, credited with 172 laps at the finish.

But once again it was Dan Gurney who was the big promoter of the normally aspirated stock block, using the Chevy in his new Eagle. This Eagle was of a radical new design, using some kind of ground effect and the team had difficulties in making the technology work. Mike Mosley eventually qualified the car for the race but made his first pit stop after three laps, the second after five laps and then retired with engine problems.

The second Chevy-powered car that qualified was the unsung hero and a crowd favourite. Upcoming driver Roger Rager had installed a Chevy in a Wildcat chassis and proclaimed that the block had originally been used in a schoolbus! Now how much of this story is actually true remains a question. Rager crashed after 55 laps.

A third and final Chevy-powered car that made the cut also had quite a story to tell. Originally, it had been a McLaren M16C built in 1973. It had been with the Dayton-Walther team but was bought by driver Jerry Karl for 1979. That year he built a wing car around the monocoque and fitted it with a Chevy V8. He lost the clutch after 64 laps.

A highlight at the Speedway in this new burst of normally aspirated stock blocks was the second place on the grid for Mike Mosley in 1981 with his factory Eagle but sadly, he became the first retirement of the race with engine failure. A fortnight later at Milwaukee, when the car was fitted with the engine scheduled for Indianapolis two weeks before, Mosley won the race despite starting from last place! This was one of the very few defeats the Cosworth DFX suffered in the years from 1979 to Long Beach 1987, when the Ilmor-Chevy won its first race.

May 2011: Once upon a long time ago this car… (photo HG)

…looked like this… (photo HG)

An example of the early eighties Eagle-Chevrolet of which several were built and ran in private hands. The car (here is one in the shape introduced in 1981) designed by John Ward appears to lack any sidepods, so it didn't have ground effects. It did however use a different way of creating a vacuum beneath the car which was initially very efficient too, but later on it appeared to be lacking enough development potential. This type of car can be credited for reviving the interest in normally aspirated stock blocks at Indy from 1980 on. This type of Eagle could be fitted with turbocharged Chevies and Cosworths as well but the majority of them used 5.8 litre (355 CI) Chevies. (photo HG)

Stock? Now that depends. A number of parts in these engines were aluminium versions of the genuine production parts, often manufactured by the world of after-market suppliers. But since their design was similar to the standard part USAC considered it stock. USAC had done something similar a few years before with an engine we will see later on.

USAC had also announced plans to ban the quadcam racing engines and prescribe stock blocks from 1982 on! However, during 1981 this plan was put on hold, and quadcams were here to stay.

Several Eagle-Chevies ended up in private hands but apart from Michael Chandler’s 9th place in 1982 none of these scored any decent results at Indianapolis. Gurney tried turbocharged Chevy V8s but these brought him nothing but engine failures before he switched to atmospheric Pontiac V8s in 1984. Eventually he went back to Cosworths too.

The stock blocks gained some popularity in CART's road-racing events during the early eighties because of their higher flexibility, instant reaction and torque. Truesports, at that time an upcoming team with the promising Bobby Rahal, used a March-Chevrolet in some of the 1983 CART road races and could have won at Mid-Ohio. Eventually he finished third.

The final attempts with normally aspirated stock blocks at Indianapolis took place in 1987 when Sammy Swindell qualified a March-Pontiac 86C but got bumped. In 1988 Dale Coyne entered a March 86C with a 6.5-litre (390CI) Chevy stock block. Dale was unable to use a more modern chassis because none of these could accommodate such a big engine and all the auxiliary equipment it required. USAC wanted to promote the big blocks at a time when the chassis builders built ever smaller cars for ever smaller frontal areas.

The Coyne entry kept blowing and leaking oil all the time, and it was nearly impossible to make the Chevy run at any speeds above 140mph. And that, for the time being, was the swansong for normally aspirated stock blocks at Indianapolis.

I never got the opportunity to take a full picture of the Coyne entry with its engine in the car, but this is one of the blocks Dale Coyne used in his 1988 entry. (photo HG)

One could say that there was something of a revival for normally aspirated production-based engines from 1997 on. But that is beyond the scope of this work and hence I won’t deal with those.

Rushing through seven decades I ignored a number of projects and an entire category of stock block engines that need more attention. So now let's focus on these in more detail.

The earliest blown and turbocharged projects

In this section we will take a look at the earliest attempts with blown stock blocks before the concept really caught on.

Of more interest for this study on the `94 PC23-500I is the introduction of the turbocharger at Indianapolis. But before its arrival the mechanically driven supercharger had gained quite a reputation and written a lot of history at the Speedway.

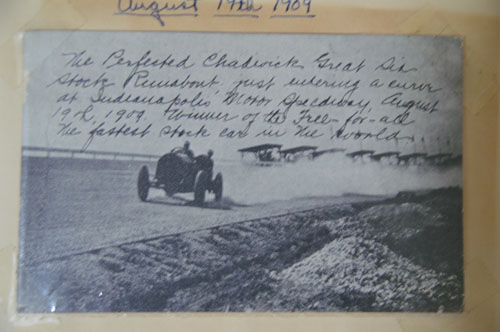

The first confirmed supercharged stock block ever at Indy was entered even before the 500 was held for the first time! Len Zengel drove one of the blown Chadwick cars in several of the events already held at the Speedway in 1909. The Chadwick was a hopped-up version of the Chadwick passenger car which could be supplied with a supercharged engine.

Len Zengel was the winner of a 10-mile race on August 19th 1909, driving this Chadwick 'Great Six' Runabout, the first-ever victory at IMS for a car fitted with a blower. These pictures were found in a scrapbook created by an unknown racefan. The origins of the pictures are unknown but they were printed as postcards. The images as provided here are from the cards as stored in that particular scrapbook. (photos HG)

Apart from the Chadwick, the first supercharged cars at Indianapolis were the 1923 Mercedes cars, followed one year later by the Duesenberg followed and in 1925 by the Miller. As for the question of what was the first blown genuine stock block, this is a bit obscure.

The Jack Fox 'Illustrated History' bible is listing a supercharged Fronty Ford-powered entry in the 1926 race. The Fronty Fords were based on the cylinder block of the venerable Ford T engine but fitted with a Frontenac-designed and built DOHC cylinder head - so not really genuinely stock but about the closest you can get. I don’t think it qualifies as a stock block but deserves to be mentioned in the 'close but no cigar' contest…

Thus, to the best of my knowledge, a genuine supercharged stock block was never entered let alone raced in the '500'. I do have a candidate however, which I will discuss later on.

But there is one more project that needs to be mentioned in this overview.

The Howard Keck stable who fielded Bill Vukovich between 1952 and 1954 needed a new car for 1955 when its old KK500 Roadster, the nearly invincible Fuel Injection Special, was past its prime and needed replacing. Frank Coon and Jim Travers, Keck’s mechanics, designed an advanced full-bodywork streamliner expected to be heavier than a regular roadster. So a more powerful engine was needed. Keck almost pulled off a coup to obtain a Novi V8 from Lew Welch but Welch backtracked on the plan. Coon and Travers then commissioned Leo Goosen to design them a new blown V8. Goosen did design a DOHC V8 but the cylinder block he used was that of a stock De Soto V8. As for the blower, it appears the engine could have used either a Roots or centrifugal supercharger, a concept more familiar to Indianapolis. Regrettably, this engine never went beyond Goosen’s drawing board. Otherwise it could have been the closest thing to a mechanically blown stock block to ever appear at the Speedway to contest the '500'. But maybe, just maybe, by virtue of some creative thought, one could argue that a mechanically blown stock block had been at the track already, even before Keck’s Streamliner with a De Soto-based supercharged V8 was canned.

In the first version of this chapter, published in December 2009, my research for the first production-based engine with mechanical supercharger used in an Indycar had led me to the two 1934 Cummins Diesel entries of that year. I included the pictures of the two stroke diesel #5 and four stroke diesel #6 that I had taken over the years. Early July 2012 I was contacted by Dan Marelli from Tallahassee, FL, who pointed out to me that the #5 as I had photographed wasn't the original car as raced at Indy anymore. After the race the chassis had been lengthened and fitted with a longer 6-cylinder four-stroke engine and the car was used to attempt land speed records at Daytona Beach. Searching into this matter I concluded that, indeed, the car as I saw it was different from how it had raced at Indy 1934. I did more research on the Cummins Indy efforts and found out that the two engines used in 1934 were not production units yet, but prototype blocks in order to investigate if the two-stroke design had an advantage over the four-stroke yes or no. In other words: the two 1934 Cummins cars simply can't be the first Indycars with supercharged engines with production heritage anymore. That distinction goes to another car.

Searching through the 'Fox Bible' the only other listed supercharged car that ran during the years of the junk formula was a two-stroke sixteen-cylinder built by Leon Duray. Now, supercharging was only permitted on two-stroke engines so that may explain that. Supercharging four-stroke engines was permitted again from 1937 on. On the other hand, the Fox bible failed to list the 1934 Cummins Diesels as being supercharged. So one or more production-based engines fitted with a centrifugal or Roots blower may have been overlooked in the book. Specially in the last few years before the war and right after there might have been an overlooked obscurity that failed to qualify.

Assuming that the Fox bible is complete and accurate, it still does list a candidate for what by now is the most likely first production-based block fitted with a mechanical blower that qualified for the race. As said, supercharging four-strokes was permitted again from 1937 on. The Fox bible lists a supercharged Bugatti (#49) driven by Luther Johnson in 1936 that failed to qualify and this entry causes some confusion. But the starting list of 1937 lists an entry that most likely is the first mechanically blown stock block in the “500”. Russell Snowberger had built his own chassis and fitted it with a 282 CI eight-cylinder Packard engine which is listed as supercharged. Snowberger qualified 30th and finished 27th after his clutch failed after 66 laps.

A definitive list of mechanically blown production-based engines at Indy remains difficult to find. There may have been a few more at the track in the years from 1937 on but since the engine formula changed in 1938 to the 3-litre supercharged or 4.5-litre atmo limits the bigger stock blocks disappeared from the scene. And against four-valve race-bread engines of the same capacity pushrod engines stood little chance.

Anyway, mechanically blown production-based engines remained rarities. For about the only one of which I am sure it existed and made the race we have to go to 1950. Cummins again tried their luck in the Indy 500 in 1950 after ordering a lengthened version of the Kurtis Kraft KK3000 in which a Roots-blown six-cylinder diesel engine was fitted. This six was described as a much lightened version from a production engine. So perhaps it wasn’t entirely stock anymore but this was as close as you can get. When we remember that back in the late seventies and early eighties USAC allowed a similar approach with Chevy pushrod engines and still rated the engines as 'stock' I think it is fair to accept a similar approach some 30 years earlier with this Cummins Diesel as well.

The actual car was nicknamed 'Green Hornet' after its colour. It was driven by Jimmy Jackson and the slowest qualifier in the field that year. Ironically, it pretty much owed its starting place to the fate of two other supercharged cars failing to qualify. The Novis with their supercharged 3-litre V8s were the most powerful cars entered and should normally have made the field with ease. But due to all kind of troubles around and within the team both cars failed to qualify, enabling the Cummins to make the field, be it with the slowest qualifying speed. In the race Jackson had to retire after 52 laps with supercharger failure.

The 6.6-litre Cummins Diesel engine in the 1950 factory entry, nicknamed 'the Green Hornet'. (photo HG)

Even more memorable is the 1952 Cummins car that Freddie Agabashian qualified on pole. This revolutionary car, built in close cooperation with chassis builder Frank Kurtis, was a pioneer in both chassis and engine technology, and one of the very first, if not the first racing car competing in a major event with a turbocharged engine, albeit a diesel - so be it. The engine was a modified and lightened 6-cylinder 6.6 litre (401 CI) derived from a production unit.

The legendary 1952 Cummins Turbo Diesel was powered by an lightened, aluminium version of a production truck engine - by all means one of the most revolutionary cars ever in Indianapolis history and motor racing history in general. Driver Freddie Agabashian was involved in the project from the start.

(photo courtesy of IMS Photos, used with permission)

Those four Cummins cars can be earmarked as the first three (mechanically) supercharged - and as far as I could figure out the only ones as well! - and turbocharged stock blocks at Indianapolis. Although I'm aware of the fact a number of purists feel disgusted about racing diesel engines I think the Cummins engines at least may be mentioned and nominated for these honours.

Even when people say that the 1952 engine wasn’t stock but specially made with lightweight parts and so on: well, those atmo Chevy engines of the early eighties I mentioned above contained a lot of parts that weren't off-the-shelf but specially made for the after-market hotrod world, so pretty much the same approach as with the 1952 Diesel. But in the Chevy's case these aluminium after-market parts were still rated 'stock' by USAC. So if those Chevies were 'stock' the same can be said about the 1952 Turbo Diesel.

Diesels were put out of business after their 1952 success, so by now it's time to turn our attention to regular gasoline and methanol-fuelled blown Otto-principle four-stroke engines.

No blown stock block in the true sense of the word anymore for a while but the Ford Quadcam Turbo, introduced in 1968, will be mentioned here as being derived from what was once a stock block design. But I won’t nominate it for being the first-ever turbocharged stock block at Indianapolis.

If we ignore the 1952 Diesel the first turbocharged stock block at Indianapolis was a six-in-line AMC Rambler engine, entered by Barney Navarro in the late sixties and early seventies. The car never made the race but maybe that had more to do with the chassis in which it was installed: one of the very first rear-engined Watsons of the mid sixties (Rodger Ward's 1964 mount in which he finished second). According to rumours, Navarro eventually had two turbos on the engine but I haven't found any evidence for that.

The next turbocharged stock block attempt is certainly worth mentioning because this was definitely the first Indycar ever with two turbochargers that actually qualified for the race. In 1972 Smokey Yunick fitted a Chevrolet V8 with two turbochargers, installed it in an Eagle and the car driven by Jerry Karl qualified for the 1973 race. It was listed as being flagged off after 22 laps...

Although the actual Eagle chassis that used the Yunick twin-turbo Chevy is in the collection of the IMS Museum, it is difficult to find pictures of the car showing off some of the construction details of its engine. Here are two of such pictures which at least show something, taken in 1973. (photo copyright Jim Edwards Collection, provided by Bill Ashby, used with permission)

Nevertheless, this particular attempt is unique in Indianapolis history since as far as I can figure out, apart from it being the first-ever turbocharged stock block in the race, this is the first turbocharged car ever at Indianapolis with more than one turbo. Right up until 2012 it remained the only car with that feature. A new engine formula was introduced in 2012 that prescribed turbocharged V6 engines with either one or two turbochargers. Chevrolet and Lotus chose the twin-turbo option so Smokey’s 1973 engine finally lost its distinction as the only twin-turbocharged engine ever to race at the Speedway. The car was entered again in both 1974 and 1975, Sam Sessions was left in the qualifying line in 1974 thus missed the race. But Jerry Karl was back in the car in 1975 and finished a very creditable 13th. The 1973 effort in particular deserves acclaim. By design alone, the Chevy wasn’t built as a high-power producing engine but Smokey managed to have it generate enough power to take on the high-boost Offies that were capable of producing 1000 and more hp in qualifying. Making the field was an achievement in itself. I found some details about the 1975 engine: it was based on the 283 block (4.7 litre) and for 1975 Smokey claimed 850hp.

From 1976 to 1979 there were attempts with a turbocharged AMC V8, driven by Jerry Grant (’76), Jim McElreath (‘77), Roger McCluskey (’78) and Jerry Sneva (’79). The engine eventually provided decent amounts of power, and in 1979 the cylinder block became of aluminium too, reducing weight even more. More parts were made out of aluminium but these were identical in shape and design to the stock version, so declared 'stock' by USAC. Race Day results were not that impressive, however. The major problem with the entire project was that the used cylinder blocks castings simply were not tough enough to cope with that much horsepower. Nevertheless, the AMC efforts gave USAC visions of cheap, US-built engines competing at the Speedway against purebred racing engines.

Not a purebred stock block (now why do I consider that a contradiction?) project was the Crower Flat Eight introduced in 1977. Built by Bob Bubenik and Bruce Crower, this turbocharged engine used a purpose-design crankcase. The two cylinder heads were angled at 180 degrees, making it a flat engine, pretty much like the Ferrari and Alfa Romeo flat-12 engines used in Formula One, or the Porsche boxer engines. The two cylinder heads, however, were taken from the Chevy Cosworth Vega. But these heads were DOHC 16 valve heads, based on the Cosworth DFX heads, so definitely a racing pedigree, yet still with a stock background because these heads were used in a production car offered for sale. The car fitted with this engine never made the race but Bubenik and Crower were awarded the 11th annual SAE Indianapolis Race Car Design Award. The project was hit by the fact that the cylinder heads weren't designed for a vertically oriented engine, and so oil scavenging problems resulted in overheating and lubrication troubles.

In 1979 USAC relaxed the stock block rules for normally aspirated engines. But inspired by the AMC efforts they did the same for the turbocharged ones. Their capacity was kept at 3.43 liters but they were given an extra 8 inch of turbo boost. The Quadcam V8s were restricted to 50 inch, the stock blocks were permitted 58 inch. Still the AMC mentioned above (this time with an aluminium version of the cylinder block) was the only turbocharged stock block in the starting field that year. Ironically enough, although it inspired the rules that should have made the turbocharged stock blocks more competitive the AMC never qualified for another '500' since.

It is 1980 now, and we come to what is likely one of the darkest episodes in USAC rulemaking. Before, there were other occasions in which USAC killed off a promising option in order to protect the traditional team owners' investments - think of the additional litre of capacity given to stock blocks at first but taken away once such an engine produced good test results. But the matter I bring up for discussion here was aimed against a single constructor needing to be kept out of competition.

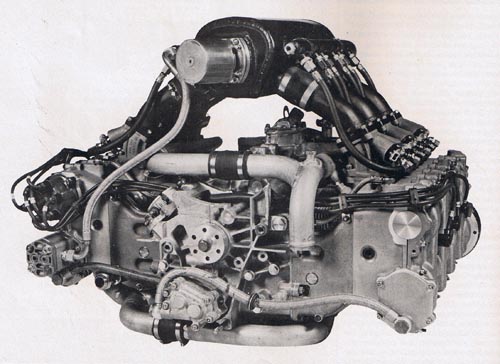

In its quest to keep the old four-cylinder Offenhauser engines competitive against the Cosworth DFX, USAC had introduced a variation of boost levels depending on the amount of cylinders. The fourbangers were given a boost level slightly above 1 bar (60 inch) while the V8s ran on 0.6 bar of boost (48 inch). There were no six cylinders in use yet but that was about to change: enter Porsche!

Porsche decided on an attempt to win at Indy using an engine derived from their venerable six-cylinder boxer engine. Originally derived from the engines used in 911 production cars, the racing versions of their turbocharged flat-6 had proved themselves capable of producing serious amounts of power in both GTs and sportscars. For the time being the Porsche was developed to run on a boost level in between that for the V8s and the fours, 0.8 bar (54 inch) to be exactly, but USAC was yet to decide if this boost value was final.

By that time, single-seater racing in the USA was in turmoil because of the row between USAC and the newly founded CART organisation. They disagreed on many things except one: both feared Porsche for their reputation to eventually dominate any series they entered - sportscars and Can-Am with the 917, GT racing with the 934, silhouette Group 5 and IMSA GT with the 935, and sportscars again with the 936. On top of that, a factory-supported effort against the privateer teams racing in both USAC and CART made both parties feel uneasy. The solution to keeping Porsche out of the '500' was made easier by one big weak point in the Porsche project: they were the only constructor using a DOHC six-cylinder engine.

USAC sent two inspectors to have a look at the Porsche engine in order to make a final decision on its mandatory boost level. The result was that USAC informed Porsche that according to them the current engine left lots of room for major improvements. So by introducing the rule that every engine with more than four cylinders - which effectively had been V8s up until that point - had to run on the same amount of boost, USAC victimized only one single engine: the Porsche flat-6!

The Porsche flat-6 Typ 935/72.

The Porsche flat-6 wasn’t a bespoke racing engine, so it wasn't capable of keeping up with bespoke racing V8s, let alone what was at the time the ultimate racing V8 ever built: the Cosworth. There wasn't enough time to improve the flat-6 so that was the end of the Porsche project. Although it appears that communications between Porsche and USAC were not always as they should I still think this was a case of USAC abusing their equivalency politics in order to prevent the participation by a competitor that wasn’t welcome.

Now readers might feel that this project doesn’t belong here since the Indy Porsche flat-6 had little left to do with the original production stock block. Well, if that's the case I must withdraw the supercharged DeSoto-based Keck V8 and the Turbo Ford/Foyt as well.

Having dealt with a 1980 project that didn’t make it, let’s now look at the stock block projects that did happen in 1980. Apart from two normally aspirated Chevy V8s, another type of Chevrolet stock block was represented in the 1980 starting field. Lindsey Hopkins’s team had one of its cars fielded with a turbocharged V6 Chevy. Hurley Haywood used this engine fitted in a Lightning chassis and was classified 18th when the turbocharger broke after 127 laps. In fact, he was the highest finisher of the three stock blocks. This V6 was a rather new generation of engine, derived from the V8 Chevy. Chevrolet was partly involved in order to promote the new concept while well-known engine builder Ryan Falconer and his company were involved in the preparation of the USAC racing version.

For 1980 the boost for Quadcam engines was reduced by 2 inches while the stock blocks retained their 58 inch, increasing the boost differences between the two types of engines. Apart from the atmo Chevies, a turbocharged Chevy V8 qualified for the 1981 race but didn’t impress in the race. There were no V6 Chevies in the race. Despite the relatively unimpressive results of the turbo Chevy V8, Dan Gurney switched over to them in 1982. But the engine was catastrophically unreliable, driver Mike Mosley (in the middle of the front row the year before with an atmo Chevy) failed to qualify and it almost broke Gurney’s team. A single turbo Chevy V8 made it into the field at Indy, failing to impress and the attention then shifted to V6 stock block engines of the turbocharged variety.

Two turbocharged Chevy V6 entries tried in vain to qualify for the 1982 race. Five turbo Chevy V6-powered cars were entered in 1983 but none of them made it into the starting field. One year later the era of the turbocharged stock block entered a new phase. Remarkably enough, the Chevy V6 was hardly involved in this rise to power for the stock block but another member of the GM family would take care of it.

From 1984 on, the turbocharged stock block became a viable option, taken more seriously than ever before.

The first years of the Buick era (and about a 'blowtorch')

From here we take a look at the attempts in the decade preceding the Penske-Mercedes 500I, a decade that would be decisive for the Ilmor 265E/Mercedes Benz 500I to become a reality.

Chevrolet engines had been the most popular stock engines used at Indy but their success in 1983 had been far and in between. If it came to the turbocharged variety, the V6 appeared to have the most potential. But after 1983 Chevrolet pretty much disappeared from the scene. And another partner within General Motors took over the relay baton. The Buick V6 made its debut in 1984 but got most of its media coverage because one of the two Buick-powered cars in the field was involved in a horrifying crash that fortunately wasn’t fatal to driver Patrick Bedard.

Indianapolis was rarely covered by the Dutch media before Arie Luyendijk went over to race there. If it was, it almost always centered around accidents like those of Ongais and Smiley. This was another picture too good to be ignored: Patrick Bedard’s 1984 accident in which he wrote off his March-Buick 84C. (clipping from Dutch newspaper Algemeen Dagblad)

Two cars powered by such hopped-up Buicks took the first two starting positions in 1985. Pancho Carter won the pole with new track records for four laps but he was out of the race after 6 laps and finished dead last. This pole for Carter was the first for a stock block since 1931.

Scott Brayton was second fastest and had set the new lap record. Coming out of the final turn he felt his gearbox seize up and thus coasted to the finish. It cost him the four-lap record and pole. In the race he was out after 19 laps as the fourth retirement. The only other stock block in that race - we’ll talk about that one later on - was the second retirement of the race.

The car driven by Scott Brayton in 1985, a March-Buick 85C. (photo HG)

March boss Robin Herd was involved with a factory-supported effort that fitted a March 86C with a Buick V6. The car showed tremendous pace during test sessions in April ’86 but in May the results were almost disappointing.

The general consensus on the Buicks was that they were more powerful and had more torque as well. But due to their smaller rev range the cars in which they were used had more difficulty setting up their gear ratios. At the track the engines were less flexible too because of their larger pistons and indirect valve activation. Most worrying of all, their reliability on Race Day was appalling.

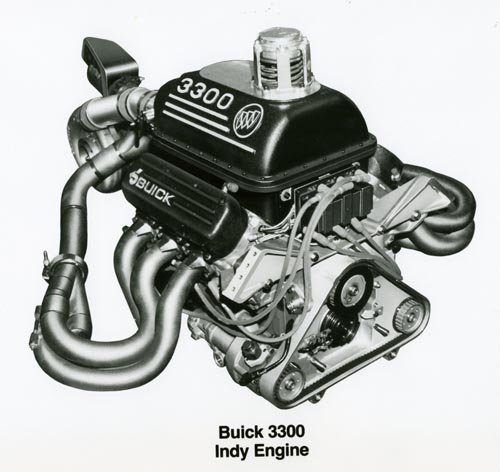

The official Buick PR shot of their 1988 engine, as found in the Buick press kit.

It was in 1988 that a Buick-powered car finally became a genuine dark horse and went on to make a big impression during the race. Jim Crawford took care of that by finishing sixth (after qualifying 18th, although his speed ranked much higher) credited with 198 laps after a strong race in which he appeared to be one of few who could do anything against the all dominant Penske-Ilmors.

I don't have any decent pictures of Jim Crawford’s 1988 car but this picture may prove even more how extraordinary a man he was. He had crashed heavily in 1987 and injured his legs quite severely. Walking was still difficult for Jim in 1988, hence the cane. But once assigned to a Johnny Rutherford back-up car his walking difficulties didn’t slow him down one bit. He outshone team leader Rutherford handsomely and rapidly became a crowd favourite that year and remained so thereafter. From 1988 until 1992 Jim was one of the outstanding, most spectacular Buick-powered drivers. '500' winners Jim Clark and Dario Franchitti may be the most successful Flying Scots at the Speedway, Jim was likely the bravest Scot ever to venture there. This picture is a tribute to a wonderful, brave, crowd-pleasing driver, and an asset to the Buick project, who deserved much better. (photo HG)

Although the Buick was the most prominent stock block in action, one other engine deserves attention.

As already stated, Chevrolet was no longer active with its turbocharged V6 since 1984 but one man kept faith and carried on developing it. But if the Buicks were infamously known for their unreliability, even worse reliability was endured (more correctly, suffered…) by AJ Foyt’s turbo Chevy V6 stock block that appeared in 1984 for the first time, built into a March 84C and failing to qualify. In 1985 it went into a 85C and George Snider made the field with it, only to retire after 13 laps. Had Pancho Carter not retired seven laps earlier, Snider would have scored the first 33rd and last place for this engine. The engine was promoted into an 86C chassis one year later and that was its final destination. The engine had lots of power and once fitted in the 86C chassis had enough speed to make the field fairly easily. But its reliability…

In some of the years that followed, the engine miraculously survived a qualifying attempt only to break within the first three laps of the race, no matter who drove it.

AJ himself wisely stayed away from the contraption, but (as it has been described) he tested his friendship with buddy George Snider about every year by giving him his annual chance to qualify for yet another inevitable miserable Race Day performance. It has been suggested that Snider’s retirement from racing was partly to do with AJ only assigning him the Chevy but that was denied by George himself on live TV.

In three starts, the engine did 13, 0 and 2 laps respectively, and was classified 32nd, 33rd and 30th. Had it not been for Stan Fox avoiding the first-lap crash in 1988 that eliminated three cars, that highest finishing result of 30th should have been another 33rd.

In order to prove the fact that the engine was the unreliable part of the car George Snider qualified a Foyt-owned Cosworth-powered 86C in 1986. The car was wrecked in a curious crash that took place on Carb Day. It was unrepairable but the rules permitted Snider to start an identical back-up car. Foyt Racing hurridly converted the 86C-Chevy (which had failed to qualify) to Cosworth power and George made the start. He retired with engine troubles after 110 laps and was classified 26th. This was to remain the highlight in this particular 86C monocoque's career.

'The Blowtorch'. AJ Foyt’s March 86C-Chevy V6 Turbo, here seen in 1988, driven by Stan Fox. (photo HG)

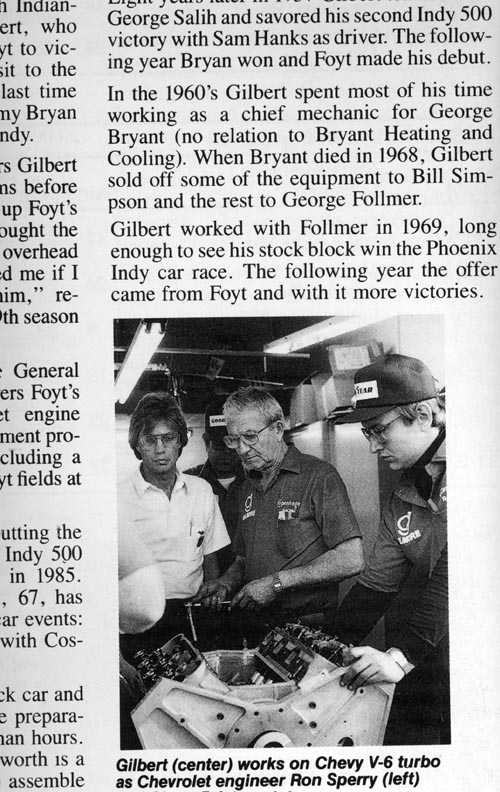

Needless to say it was a bit strange to see two different GM companies represented at Indy with a pushrod turbo V6. But neither AJ’s Chevy nor the Buick were factory-supported projects. And the V6s differed from each other in a number of details related to materials used, the crankshaft design and the location of the valves in the cylinder head. The Chevy V6 was derived from the Chevrolet big-block V8 and incorporated valve train characteristics as found in Chevy V8 truck engines. Head and block were made from aluminium. The valve train was offset, unlike on the Buick which had in-line valves. The offset design offered the potential of employing larger valves, an asset for the two-valve engine. The crankshaft had solid pin connecting rod journals whereas the Buick had offset journals in the same plane. The benefit of the solid pin construction was its enhanced strength but it resulted in an uneven firing order which tended to set up a harmonic vibration condition through given engine speed ranges. Work on the engine was done by AJ’s long-time engine man, Howard Gilbert.

I found statements to the effect of Foyt continuing to enter the V6 in order to attract Chevrolet's attention and prove the engine's potential. I don’t know if this is true. Between 1980 and 1983 the Chevy V6 program had yielded little, despite the involvement of a big name like Ryan Falconer.

Of course, Chevrolet was involved in CART/Indycar with the Ilmor Chevy/A since 1986. Foyt’s attempts to show the potential of the V6 might have made some sense in ’86 and ’87 when the Chevy/A was still far from reliable. But a DNQ and 33rd (retired before the actual race started!) in these two years were, if anything, even more embarrassing than what the Chevy/A-powered drivers managed to achieve in those years. After the Chevy/A finally came good in 1988 and when Foyt’s 'Blowtorch' was out of the race after 1% of the scheduled distance, the V6's fate was pretty much sealed when it came to the chance of securing Chevrolet support.

The last time Foyt entered the engine was in 1990, still in a March 86C. According to the Day-by-Day records of that year, it was AJ himself who took the car out for practice on May 11, driving 19 laps. The fastest lap he achieved was a 212+. To put this into perspective: AJ and his four-year old March car weren't that much slower than the fastest laps achieved by either Roberto Guererro and Al Unser Sr in the Alfa Romeo-powered 1990 March 90CAs!

Mercifully, Foyt gave up on entering the 'Blowtorch' after 1991. Curiously enough, he did enter a Buick-powered car to be driven by Bernard Jourdain that year!

So how to rate this project? First of all, I am doing this with the benefit of hindsight. For starters, the project had the misfortune of Chevrolet becoming involved with the Ilmor 265A. Even Chevrolet had no reason to commit themselves to developing two entirely different engines, one of them suitable for use only at Indianapolis. And like Buick, Chevrolet belonged to General Motors. When did GM ever see the need to have two of their companies take each other on in Indycars that had slightly different engines yet built according to the same rules?

But, again with hindsight, the mid-eighties were also the years when Indycar engines outgrew the capabilities of its more traditional engine suppliers. They became more high-tech than ever before. And despite AJ’s background as an engine builder (remember the Ford/Foyt days) it appears as if developing a decent turbocharged stock block had by now become a bit too much for AJ’s facilities. This wasn't something AJ Foyt could be blamed for, the times were simply changing. It took more effort to keep up with competing engineering companies and it seems AJ and his men and facilities couldn't keep up with the trend. The Buick finally came about good after a lot of manpower and several companies putting their efforts into it. AJ’s Chevy lacked all of that.

Besides that, looking back on that period of time in AJ’s career, his efforts at Indianapolis appear not to have been entirely focused. Several young and upcoming drivers were all too happy with AJ being distracted into helping them out by getting them a drive to have them make the field as well. In a time it became increasingly more difficult for young upcoming American drivers to get a drive at Indianapolis, AJ was a firm supporter of American racing talent and helped out quite a number of young drivers.

But how did running all those cars over the years affect AJ’s focus on his own car and his own driving? How much did he compromise his own results? All of what he did still added to his legendary status at Indy but was it beneficial to his race results?

And how serious did he take the project? How much faith did he have in the engine? AJ never gave the impression he was going to race the engine himself. So if he was so convinced about the engine why didn't he drive it himself and participate actively in its on-track development?

I obtained three different AJ Foyt media guides, those from 1988 to 1990. The 1988 guide briefly mentions the engine on the page devoted to engine man Howard Gilbert. The 1989 and 1990 guides don’t even mention it, nor can any construction details be found in either booklet.

AJ's (or Howard Gilbert's?) toy: the Chevy V6 stockblock built into its March 86C, seen in 1988. As can be seen, it was still a fairly large, bulky engine, both in block height and width. A Cosworth was more compact. (photo HG)

Pictures of the Foyt Chevy V6 seem to be a rarity. Even in the AJ Foyt media guide booklets this was the only picture (found in the 1988 booklet) that shows some part of the engine. The man in the center is Howard Gilbert.

All of this makes me come to the conclusion that the Chevy V6 was definitely an engine with potential. Its speed in both practice and qualifying tells that story. To put the 1990 speed of 212+ with the 1986-vintage 86C in some more perspective: had anybody driven the car in qualifying and averaged that speed in his qualifying attempt he would have qualified for the race. But the engine had the wrong name on the valve heads, lacked the decent support from committed engineers and engineering companies and was instead looked after by someone distracted by too many other priorities and no longer in a position to take on a project like this and make it succeed.

Hadn't it been for the Ilmor-Chevy and to some extent the Buick V6, and had there been more support than what AJ Foyt Enterprises was able to come with, it could have been an entirely different story. If this engine had had a Chrysler background, or even Ford Motor Company heritage (Ford was still kind of represented in CART racing but the DFX was about to be overthrown by the Ilmor/Chevy) its chances of obtaining factory support could have been better as well.

So back to the Buicks. Apart from their terrible reliability compared to the quadcam V8s, another problem was that the V6 had a higher center of gravity, upsetting the balance of the cars they were fitted in. Between 1984 and 1986 the Buicks were used in the latest type of March chassis but since then the majority were generally found in cars of at least one year old, primarily Lolas, cars designed for quadcam purebreds. As mentioned earlier, Foyt used his Chevy V6 'Blowtorch' in a March 86C as late as 1990. March really lost its edge in CART from 1987 and pretty much went out of the customer-car business in 1989. That is why March was hardly involved in the increasing popularity and development of the latest stock blocks.

Using elderly (’87-type T87) Lolas in 1988 and 1989 instead of the latest models wasn't such a big handicap as it would appear at first sight as the performance-level gap between the T87/00 and T88/00 was't that big. It says enough about the year-old car's competitiveness when you consider that Lola importer Carl Haas provided a T87/00 to his own driver Mario Andretti in 1988. Other than Rick Mears in his Penske-Ilmor, Mario was the only driver to break the 220mph barrier during practice that month. Not a single 1988-built Lola managed to equal that feat…

In defence of the 1988 Lolas it must be said that no single example was Ilmor-Chevy-powered. To prove that Ilmor-Chevy power made a difference, there were only two March-Chevy 88Cs in the field. These two were the fastest 88Cs - and Marches for that matter.

Back to the Buick V6 again, it was a bit heavier then the racing quadcam V8s but several drivers liked the engine quite a bit because it had more torque.

In 1989 Jim Crawford was the sentimental favourite to many after his performance the year before. He was quick in practice, qualified fourth fastest only to wreck his car seriously. It was so bad that the tub (a two-year old T87/00) had to be sent back to England for repairs in order for Jim to retain his qualifying position and avoid starting in 33rd with the back-up. The car was finished in time but Jim couldn’t impress like he had the year before.

The 1989 race was rather bizarre with leader Fittipaldi having a gigantic lead over the majority of the field. Only Al Unser Jr eventually ended up on the same lap but everyone else was at least three or more laps down. In the duel for the lead Unser crashed out on his 199th lap but was still classified second. Scott Brayton finished the race classified sixth (also his qualifying position) with 193 laps. This was one of the Buick V6's best-ever performances up until the time.

The promo shot of the Buick V6 as found in the 1989 press kit.

A high-water mark for the Buicks came in 1990 when they powered one third of the field, but its highest finisher (Didier Theys in a Granatelli-entered PC18 that covered 190 laps) came home 11th…

But in all fairness it must be mentioned that none of the Buicks was built into a brand new chassis. Due to new rules valid from 1990 cars of one and/or more years of age stood no chance against the 1990 cars, with the exception of the March-Alfa Romeo 90CA. Now, using a 1990 chassis was unlikely to have had any beneficial influence on the reliability issue. But better practice and qualifying speeds would have been possible.

The picture of the 1990 Buick V6 as found in that year's press kit.

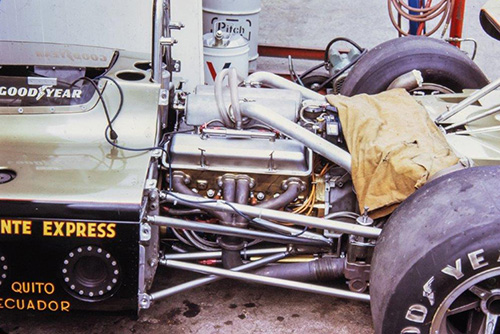

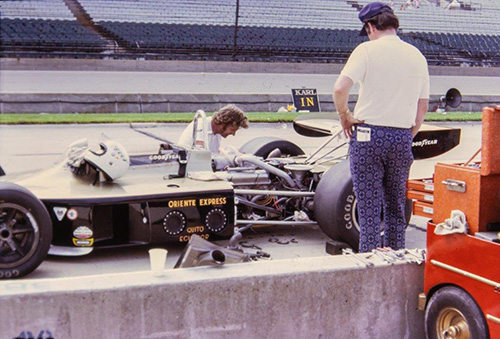

Roger Penske sold off some of his 1988 and 1989 cars, but without the Chevy engine for which they were designed. A few of them got a Cosworth but Vince Granatelli, among others, fitted them with Buicks. Here is the installation of a Buick in a Granatelli-run 1989 Penske as seen in 1990. Note that the entry into the plenum is off-center. (photo HG)

Jim Crawford in the car he raced in 1990, a 1989 Lola-Buick. This was his back-up car. The primary car was lost on May 11 ('Fast Friday') in a monumental Turn One crash that lifted Crawford’s car some six feet into the air before it landed on its belly again. Crawford had lived up to the old wisdom again: If you can’t win, be spectacular! (photo HG)

Buick and the most prominent Buick runners finally realized it was time to take on the quadcam brigade on equal terms in the chassis department too. To be successful the Buick teams needed brand new cars, if possible, adopted to the characteristics of the Buick engines. Buick and its primary allies raised their game.

How the genie was bottled and corked

Buick took up the challenge to the purebred racing quadcams seriously in 1991, so they started a genuine factory-supported program still using their production-based V6. The blocks in particular were still very much like the genuine production versions, with castings made out of steel, although excess material was removed as much as possible. Compared to the engine of the year before, the 1991 version was some 25 pounds lighter.

One company involved with the development of the Buick was Brayton Engineering, owned by the father of driver Scott Brayton. Scott remained loyal to the Buicks between 1985 and 1989 but in 1990 he switched to a Cosworth and in 1991 his team owner Dick Simon got him a Chevy engine. No way you stuck with a Buick if you could get a Chevy!

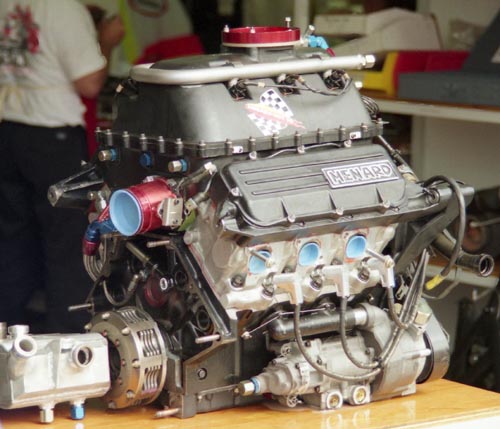

Brand new Lola cars designed for use with the V6 were commissioned by the teams of Kenny Bernstein and John Menard. Several other team owners also obtained these bespoke Lolas. The Lola they got was the T91/01 and they had slight design modifications to cope with the characteristics of the engine in both practical use as well as construction. Weight and weight distribution were different for the V6 compared to that of the V8s. In order to compensate the Buick-powered T91/01 had its front and rear suspension moved rearwards so the GC went to the center of the car. Another first for the T91/01 was that, unlike with the older cars, the V6 was used as a stressed member of the chassis.

These bespoke Lolas were tough to deal with for the quadcam opposition, both in practice and qualifying. Pole Day 1991 became a waiting game for the best time to get out on the track (5-6 pm) but a sudden downpoor prevented some hotshoes to qualify on Pole Day. The following day it was Team Menard driver Gary Bettenhausen in a Lola-Buick T91/01 who became the fastest qualifier of the field.

In the race however, the Buicks were no match for the Chevies: There were ten Buick-powered starters but only two of them made it into the upper half of the final classification and only one of them into the top 10.

An example of the bespoke Lola-Buick T91/01s. This is the one driven by Gary Bettenhausen, the fastest combination in qualifying that year. This was the first year that Team Menard used fluorescent color schemes. The yellow in this scheme made it a pain to the eye to watch in bright sunny conditions. (photo HG)

There was, however, much more going on in 1991 that would have dire consequences and these will be discussed elsewhere.

In addition to that, USAC still wasn’t satisfied about how the turbocharged stock blocks performed on Race Day and decided to improve their chances. Despite having some 100 or so more hp, the production based engines were still no match for the purebred racing engines. To make an engine based on a design for a, say, 300hp-at-best road car produce up to 850hp put quite a strain on reliability and the finish record of the Buicks was a testimony to their fragility.

USAC also wanted to make the '500' more appealing to smaller engine-building companies with expertise in stock-block technology. In order to achieve this idea that was heavily promoted by USAC official Roger McCluskey (the same Roger McCluskey who once drove the turbocharged AMC stock block in the seventies) USAC decided during 1991 to grant the same capacity and turbo-boost advantage to newly designed engines with pushrod technology and two valves per cylinder.

The rule in question, Clause 115-D, read as follows:

“Turbocharged four-cycle single non-overhead camshaft (camshaft in block) engines with pushrod operated valve mechanisms, two valves per cylinder, will be limited to a maximum piston displacement of 209.3 cubic inches (3430cc) and a maximum of eight cylinders.”

Clause 118-B stipulated that the maximum allowable boost for this type of engine was set at 55 Inch, while Clause 118-D prescribed USAC's rights to alter the manifold pressure for any event.

In hindsight, USAC had now created a situation that could have large consequences. They had caught a genie and bottled it up. Initially, nothing of any true importance happened with respect to this rule change. But Buick continuing their project at the level they brought it to in 1991 made people look at the rule more seriously later on.

John Menard and King Motorsport continued their efforts in 1992 and again ordered bespoke Lolas for the Buick V6. These cars were absolutely the fastest cars in practice and only the near predictable unpredictability of the Buicks made that just two of the four fastest Buicks made it onto the first two rows. But Roberto Guerrero, driving for King Motorsports, won the pole by a large margin. Long-time Buick driver Scott Brayton who got a Chevy deal in 1991 and whose primary car was Chevy-powered, switched back to a Buick again in what appeared to be the most competitive year for the V6 ever. The Chevy engines (/A for everyone else, /B for Team Penske) were left eating dust in practice as well as qualifying. Only the brand new, ultra-compact Ford Cosworth XB was capable of challenging the fastest Buicks. All four XB-powered cars filled out the two front rows with the two fastest Buicks.

However, due to the unusual weather conditions on Race Day, pole sitter Guerrero spun off during the warm-up laps. The only Buick-powered driver who was a remote factor that day and acquitted himself admirably was Al Unser Sr. He eventually finished third and was the first driver to make a Buick V6 go the full distance. It was the best result for the Buick up to that moment.

While 1992 had at least shown some promise and signs of tremendous progress, the Buicks were unable to continue their progress in 1993. One of the reasons of their limited success in ’93 was that Buick had given up on the program. Their engine was still an `Indy only` engine since CART refused to permit stock blocks running with the same boost advantage as USAC gave them at Indy. Instead, CART forced the stocks to run on 45 Inch boost, just like the quadcams. This made the Buicks a waste of effort during the other CART events. In a statement released on September 30, 1992 Buick gave up on the V6 since the engine had become “more specialized and moved farther away from the nature of the production engine.”

Lee Brayton and Jim Wright took over the project, funded by John Menard. The Buick-based engines (now called Menards) were developed for Team Menard’s Indianapolis program. One of the main motivations for Menard to keep the Buick program going was the engine's heritage: American. Patriotism was an important factor in Menard’s engine program.

This is what a 1993 version of the Menard-supported Buick looked like. (photo HG)

Menard had again ordered new Lolas for his program but this time it didn’t help. But there were other reasons why they made less of an impression in ‘93. We’ll talk about that somewhere else.

My favourite of the Menard Lolas - colour-wise at least - entered in 1993, Geoff Brabham’s #27. This is a 1993-built Lola chassis adapted to the Buick V6, also built according the new 1993 rules mandating longer noses and generating less aerodynamic downforce. Since 1991 the Menard entries always carried bright fluorescent colours. This was definitely one of the most attractive colour schemes of all Menards “Pain to the Eyes Specials”. (photo HG)

American engine manufacturers didn't seem that interested in building purebred racing engines. The Chevrolet-branded Ilmor was built in England, and so were the Ford Cosworths and Judds. So in order to have some Genuine American Engine Technology on its grid USAC had to put its faith into the pushrod technology and the engineering companies and hotrodders that trusted such engines.

The final verdict about the stock blocks at Indianapolis one could make in 1993? At the end of 1993 it would still remain tricky to make a definitive conclusion about the value of stock blocks at Indianapolis. Focusing on their success in terms of race results, one would say their influence was limited. Before World War II however, they can be credited for enabling a number of drivers to race on in the difficult years of the depression.

After the war, there were several attempts to enable production-based engines to compete against purebred racing engines. But it never really worked.

From 1985 on, when the Buick V6 appeared on the scene, this engine obtained a certain popularity. This was partly influenced by the fact that it became increasingly more difficult to obtain competitive quadcam racing engines, especially for the smaller teams due to the costs of such engines. When the Ilmor-Chevy V8 became the engine of choice but remained in too short supply to fulfil the demands the Buick became an even more viable option. Reliability remained an issue but the Cosworth was left without a chance against the Chevy, so an alternative became necessary. This was to the benefit of the Buick. One could say that the popularity of the Buick increased because of the politics surrounding the Chevy.

But what happened in the races was really quite predictable. From the outset, the Buick V6 was never designed as a racing engine, so it was required to perform at a level never demanded from the basic design. Modifications helped but came up short.

So in all honesty, the best the Buick achieved and can be credited for is that it filled a gap left by the insufficient numbers of Chevy V8 engines. It was the lifeline for a number of smaller teams, enabling them to compete in the 500-miles race. For this fact alone, the Buick deserved better results than the two poles and the third place it achieved up to 1993. Buick and the people who worked on the engine in the years up to 1993 deserve to be credited for having done so much to allow teams to participate at Indianapolis, a fact largely overlooked because of a lack of decent results.

Two poles and a third: these were the three most rewarding results obtained by the Buicks. Ironically the Buick V6 matched the results obtained by the Novi V8 which in its day, like the Buick, was the most powerful engine used at the Speedway!

One of the Novi's poles, however, wasn't set with the fastest qualifying time. On the other hand, a Novi driver was fastest qualifier while not being on pole on no less than five occasions, a feat the Buick drivers achieved only once…

Despite its fairly limited success on Race Day, the Buick's surplus of power was still the envy of some team owners. But the V6 remained too much of a compromise. Certain people were looking at the 'clean-sheet-of-paper pushrod' option by now. Some of the compromises in the Buick could be avoided by a purpose-design engine. Such an engine was to be an entire different animal to deal with.

Someone was not to see the results of his brainchild. Late 1993, Roger McCluskey, the man who so much promoted the creation of purpose-design pushrod engines died after a period of serious illness. Which leaves me wondering. Would Roger McCluskey still have been in favour of the suggestion he promoted if he had had any advance knowledge and realized what kind of Pandora's box his train of thought would open?

Addition made in September 2014: In his book Beast, Jade Gurss provided information that the rulemaking situation with respect to the pushrod engines was slightly different, with other factors not mentioned here being involved. I refer to the addendum added to Part 22 for more details about this situation.

Addendum

In order to indicate the progress made by the Buick V6, here is a listing of the 1985 and 1992 engines as found elsewhere on the Internet.

| 1985 Buick Indy V6 | 1992 Buick Indy V6 |

| 209 CID turbocharged @ 57" Hg abs, methanol | Configuration: 90-Degree V-6; even firing, two valves/cylinder |

| Buick Stage II iron case | Boost: 55 inches mercury (USAC); 50 inches mercury (CART) |

| 3.80" bore x 3.06" stroke | BHP @ RPM: 785 at 9200/USAC; 720 at 9200/CART |

| 9.25:1 CR | Rev. Limit: 9200 rmp |

| 40cc chamber, .040" gasket | Torque @ RPM: 490 at 7500 |

| 1.485" comp. height | Engine Bearings: Vandervell |

| 9.56" deck height | Displacement: 3.4-liters (209 C.I.D.) |

| 6.5" rod | Ignition: Buick Heavy Duty Power Source |

| Buick Stage II cylinder head, modified | Fuel System: Buick electronic fuel injection |

| 230 cc intake port, 1.60"h x 1.48"w | Bore: 3.900 inches |

| 2.08" dia. Intake valve, Ti | Stroke: 2.900 inches |

| [20.38 sq in total intake valve area] | Cylinder Heads: Buick Stage II aluminum |

| 1.60" dia. exhaust valve, Inconel | Valve Lifters: Roller-type |

| [12.06" sq in total exhaust valve area] | Crankshaft: Buick: forged, even firing |

| 108 degree lobe separation | Block: Buick Stage II; cast-iron 40 bolt mains |

| 276 degrees int/exh duration @.050" | Fuel: Methanol |

| Int/Exh lift at lobe .400" | Compression Ratio: 10:5 |

| .655" net valve lift | Intake Valves: Titanium, 2.08 diameter |

| Intake lobe center in @ 107 degrees | Exhaust Valves: Inconel, 1.60 diameter |

| On the dyno [corrected to 60F at 29.92" Hg] this deal made: | Connecting Rods: Forged steel, 5.500 inch |

| 802 bhp @ 8400 rpm | Pistons: Forged Aluminum |

| 540 lb ft @ 6000 rpm | Oil Pressure: 100 P.S.I |

| Oil System: Dry sump | |

| Push Rods: Tubular, 8.900 inch | |

| Camshaft: Hardened steel | |

| Turbocharger: Garrett |